President Donald Trump’s recent decision to refrain from certifying the 2015 Iran nuclear deal harks back 38 years to another pivotal presidential decision about Iran. On October 21, 1979, President Jimmy Carter authorised the deposed Shah of Iran to enter the United States for medical treatment — with catastrophic consequences. Carter blundered because of vacillation, shortsighted thinking, a disregard for identified risk and inept implementation that included zero precautions to protect against disaster.

As Trump charts a new course with one of the most powerful nations in the Middle East, Carter’s missteps offer him valuable lessons: When dealing with Iran, a president must verify that information is accurate, consider risks carefully and imagine how one’s own actions will be perceived by Iranians, who evaluate circumstances through an entirely different historical prism.

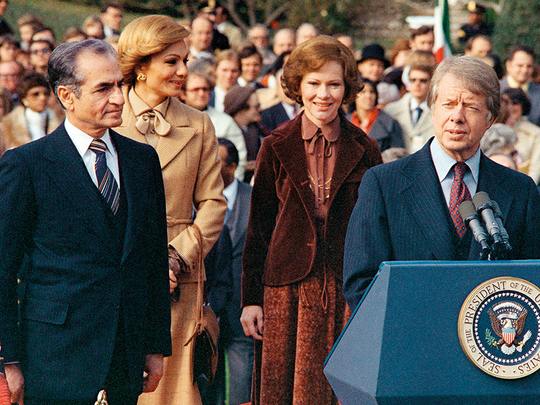

Like his predecessors, Carter considered Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi an ally and friend. In December 1977, he visited Tehran and toasted the shah for making Iran “an island of stability” and for “the admiration and love which your people give you.” It was a delusional toast, one that demonstrated a total lack of understanding of historical legacies and the political fires raging in Iran.

Power was slipping from the shah’s grasp thanks to a growing revolutionary movement inspired by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and nurtured by resistance to royal repression. This revolution reached a tipping point on January 16, 1979, when security risks forced the shah to flee the country.

Carter’s support for the shah did not flag immediately after his regime collapsed. When the shah fled, Carter offered him access to a private estate in California. The shah declined, opting instead for Egypt and Morocco as havens from which he could best nurture his hope — utterly unrealistic — of a restoration to his throne.

Sixteen days after the shah departed, Khomeini returned from more than a decade in exile. He received a thunderous hero’s welcome from millions of Iranians. Over the following months, he gradually consolidated power in a volatile political environment, establishing the Islamic Republic of Iran with himself as its supreme leader.

Khomeini’s return to Iran finally awoke Carter to the political risks of his association with the shah. Within weeks, extremist militants inspired by Khomeini overran the US Embassy and held diplomats captive for several hours before secular government ministers negotiated their release.

US diplomats in Tehran strove to stabilise American-Iranian relations by negotiating various financial, legal and political issues with the government of interim Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan. Those diplomats reported that anti-shah passions were so white-hot that continuing any affiliation with the deposed monarch before revolutionary fervour ebbed and American-Iranian relations normalised would compromise American interests and imperil US officials in the country. Admitting the shah to the United States, Ambassador William H. Sullivan presciently warned, “would almost certainly result in an immediate and violent reaction” that Khomeini would prove unwilling or unable to contain.

Finally recognising the intensity of the anti-shah passion among the Iranian people, Carter withdrew his offer of asylum.

Carter’s recognition of this political reality was immediately tested, however, by domestic politics. Influential conservatives, some within his administration, pressured him to stand by the shah. National security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, along with prominent Republicans Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller, lobbied the president to welcome the shah to the United States, if not conspire to return him to power. Kissinger shamed Carter for treating a longtime ally “like a Flying Dutchman looking for a port of call” and threatened to withhold support for the SALT II treaty, one of Carter’s signature diplomatic objectives.

These conservatives used their leverage to open sanctuaries for the shah in the Bahamas and Mexico after political conditions forced his departure from Morocco. When Carter expressed concern about the possibility of mob violence against US interests in Iran, Brzezinski countered that “at stake were our traditional commitment to asylum and our loyalty to a friend. To compromise those principles would be to pay an extraordinarily high price not only in terms of self-esteem but also in our standing among our allies.”

Carter wavered under this pressure in October 1979. After learning that the shah had cancer, conservatives appealed to Carter’s humanitarian and religious values, telling him that the shah’s condition was grave and that he could not survive unless he received state-of-the-art treatment available only in New York. Recalling how Bazargan had ended the militants’ takeover of the embassy in February, they assured Carter — falsely, it turned out — that Bazargan would protect US officials in Tehran from any violent reactions.

On October 21, Carter caved, authorising the shah’s immediate entry into the United States. In doing so, he failed to consider feasible alternatives that would have been consistent with his values, such as dispatching skilled physicians and medical equipment to treat the shah in Mexico.

Disregarding warnings from Bazargan that he would no longer be able to guarantee the safety of the US Embassy in Tehran, Carter also took no steps to bolster security at the facility or to evacuate all US personnel before admitting the shah. Additionally, Carter failed to grasp the optics of the situation through Iranian eyes — he declined a suggestion from Deputy Prime Minister Ebrahim Yezdi that he allow Iranian physicians to examine the shah, which could have mitigated the popular suspicion that the shah’s arrival in New York on October 22 signalled an American conspiracy to return him to power.

When news of the shah’s arrival reached Iran, the combustible situation predictably detonated. Massive demonstrations erupted in the streets near the US Embassy. “The United States, which has given refuge to that corrupt germ,” Khomeini declared on November 1, “will be confronted in a different manner by us.”

Three days later, a mob overran the embassy, seizing 66 American officials as well as invaluable intelligence information and technology in what the Foreign Ministry labelled “a natural reaction to the US Government’s indifference to the hurt feelings of the Iranian people about the presence of the deposed Shah, who is in the United States under the pretext of illness.”

The embassy takeover provoked a crisis with dramatic political and diplomatic ramifications that echoed for decades. Fifty-two of the hostages would remain in captivity for 444 days, despite Carter’s intense diplomatic efforts, punctuated by an ill-fated military rescue mission in April 1980, to liberate them. Carter’s failure to resolve the crisis doomed his already shaky re-election prospects.

The hostage crisis also strained American-Iranian relations for decades. It generated populist mistrust and hatred in both countries and spoiled prospects of rapprochement between the two governments. While the shah’s Iran had been a reliable US security partner, Khomeini’s Iran became a consistent strategic rival to the United States in diplomatic arenas as diverse as Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Israel. This rivalry contributed to US strategic mistakes such as supporting Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the 1980s.

A few months after the hostages were released in early 1981, Carter explained the logic behind his decision to admit the shah. “I was told that the Shah was desperately ill, at the point of death. I was told that New York was the only medical facility that was capable of possibly saving his life and reminded that the Iranian officials had promised to protect our people in Iran. When all the circumstances were described to me, I agreed.”

Carter’s laboured defence of his decision implicitly acknowledged that he had acted on inaccurate or incomplete information, passively submitting to powerful lobbyists, an inexcusable failure for a president with access to his own information. Carter failed to heed warnings about the broader geopolitical context, or to consider alternative methods to honour his values and assure the security of Foreign Service officers.

We can only hope that Trump and his top advisers will avoid such costly and consequential mistakes in Iran. Failing to certify the Iran deal is not a promising first step.