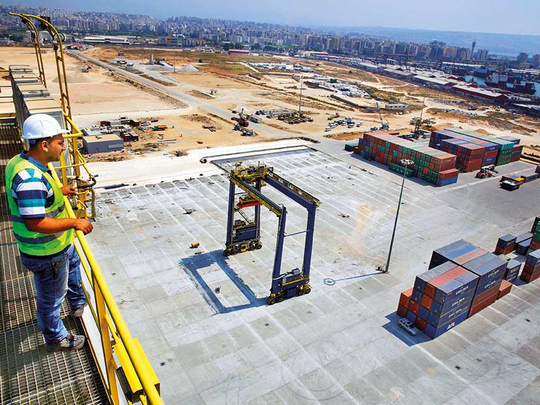

Tripoli: The port of Tripoli in northern Lebanon wants the world to know it’s ready for business.

British safety managers are training local hires to operate heavy machinery and Chinese technicians are running diagnostics on two new container cranes that tower over the harbour, just 28 kilometres from the Syrian border.

After six years of civil war in Syria, markets across the Middle East are anticipating a mammoth reconstruction boom that could stimulate billions of dollars in economic activity. Lebanon, as Syria’s neighbour, is in prime position to capture a share of that windfall and revive its own sluggish economy.

Battles still rage in Syria’s north and east, and in pockets around the capital, Damascus, but the survival of President Bashar Al Assad’s government now appears beyond doubt.

That is introducing an element of stability into forecasts not seen since 2011, when the war broke out. The Damascus International Fair, a high-profile annual business event before the war, is to open on Thursday for the first time since war broke out, with participants from 43 countries.

The World Bank estimates the cost to rebuild Syria at $200 billion.

For Lebanon, that could be just the stimulus it needs — the tiny Mediterranean country’s growth rate has hovered around 1.5 per cent since 2013. And though the capital, Beirut, has grown visibly richer over the years, Tripoli and the impoverished north have lagged behind.

“Lebanon is in front of an opportunity that it needs to take very seriously,” said Raya Al Hassan, a former finance minister from northern Lebanon who now directs the Tripoli Special Economic Zone project that’s planned to be built adjacent to the port.

Ahmad Tamer, the port manager, estimates Syria’s reconstruction will create a demand for 30 million tonnes of cargo capacity annually.

Syria’s chief ports, Tartous and Latakia, also on the Mediterranean Sea, have a combined capacity of 10 to 15 million tonnes, he says. He wants Tripoli port to be ready to step in for a portion of the rest.

“We could provide up to 5 or 6 or 7 million tonnes,” he says.

The port is nearing the completion of the first phase of an expansion project first drawn up in 2009, then revised with an eye on Syria in 2016. Capital investment has reached around $400 million (Dh1,468 million), according to the port manager.

On a map, Tamer pointed to a vacant quadrant where 7/8 preparations are underway to build silos to hold grain destined for regional markets.

Syria’s conflict has decimated its food production, which included an average of 4.1 million tonnes of wheat annually before the war, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation.

In 2017, it managed to produce just 1.8 million tonnes.

Lebanon’s businessmen and politicians have always maintained close relations with Syrian counterparts. Syria is among Lebanon’s largest trade partners, and arguably its most reliable supplier of cheap labour. Lebanon, in exchange, is the banker to many of Syria’s enterprises and its wealthy elites.

These ties give Lebanon — and Tripoli in particular — an edge over competitors vying for the Syrian market.

The city’s location is also attracting foreign investment. Tripoli port signed a 25-year lease with the Emirati port operator Gulftainer in 2013, to manage and invest in the terminal.

“Our aim was to invest here in anticipation of Syria’s reconstruction,” said Ibrahim Hermes, the CEO of Lebanon’s subsidiary of Gulftainer.

Lebanon is now a fixture on itineraries of prospective investors. Hermes said he has seen delegations arriving from Europe, Asia and especially China, to scope out trade opportunities.

Before the war in Syria, goods coming through Lebanon’s ports used to transit as far afield as Iraq — saving ships from having to take the sea journey through the Suez Canal and around the Arabian Peninsula.

There is talk now that Tripoli could even be a terminal in China’s trillion-dollar new “Silk Road” project, carving a trade route from east Asia to Europe.

The Chinese firm Qingdao Haixi Heavy-Duty Machinery Co. sold the two 28-storey container cranes now at the port. Safety signs inside the structures are posted in English and Mandarin.

“Tripoli can be a main transshipment hub for the eastern Mediterranean,” said Ira Hare, a sunburned British manager working for Gulftainer.