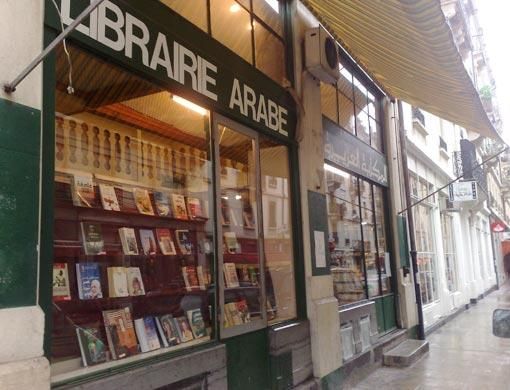

Right in the heart of Geneva lies the Zaytouna Arabic bookshop, a fairly large shop for the relatively small Arab population of the city. But the primary targets of this shop are not Geneva residents. Zaytouna has a special clientele.

"Geneva Arabs do come here but most of my sales are to visiting Arab heads of governments, ministers, royalty and other officials," says its owner, Alain Bittar, an Egypt born French-Sudanese national.

Why would Arab officials shop at a bookstore in Geneva?

"Because here they find books that they won't find at home," he explains.

It is a sad irony, says Bittar, that censorship in the Arab world is the secret to the survival of his bookshop, which has been operating for more than 30 years. "It's my companion," he says. Most books that don't pass the censors in the Arab world can be found at Zaytouna.

Favourite store

Bittar has a number of high profile customers. He recalls: "A member of a Gulf ruling family once called me upon landing in Geneva. 'Alain, what books do you have that are banned in my country', she asked. I said, 'Ask me which books I have that are not banned in your country'. She asked me to put them all in a bag and wait for her driver to collect them".

High profile personalities from the Arab world are attracted to his bookshop because they can buy books that are banned in their countries, and do so anonymously. "Some come in to buy the books and leave quietly, while others like to bring their guards and be officially introduced," he says.

Other visitors to his shop are those nostalgic Arabs exiled in Europe, such as Egyptian businessmen or Iraqi Jews who had to leave their countries decades ago. "Reading Arabic books is a way for them to keep in touch with the Arab world they grew up in and can't return to," says Bittar.

A critic of censorship, Bittar says the banning of taboo topics in the Arab world has led Arab authors to write controversial books that are likely to be censored or banned, thus increasing their appeal in the Arab world (as well as his sales), and negatively affecting the quality of Arabic literature available. "I had one customer who asked me to recommend a book. When I handed him one he asked whether it was banned in his country. I said no and he automatically concluded that the book was a lie," he recalls.

Loss of credibility

The tight censorship policies practised in the Arab world, says Bittar, have led Arabs to dismiss anything that passes their censors as propaganda, and anything that doesn't as the truth governments don't want their people to hear. Banned books, he adds, often have more credibility than those that are available on the shelves of bookshops in the region.

Bittar says he humbly tries to explain to the Arab officials and leaders who visit his bookshop that the tighter the noose is on Arab writing, the more governments' credibility with its people declines.

One of the books banned in the Arab world that is available in Zaytouna is Shams Al Ma'arif Al Kubra (The Sun of Great Knowledge), an old black-magic book. It is banned in much of the region and is considered so exotic that it has websites dedicated to it. Bittar said an Arab woman once walked into his shop just to see the book, but refused to touch it out of fear of its powers.

Such "petty superstition", he says, would have less appeal to Arabs if such books weren't banned in the Arab world.

Other books banned in the Arab world that sell at Zaytouna are cookbooks that have pictures of alcoholic drinks, books about Arab leaders, books on atheism, religious books on Christianity, Judaism and the Shiite sect of Islam, as well as books dealing with sex or horoscopes.

So far, says Bittar, his bookshop is facing no threat of closure "since unfortunately the censorship situation is not getting any better".

A peep into treasure trove of banned books in Geneva

Gulf News exclusive: A peep into treasure trove of banned books in Geneva