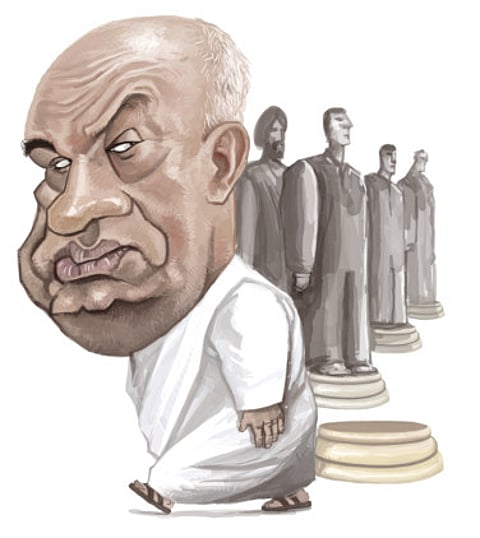

Deva Gowda: A dignified detachment

Becoming prime minister was the crowning moment of Deva Gowda’s political career, but he lacked the qualities of a great leader

Dubai: The “fourth choice for the Third Front”! That was how Haradanahalli Doddegowda Deve Gowda’s candidature for the post of India’s 11th prime minister was described in the corridors of power in New Delhi during 1996, when no single party could stake claim to form a government in the world’s largest democracy.

In every sense, 1996 was the summer of discontent, of political vendetta, of one-upmanship, of “historical mistakes” and, of course, — a summer of the underdog in Indian politics. And all of that catapulted a peasant-politician from rural Karnataka to the most important public office in India.

Gowda had arrived on the national political scene as a consensus choice and compromise formula to stitch together a fledgling coalition at the Centre to offer some semblance of a working title to governance in a post-Congress milieu.

The 1996 general elections saw Congress end up with its worst tally since the first Lok Sabha polls in 1952.

With 140 seats in the 542-member Lok Sabha (Lower House of parliament), Congress was not even in the race to form a government and the then president of India, Shankar Dayal Sharma, invited the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, to form the new government by virtue of having emerged as the single largest entity in the Lok Sabha with 162 seats.

However, the Vajpayee government lasted just 13 days, having failed to muster the required numbers on the floor of the House. So, it was a summer of discontent — over failed promises and missed opportunities — for both for the Congress and the BJP.

Having realised that it was in no position to get anywhere near the prime ministerial post, Congress, led by its de jure leader Sitaram Kesri and under the directives of its de facto power centre, Sonia Gandhi, decided to play king-maker: Ostensibly, to avoid another general election, but driven in reality by its desperation to stay relevant in national politics.

PM aspirants

So it was more of a political vendetta and a game of one-upmanship to keep arch-rival BJP away from power that led the Congress to back a ‘Third Front’ at the Centre, knowing well that it wouldn’t take long for fissures to show up within a concoction of a political entity comprising 13 parties with such disparate elements as the Janata Dal and Left Front in its fold.

Thus began a long and arduous search for a suitable prime ministerial candidate to lead a non-Congress, non-BJP front at the Centre. With former prime minister Vishwanath Pratap Singh flatly refusing to take the mantle, veteran Communist Party of India (Marxist) leader and then West Bengal chief minister Jyoti Basu’s name was floated as a consensus candidate for prime minister. Basu was keen on the job, but it was his party, the CPI (M), that threw a spanner in his works, arguing that taking up the prime minister’s post would limit the party’s ability to criticise a coalition government.

With Basu out of the frame, attempts were made by a section of the United Front constituents to prop up G.K. Moopanar, leader of a breakaway faction of the Congress party, as a likely prime ministerial candidate. However, many of the Congress leaders had an axe to grind with Moopanar and in any case, he was not a universally acceptable name within the United Front itself.

Regional satraps

This impasse paved the way for then chief minister of Karnataka, Gowda, 62, to emerge as what was rather derisively referred to as the “fourth choice” for prime minister from the 13-party hotchpotch.

Gowda’s rise to power marked a huge aspirational leap for the marginalised section of political strata that has inhabited the fringes of the great power game at New Delhi and the Hindi heartland. In that sense, Gowda becoming the premier of India was an acknowledgement of the growing clout of regional satraps in national politics.

