Given the choice, most footballers would rather take a penalty than stand in goal. This explains why political incumbents are generally reluctant to do televised debates, and challengers are keen. A serving prime minister has to defend a record that will inevitably include blunders and unpopular decisions. The opposition gets to attack, which can still produce humiliating misses — but the target is wide.

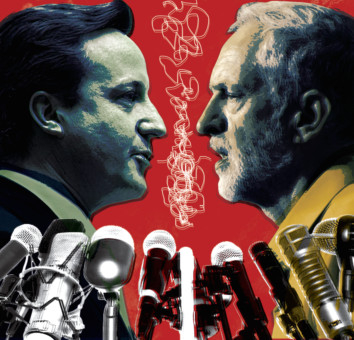

That is why Britain’s Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn has proposed an annual “state of the nation” debate, in which British Prime Minister David Cameron and his rivals would kick around the issues of the day on live TV. The Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) leader, Nicola Sturgeon, and the Lib Dems’ Tim Farron have signalled their willingness to play; Downing Street has said it will “look at the formal details of any proposal”, which is throat-clearing in advance of saying no. When it comes, the refusal will be configured in terms similar to Cameron’s efforts at avoiding TV debates before the general election: The opposition leader gets to interrogate the prime minister every week in parliament, broadcast live.

That is the proper constitutional mechanism, and it should not be downgraded for some parvenu Strictly Come Politicking. As in the run-up to May, Cameron could soon find himself isolated in this argument, but in possession of a strong hand. Broadcasters like televised debates and there is good evidence that they engage voters — but only if there is an A-list cast. Without the prime minister, there is littlepoint, and he cannot easily be shamed into attendance.

The cost-benefit equation for No 10 is simple: It is better to take the certainty of being called a coward over the possibility of blundering before an audience of millions. The prime minister is routinely called much worse in the forgettable daily tumult of Westminster bickering. A month of being called a chicken when no one is listening beats an hour of basting and stuffing when everyone is watching.

The cost-benefit equation for No 10 is simple: Better to risk being called a coward than blundering before millions. In the end, Cameron agreed to a diluted form of multiplayer TV debate, but he held out long enough to deny Ed Miliband the format he craved: A head-to-head between the two candidates with a chance of being prime minister, the choreography of which would, they hoped, have bestowed some much-needed gravitas on the Labour leader.

Corbyn is years from a general election but already his calculations look similar. Already his ratings are the worst of any freshly chosen leader since Michael Foot, although loyal supporters will blame anyone but their champion for the malaise. He has been traduced by saboteur MPs and maligned by the press, they say. It follows that Labour’s front bench should be purged of naysayers and a way be found to project the leader’s virtues without inky contamination by Tory-loving newspapers. Hence, a shadow cabinet reshuffle is mooted for January and the call goes out for a televised hustings.

Although it is questionable that more Corbyn on TV naturally translates into more Corbynism in the country, the Labour leader is right that audiences are ill-served for serious debate that focuses on policies and ideas. The notion that prime minister’s questions fulfils any kind of check on the executive is laughable. Occasionally a cute barb or misjudged riposte reveals something about the character of one of the protagonists. But these are the fine hermeneutics of Westminster politics, not the stuff that swings votes.

Tune in on a Wednesday lunchtime and you will see opposition MPs asking Cameron to confess his wickedness (he refuses) and loyal Conservatives inviting their leader to share their admiration for the government’s good deeds (he does). The whole spectacle unfolds against a white noise of polished bellowing like a farmyard after elocution lessons. The few occasions when leaders have clashed on TV have all been more dignified and revealing.

One objection to TV debates is that the camera promotes thespian agility and slick appearance over substance and content. But that is already a feature of politics; a long, live broadcast at least allows time for masks to slip. The better reservation is that a broadcast “state of the nation” bonanza would represent another downgrade for parliament as the supreme authority in British politics.

The legislative process is cumbersome and arcane, but being inaccessible does not make it irrelevant. There is a populist strain to the argument that equates healthier democracy with better spectacle — a televised joust followed by post-match analysis and an instant poll naming winners and losers. It is of apiece with the appetite for referendums, online petitions and membership surveys — politics by show of hands, which, it is presumed, satisfies the public faster than the obscure machinations of discredited MPs. Within hours of Corbyn’s challenge to Cameron, Nigel Farage had called the Labour leader out to debate Britain’s membership of the European Union. And why not? Nearly four million people voted for United Kingdom Independence Party in May, yet Farage doesn’t even get to ask questions in parliament. If the TV studio is the place where authentic politics is aired, why argue the toss in rancid old Westminster at all? You could email legislation out to MPs and they could write their objections straight into Hansard. The reason is that, for all its flaws, parliament is the home of British democracy. Corbyn has good reasons to want to debate Cameron elsewhere. He doesn’t think the Commons’ style works for him or for the public. He is right. The country needs more substantial debate on policyand ideas. Maybe I am naive in hoping the ideal venue for that might still be the Palace of Westminster.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd