For over a year, since the uprising against President Bashar Al Assad’s regime in Syria, information about the revolution has been transmitted to the rest of the world by a group of street journalists. These men are not trained reporters, but risk their lives every day to provide information to the international press.

In the absence of sophisticated equipment, they use camera phones, point-and-shoot cameras and the like to fill the holes left by the mainstream media. The inability of most professional reporters to gain access to the area to document the conflict has turned these men into a major source of information on Syria, a country in the grip of a civil war that becomes bloodier and bloodier every day.

What follows is my detailed diary of meetings and events that recently took place in Syria in the company of these brave men.

June 19, 2012: I arrive in Al Qusayr, a town 20km from the Lebanese border, an important entry point for weapons and medicine, and also an escape route for civilians. For more than four months, this town of 50,000 people has been shelled by government forces who are trying to regain control by tearing at the throats of the rebel army. The bombardment occurs on a regular basis every day, especially during the demonstrations that occur after prayers. I am greeted in Al Qusayr by the young activists who run the media centre there.

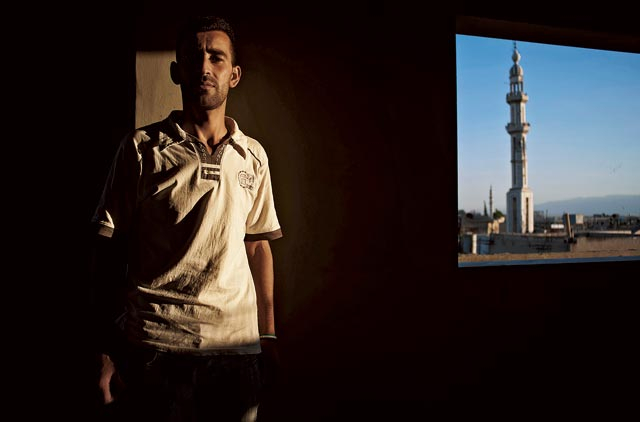

Hussain, the director of the news dissemination centre, is 26 years old, has tired eyes and the weariness of someone who is much older. Before the war, he worked in his family’s construction business. He greets me warmly and tells me he is the only member of his family who has stayed in Al Qusayr. He couldn’t leave as he had to run the media centre, organising the work and coordinating his activist friends.

Like the other young men in the media centre, Hussain has worked tirelessly for more than a year. He wakes up at dawn every morning to gather more updates about the war. He just has enough time to grab a bite, then he heads off on a motorcycle to begin his daily interviews with the soldiers of the Free Syrian Army, or to document the previous night’s shelling. In the evening he has time for a meal with friends, and then he is back on the computer working, responding to foreign journalists who ask about the situation in Syria. At the end of the day he usually falls asleep exhausted, often at work.

June 20, 2012: It’s 4.50am and the city is under heavy bombardment. It lasts for more than two hours and at first, I am the only one who’s awake. Hussain and the other media centre guys are fast asleep, unaware of what’s going on. One rocket falls near our building, sending up a column of black smoke. I am shocked by the proximity of the explosion and, while I try to gather my wits, I realise that 28-year-old Fadi has woken and is already at work, video camera in hand. Five minutes later, the former wedding videographer has uploaded the footage. We go back to sleep. The scene puts a wry smile on my face. Abu Shamsoo, a former elementary school teacher, tells me, “Do not be surprised, friend. This is normal, we have been under bombardment for more than four months, and we have to live with it.”

June 25, 2012: I accompany Hussain and Fadi as they head off to interview an army deserter. The two young men work very much like a team of professional war correspondents, the only difference being they have amateur equipment, no cash and no security. Their report will be distributed by the Orient Network, which uses the activists’ videos. Since there are no foreign correspondents around, this is the safest and most economical way for them to get images from Syria. The network can also now avoid the risks and save on the mandatory insurance cover for Western journalists. Each interview, photo, scrap of information, bombing or injury is edited by the group and screened. Everything is published on the web and on YouTube.

