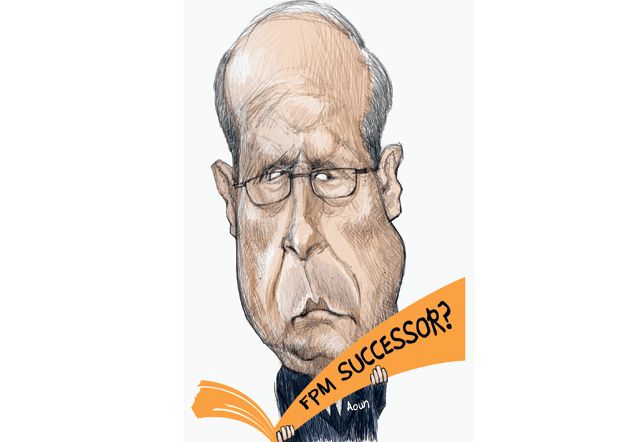

General Michel Aoun has always been a critic of bequeathing power from father to son in the complex world of Lebanese politics. He always took pride that, unlike Sa'ad Hariri, Walid Junblatt, Sulaiman Franjieh or Amin Gemayel, he built his political career single-handedly, without relying on a father, brother or grandfather for political legitimacy. He takes great pride that while Hariri is backed by Saudi Arabia and Hassan Nasrallah by Iran, the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM) is backed by a loyal constituency within Lebanon, not by a heavyweight in the neighbourhood. Things have seemingly started to change for the 75-year-old general, however, as he begins to worry about who will succeed him as head of the FPM.

Aoun famously has three daughters and no sons, and therefore nobody to carry his name. That is why, in recent years, he has put tremendous effort into grooming his son-in-law Gibran Bassil, 39, and polishing his image, often at the expense of old-time comrades in the FPM who have supported him for nearly 20 years. Bassil, after all, is not an exceptional politician — he doesn't have the brains of Fouad Siniora, the charisma of Nasrallah or the wealth of Sa'ad Hariri. Additionally, he has minimal political experience and failed to win a parliamentary seat during the elections in June. Aoun insisted, however, that Bassil be appointed minister despite a storm of objection — making it a condition for him joining the Hariri Cabinet. Aoun eventually got his way and his son-in-law was made minister of energy.

As if that favouritism was not enough, Aoun went one step further and made allies of the FPM, rather than ranking members, ministers in the new government. Fadi Abboud, for example, was made minister of industry, while Charbel Nahhas took what has been described as a "super portfolio", the Ministry of Tele-communications.

Veterans in the FPM, such as Aoun's right-hand-man Issam Abu Gamra, 72, began grumbling out loud, questioning Aoun's appointments and claiming that ranking members of the party are more entitled to Cabinet posts. There are two possible explanations for Aoun's strange behaviour. One is that Aoun wants to pave the way for Bassil's future leadership of the FPM. Another is that many ranking members of the FPM are not too pleased about Aoun's alliance with Hezbollah. Bassil may be the only FPM member who is willing and able to maintain that alliance in the post-Aoun era.

Tension

Abu Gamra's outburst is a sure sign that all is not well within the FPM. Abu Gamra, who served as Aoun's deputy prime minister in 1988, and held critical portfolios such as economy, agriculture and justice, described his boss's policies as a "mistake." He was particularly upset that ministers had been named from outside the FPM, insisting that this was not personal. According to sources in Beirut, he has objected to the ministerial appointments in writing, calling for the central committee of the FPM to be convened to discuss the matter. His call, to date, has fallen on deaf ears.

Sources close to Aoun, although careful not to criticise Abu Gamra in public, claim that he is furious at being nominated by Aoun for the Ashrafiyeh district, which was a losing bet from day one. What worries them is not the internal divisions within the FPM, but the sharp rift within the Christian community itself. At a macro-level the community is divided between Aoun and Samir Gagea of the Lebanese Forces (LF). The LF is not willing to mend fences with the Syrians, unlike Aoun, who visited Damascus this year. The Lebanese Phalange is furious with Hariri for not consulting them before naming their man Salim Sayyegh as minister of social affairs. The Patriarchal See is unhappy with Aoun's alliance with Hezbollah. Although former president Gemayel tried to improve relations with Hariri, members of the party's central committee are angry, and so is Gemayel's son Sami, who is leading what some are describing as a "youth uprising" within the Phalange against old-timers like Amin Gemayel.

All options are now on the table. Abu Gamra might leave the FPM, greatly damaging Aoun's image among old-timers in the Christian community. Some in the Phalange have threatened to walk out on the Hariri Cabinet, while the rift between Aoun and Gagea seems likely to widen as they battle for leadership of Lebanese Christians. A younger generation, including Gibran Bassil and Sami Gemayel, is emerging from the shadow of the veterans, promising to change the way things are done in Christian Lebanon, each in a manner very different from the other. In theory, the Maronite community should be happy because its traditional leaders are all back on the domestic political stage after many years in exile. The reality, however, is very different — showing just how divided the Christians of Lebanon really are.

Sami Moubayed is editor-in-chief of Forward Magazine.