Damascus: The ground-breaking agreement on establishing de-escalation zones in Syria, signed by Russia, Iran and Turkey at the fourth round of the Astana talks last week, provides for demilitarising the eastern countryside of Damascus, the northern suburb of Homs, the northwestern city of Idlib, and the southern one of Daraa.

Syrian warplanes will be prevented from flying over these four districts, let alone attacking them, and they will off-limits to tanks, soldiers, and heavy arms.

The pro-regime elements are unhappy with the agreement but they have been forced to accept it, given that it is the brainchild of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The deal calls on Syrian regime to halt all attacks and to guarantee that schools, police, and basic services like electricity and water return to these four districts — but only after the ceasefire holds.

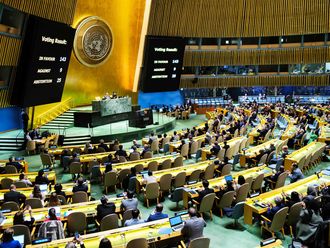

The “Putin Agreement”, as it is being called on the streets of Syria, hopes to get cemented into a UN Security Council Resolution by early summer this year.

From there, it is likely to include other parts of the country, like the countryside of Aleppo in the Syrian north, and the suburbs of Latakia on the Syrian coast.

Turkey, Iran, and Russia will serve as “guarantors” of the agreement, with each side making sure that its proxy on the battlefield accepts and upholds what was decided upon in Astana by the “Big Three”.

The Riyadh-backed High Negotiations Committee is furious with the agreement, not only it was cosigned by Iran but also because it legitimises the Syrian regime within the international community, as a partner in reconciliation.

In an official statement they wrote off the deal saying that it lacked “the basic minimum of sovereignty” because it justifies the permanent presence of an international peacekeeping force in Syria, composed of “non-controversial” countries like Egypt, Algeria, and member states of BRICS (India, China, South Africa, Brazil, and of course Russia).

There is no decision yet on how to raise funds for this international force, what its exact duties would be, and when or how its mission would end.

There is also no agreement to date on how they would react to any violation of the ceasefire.

The Astana agreement also fails to mention the fate of Syrian prisoners, and it has no specific clause for the right of return of Syrian refugees.

It also does not say whether the residents of these four “de-escalation” zones will be allowed to commute throughout Syria, or remain confined to their geographical borders — and being treated as outlaws in the rest of the country.

Abu Mohammad Shams Al Deen, a resident of Eastern Ghouta, the agricultural belt surrounding Damascus — which has been held by Saudi-backed rebels since 2012, told Gulf News: “We have been given no assurances yet that if we accept the agreement, they won’t come after us. We need to be assured first — and we take orders from nobody, neither from Damascus or members of the opposition who are living in their five star hotels.”

In theory, the deal means that unlike other reconciliation agreements, which collapsed before they got past the drawing board, this time, residents will not be deported to other parts of the country but will be allowed to stay home and take part in the rebuilding of their destroyed towns and villages.

They will also not be harassed or arrested for taking up arms since 2011.

Ultimately Putin wants to prove to the world that he can deliver when it comes to Syria and he used his paramount influence to secure the blessing of Damascus, which had previously refused abiding by such formulas — especially when it came to the grounding of warplanes or accepting international monitors.

Firas Tlass, a Syrian businessman based in Dubai predicted that the agreement would collapse “within weeks” because Iran is unhappy with it and unwillingly cosigned it in Kazakhstan.

It was actually planned by the Russians, he noted, “to curb the wild behaviour of Iran” on the Syrian battlefield.

Shams Al Deen added, “The only way that this agreement will succeed if the Iranians are pushed out of the scene. We would need a new election law and a new local administration law that would give these four districts the right to elect their own municipality and parliament, appoint their own governors, and get a share of their own natural resources. These places cannot return to Baathist rule.”

All of this, it must be noted, is specifically mentioned in the Russian-wrote new Syrian constitution, put forth by the Kremlin since mid-2016.

The Syrian government had shunned the constitutional draft, objecting to the reduction of presidential powers that it contained and to the specific mention of local parliaments, giving Syrian districts a federal form of government that breaks the paramount dominance of Damascus.

At the forthcoming round of UN-mandated peace talks in Switzerland on May 15, known as Geneva VI, Syrian negotiators will be tasked with debating the Russian proposals for the Syrian constitution. According to sources in Damascus, “it is the only serious topic on the agenda” and Putin wants it to see the light by December 2017.