Here’s the thing about campaigns that any political pro will tell you: They are unpredictable. Crunch all the data you can get your hands on. Look at historical voting patterns. Talk to the smartest electoral minds around. There is still a human element and humans, by their nature, are never entirely predictable.

The rise and resilience of Republican nominee Donald Trump are the greatest proof of this offered by the 2016 United States presidential campaign. Yet, as unforeseen events go, the growing furore over Trump’s treatment of Khizr and Ghazala Khan is still remarkable.

For those who may have missed it, the Khans are immigrants from Pakistan. Their son Humayun, who was born in the UAE, was only a toddler when the family arrived in the US. He joined the US army after graduating from university and died in 2004, the victim of a suicide bombing while serving in Iraq.

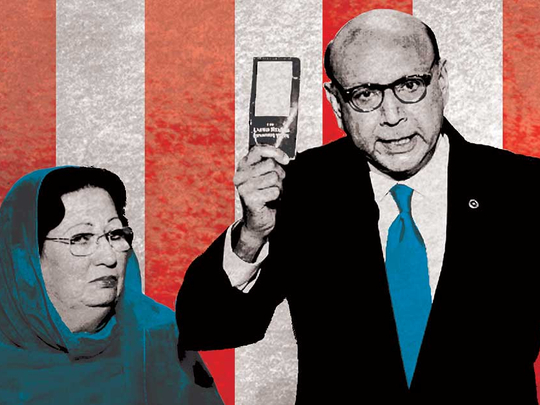

Khizr’s brief speech last week on the final night of the Democratic National Convention hit America with an emotional force that one suspects took even Hillary Clinton’s campaign by surprise. With his wife standing silently beside him Khan told the story of their son’s life and death, scolded Trump for his attacks on immigrants and Islam and told the reality-TV-star-turned-politician “you have sacrificed nothing and no one”.

Any sensible politician in Trump’s position would recognise the Khans’ criticisms as a no-win proposition and would have said nothing. When the inevitable question from an interviewer came he would have expressed sympathy for the bereaved parents, praised the dead soldier and changed the subject. Instead, Trump implied that Ghazala had let her husband deliver the entire speech because either he or Islam or both prevented her from speaking (a claim she rejected in several televised interviews over the days that followed) and lashed out at Khizr repeatedly on Twitter and in an interview with ABC News.

During that interview, Trump dug himself into an even deeper hole with the utterly nonsensical claim that his business success counts as sacrifice on the country’s behalf. “I’ve made a lot of sacrifices. I work very, very hard. I’ve created thousands and thousands of jobs, tens of thousands of jobs, built great structures,” he said.

By next week, all of this may be forgotten, but something about Trump’s clash with the Khan family feels different. It is not just that the Khans are about as sympathetic a couple as anyone can imagine. Or that few things are less socially acceptable in current-day America than showing disrespect towards the families of fallen soldiers.

What the Khans have done is put a human face on Trump’s proposed ban on immigration by Muslims — a face that only becomes more human and more sympathetic when Trump and his spokespeople answer questions about the Khan family’s sacrifice by talking about “radical Islamic terrorism”, as they did repeatedly in interviews on Sunday morning.

More than anything else, though, it is timing that has given this controversy such unique resonance.

Among politicians, the most damaging revelations are those that reinforce the doubts a voter already harbours. This is why the controversy over Hillary’s email server never quite goes away: It reminds people — even supporters — that for all her appeal she is prone to legalistic dissembling and often seems to think that the rules everyone else has to follow don’t apply to her.

For four days last week, the refrain from one Democrat after another was that Trump is a racist, a bigot and a misogynist; that he thrives on division, seeks to pit Americans against one another and that, as a result, he is temperamentally unfit for the presidency. As Hillary said in what was arguably the most memorable line of her acceptance speech: “A man you can bait with a tweet is not a man we can trust with nuclear weapons.” Trump’s attacks on the Khans validated all these criticisms in a clear and simple-to-grasp way at a moment when the Democrats’ indictment was fresh in the entire country’s mind.

The Khans’ speech was not, by any measure, the centrepiece of the convention’s final evening. There was little or no on-air promotion of it before the fact. Among cable channels Fox News did not air it and it came at a time of the evening when the broadcast networks (which have far larger audiences) were not covering the convention at all.

Yet, something about the Khans resonated in ways no one could have predicted. In a convention marked by excellent speeches and centred around a historic nomination, the Khans’ brief appearance captured America’s attention in a way nothing else last week did.

Of course, November is still a long way off. And Trump has proven that he can weather storms that would sink any ordinary politician. But the last week has been a reminder that campaigns can take dramatic and abrupt turns and that the bigotry Trump pedals may not have as large an audience as it sometimes seems.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches Political Science at the University of Vermont.