Gowda happened to be the first non-Hindi speaking prime minister of the country.

Writing about the leadership vacuum that characterised national politics in the days leading to Gowda’s coronation, John F. Burns observed in the New York Times on April 12, 1997: “For many, the political disarray has come as a symbol of the wider malaise afflicting India as it approaches its 50th anniversary of independence.

“Mr Gowda, a regional politician from the southern state of Karnataka, who styled himself as a ‘humble farmer’, comes to bring a populist touch to India’s elitist political traditions, said he intended to use his tenure to attack deep-rooted problems of poverty, illiteracy and disease.

“But he spent much of his time manoeuvring to keep his tottering coalition together, drawing disparaging comparisons from political commentators to the more charismatic leaders of the past, including Jawaharlal Nehru and his daughter Indira Gandhi.”

Born in the village of Haradanahalli on May 18, 1933, Gowda is an influential member of the Vokkaliga community. He is the current national president of Janata Dal (Secular).

Agrarian roots

Coming from an agricultural background, Gowda was well aware of adversities an average Indian farmer has to face in his daily life. It is no wonder that in his later life, he tried to champion the cause of the rural community and that of farmers.

This is one aspect of his life that has always helped him stay firmly connected to his roots like a true ‘son of the soil’. Despite earning a diploma in civil engineering, Gowda opted to join politics. In 1953, he joined the Indian National Congress and stayed with the party until 1962.

In 1962, he was elected to the Karnataka Legislative Assembly as an independent candidate from the Holenarasipura constituency and went on win that seat for six consecutive terms until 1989.

Later, during the split in the Indian National Congress, he joined Congress (O), one of the breakaway factions, and went on to be the leader of the opposition in the state Assembly from March 1972 to March 1976 and again from November 1976 to December 1977. Gowda endured imprisonment during the Emergency from 1975-77.

Rise to power

It was after joining the Janata Party that Gowda’s career graph really took off. He served as a minister under the chief ministership of Ramakrishna Hegde from 1983 to 1988.

He was elected to the Lok Sabha in 1991, but state politics was always at his heart. Even when in Delhi and heading several important parliamentary committees, Gowda never lost touch with people at the grassroots level in Karnataka. This found an immediate resonance with his state party members and workers when he was elected president of the state unit of Janata Dal in 1994.

Later that year, it was under his leadership as the party president that Janata Dal went on to win the Karnataka Assembly polls. Predictably, the mannina maga (son of the soil in the Kannada language) became the chief minister.

Becoming the prime minister in 1996 was indeed the pinnacle of Gowda’s political career, but it also exposed him to the subterranean tensions, clash of interests and vagaries of political rivalries. One did not have to be an expert to predict that Gowda’s stint at the helm would not last for long.

The Congress was never comfortable with life without power at the Centre. So the string-pullings and covert threat to topple the Gowda-led government were always there. Moreover, many of the constituents of Gowda’s own government were ill at ease with the intrinsic dynamics of coalition politics.

The Kesri-led Congress raised the bogey of no-confidence against Gowda’s government, claiming that it had not been consulted before many key policy decisions.

Maintaining a rather hardened stance towards Congress machinations and refusing to grovel at the beck and call of the Congress high command, Gowda made things difficult for himself too, resulting in a withdrawal of support by Congress and a consequent vote of confidence in parliament that Gowda lost.

A defiant Gowda insisted: “I am satisfied that in these months, I have not betrayed my people. I have not betrayed my nation.” His reign at the Centre came to an abrupt end on April 11, 1997, leaving historians little to worry about a 10-month legacy.

Gowda did have his hour in the sun, but will hardly ever be counted among the pantheon of greats in the hall of fame of Indian politics. He continues to be a member of the Lok Sabha, but his voice is hardly ever heard inside or outside parliament.

Far from being firebrand or charismatic, the Gowda brand of politics is characterised by a dignified detachment to hype and gimmick. He is one politician who is reconciled to fate, even though his days in active politics haven’t ended yet, and one who has absolutely no complaints about that Eliotesque lament:

‘This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends