The Democratic presidential race is entering a decisive period with candidates holding their much anticipated first debate on Tuesday in Las Vegas. Key international issues, from the Middle East to climate change and free trade, will be at the centre of discussion, with frontrunner Hillary Clinton likely to come under heavy fire from her principal declared opponent, the socialist Senator Bernie Sanders.

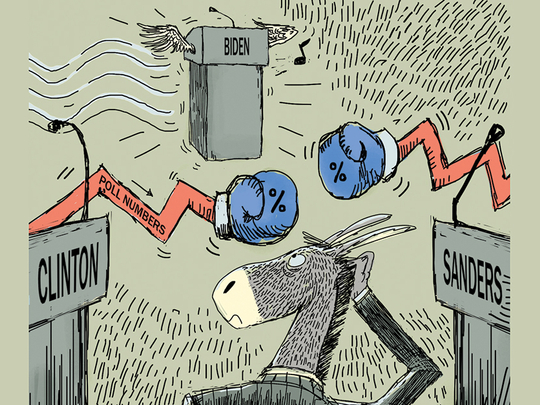

With Clinton’s previously sky-high poll numbers softening, there are growing signs of her concern about the left-wing challenge from Sanders, and also the possibility that Vice-President Joe Biden might enter the race. On Wednesday 7th, for instance, Clinton decided to come out against one of the central foreign policy achievements of President Barack Obama’s second term of office: the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal which was secured, subject to domestic legislative approvals, in negotiations last week by 12 nations in Asia-Pacific and the Americas which collectively account for some 40% of global GDP.

Clinton’s position on TPP, which is widely opposed by key Democratic Party constituencies such as organised labour and environmental lobby groups, is a significant u-turn given that she described it in 2012 as Obama’s secretary of state as the “gold standard in trade agreements to open free, transparent, fair trade”. Her new-found opposition to the pact reflects, in large part, her concern that supporting it will undermine her prospects of winning the Democratic president nomination in 2016: in her 2008 campaign she, ironically, took heavy criticism from then-Senator Obama over her support for the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) agreed during her husband’s presidency.

Sanders, who is highly critical of many of Clinton’s relatively hawkish foreign policy views, including her original support for the 2003 Iraq War, and the subsequent 2011 military intervention in Libya, has described the TPP deal as “largely written by Wall Street and corporate America”. He is making opposition to the trade pact a key platform of his campaign “to stop letting multinational corporations rig the system to pad their profits at our expense”.

While Clinton remains the frontrunner to win the Democratic crown, her poll numbers have softened following concerns over her handling of controversies over her personal email use when she was secretary of state between 2009 and 2013. On the horizon, moreover, are congressional hearings on October 22 where she will give testimony, in the face of potentially hostile questioning, over the 2012 attacks on a US diplomatic outpost and a CIA annex in Benghazi, Libya, for which she has been attacked by Republicans.

The decline in Clinton’s poll numbers is underlined by the latest Reuters/ Ipsos poll taken from October 4 to October 9 which shows her falling from 51% of Democratic supporters to some 41 per cent. Meanwhile, support for Sanders rose to 28% and for Biden (despite the fact he may not join the contest) to 20 per cent during the same period.

Support remains very low in polls for the remaining declared candidates: former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley, former Virginia Senator Jim Webb, and former Governor of Rhode Island Lincoln Chafee. However, the Las Vegas debate offers a major televised opportunity for them to raise profiles.

While it is still unlikely that Sanders can win the nomination, the success of his candidacy is pulling Clinton to the left. This is underlined not just by her new stance on TPP, but also her opposition announced on September 22 to the Keystone oil pipeline from the United States to Canada, which she was involved in negotiating as secretary of state, but now opposes. Sanders vehemently opposes the pipeline which has become a focal point of opposition of liberal voters and environmentalists, partly because of its regressive impact on global warming.

Of potentially bigger danger to Clinton’s campaign is Biden who is contemplating jumping into the race. His entry would energise the Democratic competition in a way no other candidate, except perhaps Senator Elizabeth Warren, could achieve.

Biden has the experience and appeal to make a very strong candidate, after standing previously in 1988 and 2008. In part, this is because of the respect he has garnered as vice president where he has assumed a significant role on both domestic and foreign policy.

This reflects both Biden’s high standing with Obama, and also the fact that the office of the vice president has assumed more power in US administrations in recent years. This is underlined by larger staff budgets, greater proximity to the centre of power through a West Wing office in the White House, weekly one-on-one meetings with the president, and authority to attend all presidential meetings.

Biden, who could make a decision within days, also has the weight of history behind him if he makes a third White House run. That is, the vice presidency has become perhaps the single most common pathway to trying to assume office of the presidency in the post-war era.

Since 1960, four US vice presidents — Richard Nixon in 1960, Hubert Humphrey in 1968, Walter Mondale in 1984, and Al Gore in 2000 -- won their respective party’s presidential nomination but then lost the general election, while two (Nixon in 1968 and George HW Bush in 1988) were elected president. Moreover, Lyndon Johnson and Gerald Ford became president after an assassination and a resignation, respectively.

One reason vice presidents enjoy such success in securing their party’s presidential nomination relates to the 22nd Amendment of the US Constitution. This amendment, ratified in 1951, restricts presidents from serving more than two four-year terms. Importantly, this allows vice presidents the possibility of organising a presidential campaign in the sitting president’s second term without charges -- from inside or outside the party — of disloyalty.

Taken overall, Clinton remains the favourite, despite the threat from Sanders, and the possibility Biden could jump into the race. Nonetheless, her potential emergence as the Democratic nominee is no longer as assured as once seemed likely, and she is being pulled to the left on key issues which could undermine her prospects for victory in the 2016 general election against Republicans.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.