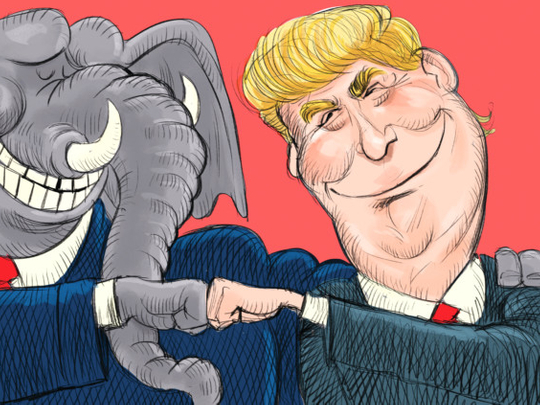

A common refrain among American politicians and pundits is that if he wins the Republican Party’s presidential nomination, Donald Trump will tear the party apart, possibly irreparably. I am here today, however, to offer a cautionary note: If, as seems increasingly likely, Trump is the nominee, do not be surprised to see the party rally around him: Some actively, many more passively.

This is not to say that Trump is destined to win November’s general election in the United States (though he might — and, yes, I used this space last year to say such a thought was impossible. Clearly, I was very wrong about that). Rather, my point is that even if, come October, the real-estate-developer-turned-reality-TV-star is clearly headed for a crushing defeat, it will likely be with more of the GOP supporting him than not.

Many people are appalled by Trump and are dismayed by what his rise says about both the Republican Party and the country at large. Trump’s rhetoric and the occasional violence and general sense of menace that pervade his campaign rallies disturb many Americans at both ends of the political spectrum. Many people, however, are clearly not disturbed. The crowds that turn out to see Trump are large and enthusiastic.

Before Tuesday’s primaries in Florida, Ohio, Illinois, Missouri and North Carolina, about 12.4 million votes had been cast in Republican primaries and caucuses. Trump had won slightly more than 4.3 million of them — about 35 per cent. Even in a country of 320 million people that is a lot of votes — and when the results come in, only about half the country will have voted. Another three months of primaries then stretch out.

It is noteworthy that none of Trump’s remaining opponents have been willing to call him a racist (more interestingly, both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders also refused to use that term when asked about it at a debate last week). All three say they will support him if he is the nominee (though Florida Senator Marco Rubio has waffled a bit on this over the last few days).

This is how the quiet accommodation begins. In the coming months, a few high-profile Republicans will break with Trump, as 2012 GOP Presidential nominee Mitt Romney recently did. Some will embrace him — particularly those who sense that Trump is popular among their constituents. Almost any politician who sees supporting Trump as a matter of political survival will do so whatever their private feelings about the man may be.

The vast majority will simply hold their peace. In 1984, as a student journalist, I travelled to San Francisco to cover that year’s Democratic Convention. Ronald Reagan was running for reelection and the Democrats were about to nominate a candidate, former vice-president Walter Mondale, for whom many in the party lacked enthusiasm. More than 30 years later, I still vividly remember interviewing the governor of Georgia, a now-forgotten pol named Joe Frank Harris, who looked at my tape recorder as though it might bite him and politely but firmly refused to say anything remotely positive about the man his party was scheduled to nominate for president later that day.

Party goes on

The trick was that he would not say anything negative either. Convinced that the Democrats were about to make a huge mistake (an astute call: Mondale went on to lose 49 out of 50 states), Harris confined himself to platitudes and made it clear by his body language that he wished my tape recorder and I would just go away. He remained a loyal Democrat, but sensing (accurately) that a lot of his constituents preferred Reagan to Mondale he clearly planned to sit that election out and hope his party would make a better choice the next time around. Two years later, Harris was reelected governor of Georgia with more than 70 per cent of the vote.

So for every Republican congressman, senator, governor or party elder who rationalises his or her way to an endorsement of Trump, expect a dozen or more GOP leaders to take Harris’ route: The path of ‘wait and see.’ In the meantime, the Republican Party as an institution will go on.

More importantly, should Trump win, have no doubt that the party will adapt itself to him. Why wouldn’t it? For many people, one’s personal opinion of the president matters little when power and the perks of office are on the line.

For now, at least, all that is a long way off and the immediate point is much more basic: If you are hoping that the institutional Republican Party will cast Trump into the outer darkness, prepare to be disappointed. If he wins the nomination, few in the party will disown him.

That means that beating him in November’s general election will not be the sure thing for which Democrats yearn. The next eight months are likely to be a wild — and often very unpleasant — ride.

Gordon Robison, a long-time Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches Political Science at the University of Vermont.