Trad, a 37-year-old hyperactive reporter, records everything that happens in town and he never stops – except to drink mate (a herbal tea of South American origin). Before the uprising, he ran his family’s shop selling furniture, and in summer he worked in Cyprus. A few days later, I follow him to the local hospital where doctors tried in vain to save his cousin’s life. After a year under siege and seeing the fourth member of his family killed by the army, I thought he was going to crack. But a few hours later, Trad was back to his usual self.

June 27, 2012: At lunchtime I go with Muhannad to buy food for the media centre. Muhannad multi-tasks between his jobs as the guy who runs the kitchen, a part-time cameraman and contact person for the Free Syrian Army. The 27-year-old doesn’t speak a word of English and, unlike most of the men in the media centre, he has continued working in his family’s tailor shop. The shop produces combat jackets complete with magazine pouches for rebel fighters in less than an hour. Muhannad’s an amazing cook who, with few ingredients, can make culinary magic using a single, often malfunctioning, electric stove.

June 30, 2012: Jaffa accompanies me for two nights around the city, dark and deserted after shells demolished the power station. The calm and affable Jaffa was a primary school teacher before all of this began. He now goes around documenting the bombing of his city. He readily agrees to be my guide for a photographic tour by moonlight. There is no one better than him to guide me through the dark deserted streets without fear of being shot by a government army sniper. He stops by a shop that makes tombstones. “It’s been a year when they’ve been working like crazy! At the end of the war they’ll be the richest people in the country,” he says.

It seems incredible to me that these young men have built up such a rapport with death. For the men of the media centre, this is a personal war. They feel it more than the few foreign reporters who are here.

July 2, 2012: Al Jazeera has asked the guys to do an in-depth report on the victims of Trad’s family – an inside story. Trad and his brothers are asked to recall the moments when their relatives died in the shelling. The eldest of Trad’s brothers, a 50-year-old doctor, bursts into tears as he flips through caricatures drawn by his dead brother.

July 5, 2012: I accompany Hussain to the home of some other activists who are preparing posters and banners for a demonstration after Friday prayers. I’m happy because I think I’m going to get to photograph a real demonstration, but they explain to me that there won’t be one because the few people left in the city are afraid to go into the streets. Whenever the army becomes aware of groups of people gathering in the main square, they increase the shelling. The men still prepare peaceful slogans against the regime.

July 7, 2012: The press centre has no internet connection because the generator is broken and the power supplied by car batteries isn’t enough. Hussain tries to charge a battery using a solar panel on the roof, but unfortunately it can’t generate enough electricity to operate all the equipment, so we are disconnected. No internet means no communication with the outside world. We must wait for the generator to be repaired. We console ourselves with a cup of tea.

July 11, 2012: Yet another day of heavy bombardment. The wounded arrive at a nearby hospital. Hussain tells me to move quickly because a government helicopter is flying over the city and will shoot on sight. Together with my partner, I enter the room that is being used as a hospital, and the sight that greets us is appalling: all the casualties are children, five of them in total, two of them dead on arrival. The mortar shell was a direct hit.

The doctors work frantically, trying to save children who are in serious condition. Hussain records the scene then he puts the video camera down and begins helping the nurses who do not have enough hands to hold the drips needed for the wounded. A shell lands close by, and everything shakes, but the hospital staff don’t stop. The children must be saved. Boom! Another shell explodes outside the hospital entrance. Hussain takes the video camera and goes to record the scene, but as he is leaving another mortar shell falls nearby, blocking the door.

The shelling ceases in about 30 minutes and we return to the media centre. A crowd has gathered there, eager to see footage of the shelling. Not out of curiosity, but to check if any of their family have been killed in the shelling. The rebels use the media centre’s internet connection to communicate with their families who have fled to Lebanon.

I tell Hussain that I need to leave Syria as soon as possible. I have to sell my work and can’t do it from here. My young friend looks at me sadly. I can sense a feeling of abandonment in his eyes and I feel cowardly for not staying, but I must go. I’ve had enough. After more than 20 days of bombardment and death I need to get away. I don’t have his strength, nor his courage.