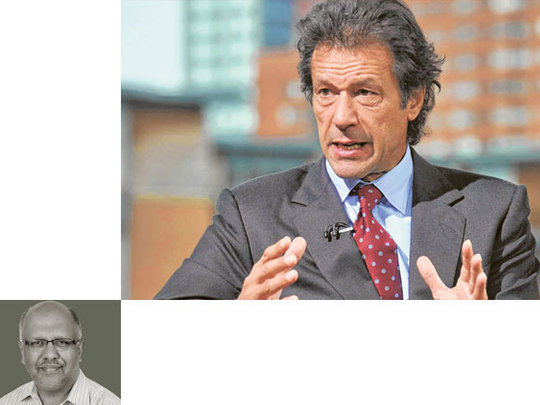

When Imran Khan, Pakistan’s cricket star-turned-politician, ventures into Pakistan’s tribal areas today to demand an end to US drone strikes on the country’s territory bordering Afghanistan, he will surely be making history.

For years, Imran has been the lone voice among Pakistani politicians, campaigning for an end to controversial drone attacks carried out by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The CIA’s rationale behind such attacks is squarely that of targeting a region which the US claims has become a hotbed of militants who have routinely attacked western troops in Afghanistan.

Yet, over time, evidence has piled up suggesting that many of the casualties in these attacks are innocent civilians, including women and children, who are just caught in the cross-fire.

While some of these attacks may have targeted militants, the presence of an overwhelmingly large number of innocent people among the victims only raises profound questions over the legitimacy of using drones.

Though considered a potent weapon in military terms, involving no risk to human life among western military troops, given the pilot-less character of drones, they have indeed created a far bigger risk to prospects of stability than what is measurable in statistical terms.

In less than two years from now, the US-led western military alliance deployed in Afghanistan will reach its deadline of withdrawing troops from Afghanistan. Between now and then, if indeed the withdrawal proceeds on schedule, thousands of western troops along with their military hardware, which by some estimates could be worth approximately $60 billion (Dh220.68 billion), will leave the perils of conflict-ridden Afghanistan.

Yet, what will surely stay behind will be the legacies from the past 11 years since a US-led campaign was launched on Afghanistan, following the terror attacks on New York on September 11, 2001. Among those legacies, drones and the destruction they have caused will be remembered for years to come.

While difficult to measure in statistical terms, the anger that has been triggered with these attacks will not end with the withdrawal of western troops, even if a peace formula between the key combatants is finally reached in Afghanistan.

The record from the attacks in Pakistan’s tribal areas bordering Afghanistan clearly suggests that the policy has become increasingly controversial over time. Across Pakistan, where anti-US sentiment has grown over time, the matter of drones has become central to the criticism of Washington’s policies.

While Imran’s campaign by his own admission seeks to press the case on moral grounds, there is no strong political dimension to this case. Imran has indeed become Pakistan’s first mainstream politician to have ventured towards a frontier region that is widely considered to be unsafe beyond the challenges which surround other parts of the country.

Imran’s gesture stands in sharp contrast to a leader like President Asif Ali Zardari, who has not ventured into the frontier region bordering Afghanistan during his four-year presidency. Zardari’s refusal to step in to a region that is central to Pakistan’s ongoing campaign against militants has only reinforced his character as a “bunker leader”, who is simply unable to lead his country from the front.

Going forward, Imran’s example now raises the challenge for other Pakistani leaders to follow suit. Though Imran’s demonstration today in itself may not force the US to end its drone campaign, it at least sets a strong precedent, recording a public protest by Pakistanis to the use of what is clearly a controversial military tactic.

There is indeed also a strong global dimension to the use of drones in Pakistan. Elsewhere too, such as in Yemen, the CIA has begun employing a similar tactic disregarding their controversial character. The mere possibility, no matter how remote, of innocent deaths caught in the cross-fire must force a review of a tactic that may be successful militarily, but defeats the very objective of consolidating a military gain.

An ultimate assessment, if made just on the strength of body counts, will surely just miss out the wider point raised. A recent study released by Stanford University in the US raised some compelling questions pointing towards the imperfect nature of the gains from carrying out repeated drone attacks. More than a decade after the New York terrorist attacks triggered a US-led global military belligerence in the name of fighting terror, evidence such as the findings of the Stanford University report must lead to a fundamental shift in global policies on tackling security challenges.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.