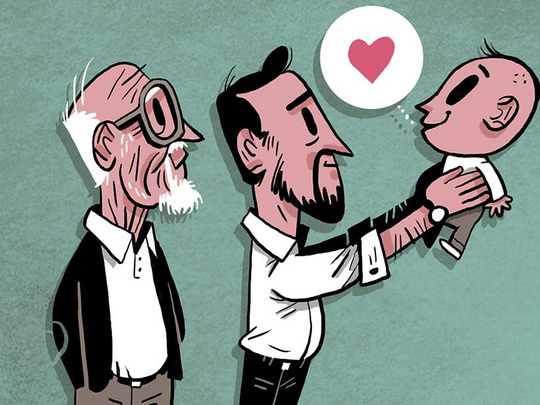

"I love you." Those three simple words messed me up for an entire week. I asked my wife if she heard them, too, or if I was hallucinating. I couldn’t believe the man in front of me said them. It wasn’t the message, but the messenger: my father. Who was this impostor? Could it be that this Pakistani-American immigrant, who grills halal lamb chops in boxers and sandals while listening to Sabri Brothers qawwali (music), had just said this to his almost-3-year-old grandson, Ebrahim?

I understand how fatherhood, and grandfatherhood, can profoundly change a man. The joyous burden forces some of us to adjust our career priorities, creates excessive anxiety for tiny people who don’t pay rent and inspires a lifelong goal of trying to become the only man in existence who looks cool driving a Toyota Sienna. But this sentiment from my father was a drastic disruption of a life I had always known.

In my 36 years of existence, my parents have never said “I love you” to me or vice versa. We are not an “I love you” family. Years ago, my mother told me “I love you” was for Amreekans and goras (white people), which at the time were synonymous, until they realised South Asians and other immigrants had every right to claim the American label as well. On Facebook, I recently asked if other children of immigrants, who are now parents, have witnessed a similar transformation. My old college friend Hooma Multani said some of us were used to a “Klingon-type way of displaying affection” and said her Pakistani father used to pat them on the back really hard instead of dispensing hugs and kisses.

“Unconditional love” for some of my immigrant-children friends was as mythical as wearing shoes in the house or talking back to elders. There was always an implicit understanding that love was very conditional, often based on achieving good grades and behaving properly.

Many of us grew up with chappal — sandal — diplomacy. If you messed up, you would figuratively “eat” the chappal or be threatened with eating the chappal in the near future. Yet here’s this strange man, my father, scolding me on FaceTime for using a firm voice with my son, who was running around naked throwing Lego pieces in the air. “He is special and very smart,” my father informed me without providing evidence. “You have to be gentle with him.”

When I was growing up, my father did plant big, wet kisses on my cheeks, which I would wipe off with my palms. There were our weekend trips to comic book shops, consistent encouragement for my artistic endeavours, many terms of endearment (“Wajoo Baba” — no one calls me Wajahat in my home) and comparing me to pieces of organ meat in Urdu (it’s a sign of affection). However, there were no “I love yous” or PTA meetings attended.

Unlike me, my father didn’t spend two hours with the family on a Thursday night testing a dozen double strollers at Babies “R” Us, after already investing significant time researching different brands and prices. I also have zero memories of my father taking me to hang out with other brown dads wearing their babies in a 360 Baby Carrier at a park on a weekday without any wives present. In fact, if you saw several brown men alone with babies in a playground in the 1980s, you would be excused and applauded for calling the police.

Cultural change

My father does notice the difference. He tells me that for his generation it’s a cultural change. When he was young, he said, fathers weren’t expected to sit near their wives or even hold up their kids in public. My grandfather, whom I remember as being affectionate with me, was not “demonstrative” when my father was growing up. My father doesn’t blame him for his reserve. They were victims of partition, traumatised, forced to migrate to a new country. Even though they were loving, my father said “they had zero capability” to express their love as we do now.

“We don’t have the words for it in the language,” said my father-in-law, a retired Pakistani-American doctor, meaning there’s no phrase that is the literal equivalent of “I love you” in Urdu or Hindi. He now uses it all the time, not just for his grandchildren, but also with my wife and her siblings. He credits American culture and his kids for helping him learn how to express it.

I was thinking about all this recently as I was opening my Ramadan fast with a few friends, all children of immigrants, who are now parents. We were trading stories about how our parents have mellowed with age, softened with our kids and resorted to using Bollywood melodrama when it comes to guilt and discussions of mortality. We realised our parents are old now. Time can’t be taken for granted.

None of us had ever told our parents “I love you.” None of us had ever heard it from them.

I came home and called my father. I asked him why he never said it. He reasoned you don’t have to say it to show it. Indeed, it’s true, and my privileged life and upbringing was a testament to that. “Sometimes people say it so much that it sounds hypocritical,” he said. “It becomes just words, and words don’t mean anything.”

But some words do have meaning. They don’t have to be hoarded. They don’t need formality. They can and should be given out freely. And it’s a sentiment that makes for a pretty economical gift.

—New York Times News Service

Wajahat Ali is a playwright, lawyer and contributing opinion writer.