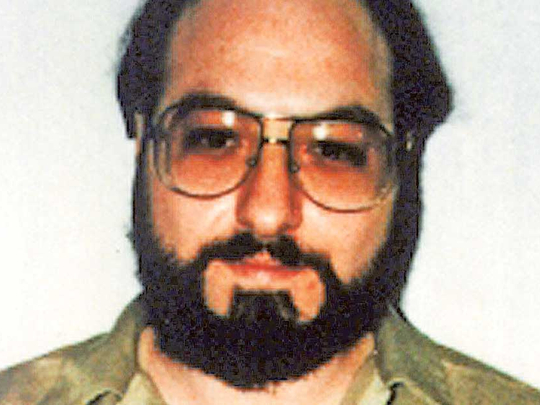

Washington: The freeing of Jonathan Pollard, who was arrested in November 1985 after passing secret documents to Israel while working as a civilian analyst for the US Navy, could be an important moment in relations between the United States and Israel, which has long campaigned for Pollard’s release. Pollard will become eligible for mandatory parole this fall after 30 years in prison, and the US Justice Department signalled Friday that it will not oppose the release.

Why is Israel so keen to have Pollard freed? And why has the United States resisted releasing him for so many years?

Why Israel wants him free

To his supporters in Israel and elsewhere, a number of key factors in the case support releasing Pollard. For one thing, although Pollard admitted that he had handed over a huge amount of documents to Israel, he has argued that he did it out of an idealistic loyalty to Israel (a key US ally), not malice, and that the information was about Arab states, Pakistan and the Soviet Union, not the United States.

A web site dedicated to documenting Pollard’s case for supporters argues that Pollard was simply breaking past an informal embargo that some US officials had put on sharing intelligence with Israel. Another argument was made in a recent legal analysis published in the Jerusalem Post that found Pollard’s sentencing was too harsh. The analysis pointed out that Pollard had cooperated with the investigation and accepted a plea deal in which the prosecution did not ask for a life sentence. (The judge in the case imposed it, anyway.) Mordechai Kremnitzer, a vice-president of research at the Israel Democracy Institute, also pointed out that other Americans convicted of spying had received more lenient sentences.

Why the US said no

Many in the US intelligence community feel strongly that Pollard should not be released prematurely: In 1998, George J. Tenet, then director of the CIA, apparently scuppered a deal with Israel on Pollard by threatening to resign if the spy went free.

There have been a number of arguments that Pollard’s spying was far more damaging than others care to admit.

In an op-ed for The Washington Post in 1998, former directors of naval intelligence William Studeman, Sumner Shapiro, John Butts and Thomas Brooks argued that as Pollard’s case never went to trial (because of his plea deal), it never became public that Pollard “offered classified information to three other countries before working for the Israelis and that he offered his services to a fourth country while he was spying for Israel.” The op-ed also argued that the “sheer volume” of documents passed on by Pollard was almost unrivalled, and his support was only the result of a “clever public relations campaign.”

Even now, while his supporters portray Pollard as an ideologue, other critics in the United States point to reports of his drug abuse and history of grandiose lies.

What could come next

Over the past few years, the Israeli campaign to release Pollard has gained momentum, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu expressing official support, and with a number of petitions and protests outside the US Embassy in Tel Aviv. President Barack Obama repeatedly refused to contemplate releasing Pollard and refused to grant him leave for family emergencies.

“As the president,” Obama told Israeli television before visiting the country in 2013, “my first obligation is to observe the law here in the United States and to make sure that it’s applied consistently.”

However, there had been signs of a shift on Pollard, who is now 59 and said to be in poor health. Some unlikely figures, such as Republican Senator John McCain have publicly called for his release.

In 2014, there were signs that the United States was considering pardoning Pollard to aid the Middle East peace process. The hope appeared to be that if the United States agreed to release Pollard, Israel might agree to release some Palestinian prisoners or impose a moratorium on new construction in occupied territory, key sticking points for the Palestinian negotiators. However, Pollard was not released, and there was little progress made in peace talks.

What is happening now appears to be something different. According to the Justice Department, Pollard will become “eligible for mandatory parole” in November, meaning that he will not need to be pardoned to be released. However, the timing of the news — just after the United States and other countries reached a controversial nuclear deal with Iran — has led some to speculate that a release would be aimed at appeasing Israel.