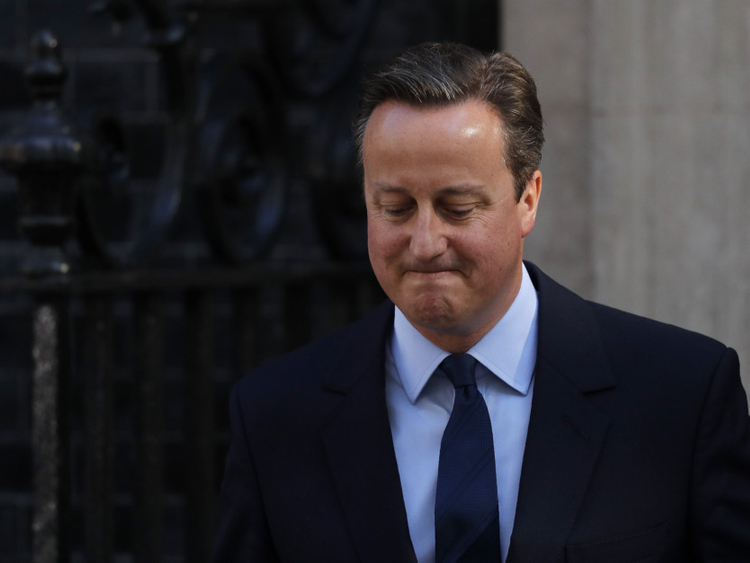

Enoch Powell’s famous remark that all political careers end in failure was never so apposite as in the case of David Cameron. Three months ago Cameron commanded British politics. He was expecting to be prime minister until 2019. It’s still a mere two months since he left No 10 after six years in the job.

Now he is heading for the exit from Westminster altogether, quitting as a backbench MP after initially promising to stay on until the next election. The air has gone out of his career with astonishing speed. And he’s not yet 50.

Ostensibly Cameron is quitting the Commons because he says it is hard for a former prime minister to be an effective MP for his Witney constituents. There is some truth in that. The constituency demands on MPs are far greater than they once were. It’s not so long ago that some Tory MPs only visited the constituency once every four or five years at election time. Nowadays an MP is a 365-days a year citizen’s advice worker, mediator and activist on behalf of tens of thousands of people who have instant access to his or her email address.

Yet as he prepares to write his memoirs for what is doubtless an extremely tidy sum, it’s unlikely that Cameron warms to the task of sorting out constituents’ complaints about welfare payments, the need for a Chipping Norton bypass, A&E closures and the rest. And as a new inductee into the rootless and roaming global elite of former political leaders, Cameron will already know that he has a choice between making a black-tie speech in Chicago for a six-figure sum and giving out the prizes at the annual Burford Conservative harvest festival.

Short-termist by nature

The bigger truth is that Cameron is going because he gambled his career and reputation on winning the European referendum — and lost. He lost because he has always been a short-termist and a tactical leader. He thought he could win the referendum on the back of his own communication skills and without building up the pro-European case in his party and in the country in his decade as leader of a largely anti-European party. The UK voted for Brexit because two out of three Tory voters voted to leave. Cameron was not strong enough to stop that from happening.

Just after the referendum, I had a brief private exchange with Cameron. He said it was very disappointing not to get the remain case over the line, as he put it. It was better to quit as prime minister, he added, because politics shouldn’t be about how long you stay out in the middle. Later I wondered whether Tony Blair, Gordon Brown or Margaret Thatcher would have used a self-deprecating cricket metaphor the way Cameron did. Almost certainly not. They would have talked about destiny, their cause and history. But that isn’t the Cameron way.

The prospect of sitting on the backbenches as Theresa May trashes much of his record probably holds very limited appeal for him, too. Although his initial commitment to stay on as an MP until 2020 raised the prospect of the former prime minister playing a significant role from the backbenches in the unfolding politics of Britain’s slide towards Brexit, it is hardly surprising that his heart is not now in it. May has already begun to redefine Cameron’s Toryism in dramatically new ways. Like Wotan in Wagner’s Ring, Cameron clearly judges that, once the spear that symbolises his power has been broken, it is time to slip away quickly and without fuss.

It’s a loss to public life — politics needs veterans, whether they are wise or silly. But it is hardly unexpected. Modern party leaders, whether prime ministers or opposition leaders, tend to leave the stage once the spell of their own power is broken. Perhaps to an extent they are the victims of their own hubris. But probably they are just plain knackered too. The disciplines of life in No 10 are ferocious as well as exciting, and once the rhythm is broken, the pace slackens, and audiences no longer hang on your every word, it is only human to want to make a clean break. It’s what most prime ministers of the modern age have done.

It all stands in striking contrast to an earlier time. William Gladstone was prime minister at 84. Churchill at 80. Among more recent premiers Jim Callaghan and Margaret Thatcher were well into their 60s by the time they lost power and left the Commons. Modern British politics still hasn’t found a useful place for the current crop of younger retired leaders, some of whom, like Blair and Cameron, leave Downing Street with at least 20 years of an average working life ahead of them. Perhaps Cameron will cope with retirement better than the ever restless Blair. It’s a fairly safe bet that he will.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Martin Kettle writes on British, European and American politics, as well as the media, law and music.