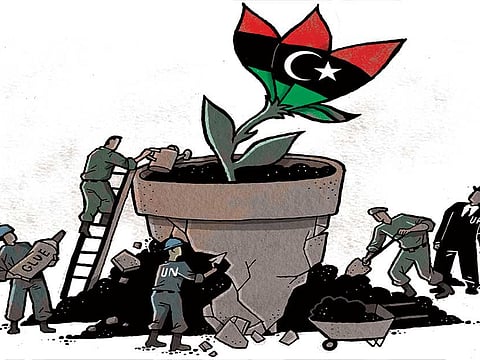

Libya’s allies must join to unite the country

If the world can speak as one and stand behind the UN plan, this country can be great again

I was standing on the hot Tripoli dock with the head of the Libyan coastguard, when he gestured at what has been for the past six years the most abject eyesore of the harbour. “Look what you did, you British!” he said. This Libyan coastguard has a serious shortage of ships. Every week, he and his men are out at sea, chasing down people smugglers. Every week, those loathsome human flesh-traffickers are at it again, cynically pushing people onto the waves in home-made dinghies. It was only a couple of months ago that a furious row broke out: Between the Libyan coastguard and the charities employing mercy ships to pluck people from the sea. The Libyans said the charity boats were acting as magnets for the migrants. The NGOs said the Libyans were recklessly preventing their rescue operation. All sides agreed on one thing — that the Libyan navy was struggling to cope. Tripoli’s coastguard has only three elderly vessels. There in the water was a reminder of what the Libyans once had: A great big frigate. And there, splat in the middle of its heeled-over hull, was a calling card from the Royal Air Force — a socking great exit wound from a missile. Yes, you will find plenty of people who will be happy to describe that twisted shipwreck as a metaphor for Britain’s contribution to recent Libyan history. They will observe that in 2011, Britain glibly co-operated with France and the United States to remove the dictator, Muammar Gaddafi. And then, they say, the western powers walked whistling away — leaving the Libyans holed beneath the waterline. In Libya, today, there are three guns for every human — but there is no single source of law or authority, let alone power. There are two central banks, two rival parliaments, three prime ministers and up to four governments. And, of course, there are umpteen militias vying with the Libyan National Army for control of the vast and lawless beige spaces on the map. And in those lawless territories we are seeing the breeding-grounds of terrorists and people smugglers — the criminals whose activities have had such an impact on western Europe. You can see why some Libyans are tempted to blame the West for their current predicament, and even to hanker for the days of Gaddafi. And yet there are plenty more who think otherwise. Most sensible Libyans are profoundly glad they are no longer tyrannised by a man who tortured, jailed and murdered thousands. Many young Libyans are still grateful for the role the United Kingdom played in Gaddafi’s removal. And they can also see that the UK is there for them today, committed to the long-term success of the country and determined to help a new democracy to be born. We are there for the Libyan coastguard, with the Royal Marines providing them with training. We are teaching them the law of the sea. We are teaching them English and how to communicate with a terrified migrant from Nigeria. In the past few days, the UK government has pledged funding for de-mining operations and new clinics, and rebuilding critical infrastructure in Sirte, from where Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) has finally been driven. I have seen much of this in action. Though some of it makes one tingle with pride, we all know the reality: That these measures are merely sticking plasters over the great gaping wound in Libyan society. Unless and until Libya has a functioning and unifying government, Libyans will continue to suffer grievously. Without a political solution, the country will still be the front line — our front line — in the struggle against illegal migration and terror. The signs of hope are there. Tripoli is getting safer. I was the first British minister to be able to visit Misrata since the revolution of 2011. A deal is there to be done: Gluing back together the east and the west, uniting the internationally recognised, but severely limited Tripoli government with the supporters of Benghazi’s General Khalifa Haftar, who controls so much of the country. All it will take is a bit of maturity and patience by the Libyans and, above all, a joint approach from the international community. Now is the time for all the friends of Libya to lay aside their differences and get behind the work of the excellent new United Nations Special Representative Gassan Salame. As I bank over the extraordinary ruins of Leptis Magna, I am reminded that this was once a cultural and commercial jewel of the Mediterranean world. If the world can speak as one and unite behind the UN plan, Libya can be great again.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

Boris Johnson is the British Foreign Secretary.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox