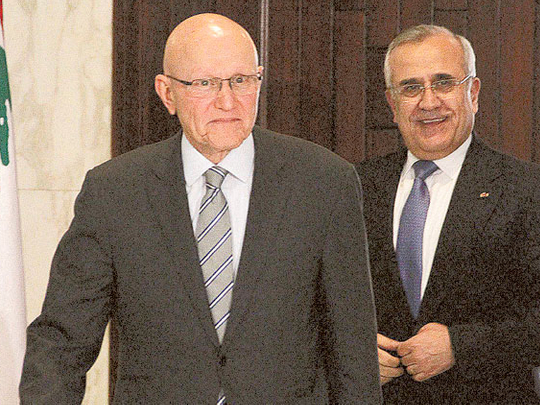

Beirut: Even without the support of Hezbollah and the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), Tammam Salam enjoyed a parliamentary majority that propelled him to the prime ministership of Lebanon, simply because he received the backing of March 14 deputies backed by Druze leader Walid Junblatt for a total of over 69 votes (out of 128).

Against the irresistible tide that highlighted a clear restructuring of the domestic scene after Prime Minister Najib Miqati’s government resigned, Hezbollah and the FPM jumped on the Salam bandwagon, aware that withholding confidence further enlarged the gap that separated them from the majority of the Lebanese. As Gulf News went to press, 124 backed Salam, an unprecedented event in Lebanese political annals.

Notwithstanding the new reality, however, it was fair to ask whether March 8 factions were ready to facilitate Salam’s task to form a caretaker cabinet to oversee parliamentary elections or insist on a national unity government with a longer shelf life.

There were many reasons why Miqati resigned, including FPM manoeuvrings around the so-called “Orthodox Proposal Law,” as well as the pay raise issue for the public sector that the government reluctantly sponsored. Still, nothing was more frustrating than the Bashar Al Assad regime crisis in Syria, as both General Michel Aoun and Hezbollah’s Hassan Nasrallah, pillars of the Miqati Cabinet and who were now more isolated then ever, openly sided with Damascus. Inasmuch as their endorsements led to an acute spillover of the Syrian civil war into parts of Lebanon, the out-going premier was further weakened when he could not handle the impact that the presence of a million Syrian refugees, along with the nefarious consequences of organized smuggling, had on the country.

Tammam Salam was aware of this imminent test that now required an astute winnowing.

Still, Lebanese elites were preoccupied with the upcoming elections, whose legal mechanisms were deadlocked. The new prime minister was aware of this challenge too and told the daily Al Safir: “Reaching an agreement over a new parliamentary electoral law and staging the elections will be my first objectives as prime minister,” hoping that the next cabinet would “work on asserting civil peace and national reconciliation that will pave the way for holding the polls” on time.

It was important to note that the designee narrowed the scope of his government to overseeing parliamentary elections even if no consensus emerged on the law under which such elections might be held. With the so-called “Orthodox Proposal Law” now shelved and lacking an accord over a hybrid alternative, only the current 1960 (as amended in 2009) Law was valid, even if all parties universally rejected it. In the absence of an alternative, only the president of the republic and his minister of the interior, as legally required to do so, called for elections to be held on that basis. In addition to this dilemma, there was also a divergence of opinion over the ministerial statement that now accompanies every government’s inauguration, ostensibly to act as a blueprint to guide officers. A source of deep popular confusion, past statements emphasised Hezbollah’s tryptic “people, army, resistance,” while most March 14 tenors advocated an amended version: “people, army and State.” The erudite Salam insisted that he supported “the resistance against Israel as long as it directs its weapons towards the enemy.” He refused to see “these arms turned towards the internal scene,” and highlighted the importance of the Ba’abda Declaration, which was approved during the last national dialogue session on June 11, 2012 that called for keeping Lebanon away from the Syrian civil war.

The burden on the talented Salam will now be to navigate through these shark-infested waters, with two important tasks ahead: agree on a new electoral law (or go with the 2009 regulations) and hold parliamentary elections more or less on time. Of course, this iseasier said than done, though eminently possible if Hezbollah leaders consent.

For in a rare moment of national glee, observers were genuinely impressed as they watched politicians trek to the presidential palace, to formally nominate Salam for the premiership. It is now up to the affable and gifted Salam to grapple with the inevitable political brawling that all politicians engage in to advance narrow interests. Under Salam’s leadership, officials will be tested on their sense of patriotism and perhaps they will learn how to serve Lebanese citizens.