Washington: President Barack Obama’s outreach to Iran to help thwart Sunni militants in Iraq may upset regional allies and risk a domestic political backlash.

The United States began the discussion with a brief meeting on Monday between American and Iranian officials on the sidelines of talks in Vienna over Iran’s nuclear programme, according to a State Department official who wasn’t permitted to be quoted by name.

The contacts may open the door for what would be the first regional security cooperation since Iran helped the US take on the Taliban in Afghanistan after the September 11, 2001, attacks. The Obama administration wants to see whether Iran, which has close ties to Iraq’s Shiite-dominated government, will support political changes to weaken the Sunni militants threatening to split apart the country.

The US is trying to persuade Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Al Maliki to make his government more inclusive with minority Sunnis and Kurds, who have been shortchanged under his rule.

Unless Iran shows it will play a constructive role in pushing for political change, “I see talks with Iran as being counterproductive, alienating the regional states who would see this as very threatening to them,” former Defence Secretary William Cohen said in an interview on Monday on Bloomberg Television.

Reaching out to Iran has consequences for US relations with Israel as well as Saudi Arabia, said Robert Satloff, executive director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy in Washington. Partnering with Iran on Iraq would be a “huge and profoundly misguided game-changer about the regional balance of power,” he said in a phone interview.

“A partnership with Iran would confirm in the eyes of our traditional Sunni partners and confirm in the eyes of the Israelis, whether it is true or not, that the United States had realigned its alliance structure,” he said.

Over the weekend, Kerry called his counterparts in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Kuwait to discuss Iraq.

Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah “hates Al Maliki and wants the Al Maliki government to go away,” said Colin Kahl, a former deputy assistant secretary of defence for the Middle East.

Still, the Saudis don’t want to see Sunni militants “establishing a caliphate” in Iraq and “they’ve no interest in Iraq becoming a failed state,” said Kahl, who is an associate professor at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University in Washington.

In Iraq, there is a strong hope that the US will mediate the crisis, said Manal Omar, associate vice-president for Middle East and Africa at the United States Institute of Peace, a non-partisan Washington policy group funded by Congress.

Speaking by telephone from Abu Dhabi, Omar said “the very same people, the very same political groups who were lobbying for the US to pull out, for the US not to have an active role in Iraq, are the ones who are looking and asking for the US to intervene now.”

In the US, any accommodation with Iran is complicated by Iran’s record, which includes support for terrorist groups such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah and helping to kill American soldiers deployed in Iraq.

Before any talks, “the US should demand that Iran apologise to families of US service members it killed in Iraq and Afghanistan,” Mark Dubowitz, executive director of the Foundation for Defence of Democracies in Washington, said in a message on Twitter.

Obama said last week that he was looking for evidence that Al Maliki will address the underpinning of this crisis before deciding on air strikes and other support. Monday, he met at the White House with his national security team, including Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel, Secretary of State John Kerry and Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Martin Dempsey.

“We’re not talking about coordinating any military action” with Iran, State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said on Monday. The US continues to have “significant concerns about Iran,” she said, citing its support for terrorist activity, the detention of American citizens inside Iran, and the unresolved negotiations over its nuclear activities.

The offensive by the militant Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, with help from disaffected Sunnis, threatens to plunge one of the world’s largest oil producers into a sectarian civil war like the one in neighbouring Syria. In that conflict, the US is backing rebels it deems moderate while Iran sends arms and fighters for President Bashar Al Assad, whose Alawite faith is an offshoot of Shiite Islam.

By contrast, “the strategic goals of the United States to preserve some semblance of government in Iraq and to resist the encroachments of this extremist force coincide with Iran’s interests,” said David Cortright, director of policy studies at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame in Notre Dame, Indiana.

“It would be foolish not to take advantage of those convergences of interest to try to solve this problem,” he said.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that Iran is interested in cooperating on US terms. The commander of Iran’s elite Quds Force, General Gasem Sulaimani, has been consulting in Iraq on how to roll back the Sunni forces, according to Iraqi security officials cited by the Associated Press.

Sulaimani’s involvement raises questions about whether Iran is looking to stand behind Al Maliki in a sectarian civil war, as Iran is doing in Syria.

Within Iran, the memory of the 1980-1988 war with Iraq — in which a combined one million people died — creates deep divisions about what to do about Iraq today, said Haleh Esfandiari, director of the Middle East Programme at the Wilson Centre, a Washington policy group.

“No matter how close the Iranian leaders and Al Maliki are, or pretend to be, among the ordinary Iranian population, there is no love lost for Iraq,” Esfandiari said.

Any US moves now in Iraq have the complexity of a Rubik’s Cube, with political consequences both at home and in the region.

“There’s a whole lot of forces at play here,” Kerry said in an interview on Monday with Yahoo News.

The US outreach to Iran comes at a sensitive moment, as the US and its allies seek a nuclear agreement before a deadline next month.

Amid their history of enmity, “Iran and the US need each other, and both of them need to recognise the other’s ability to play a stabilising role,” said Trita Parsi, president of the National Iranian American Council.

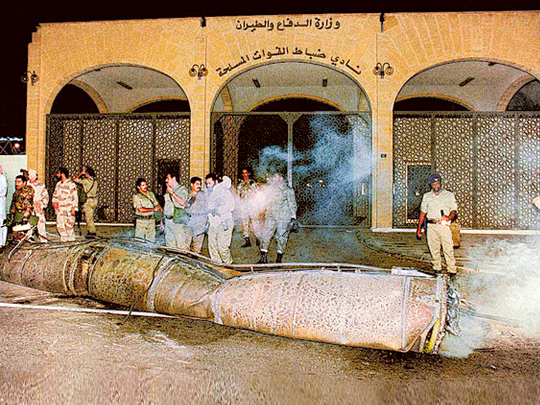

While there was some cooperation with Iran as President George W. Bush launched a war against the Taliban following the 9/11 attacks, Iran has supported militants in Afghanistan and Iraq with training and weapons, including designs for enhanced roadside bombs that killed and maimed many American troops.