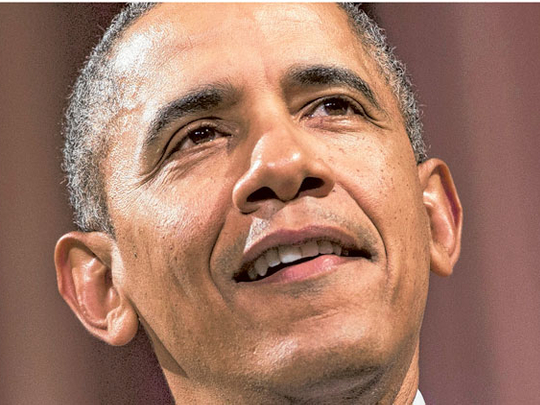

Beirut: US President Barack Obama will probably hear an earful when he meets King Abdullah Bin Abdul Aziz of Saudi Arabia on Friday.

From Iran to Syria and from Egypt to the tacit US support to the Muslim Brotherhood, which Riyadh declared a terrorist organisation, the two men and their advisers will cover the gamut.

Little will be left to chance, as the seasoned monarch will attempt to gauge what motivates Washington under this administration, and whether America’s traditional alliance with Saudi Arabia was no longer valid.

Above all else, the Saudi ruler would want to know whether Obama would satisfy himself by eavesdropping on everyone’s conversations, or whether he may be ready to stand with those who strive to ensure regional stability and guarantee the area’s security.

To say that Saudi-American ties were bumpy under Obama would indeed be an understatement. In fact, if in early 2009 Washington telegraphed a willingness to change the tone of its conversation with the Muslim and Arab worlds after what many perceived to be the difficult George W. Bush years, by 2013, both sides sought to “find common ground and build a common agenda to help shape [a] shared future.”

This search, which presumably updated the oil for security arrangement that was established nearly seven decades ago, highlighted the existence of sharp differences of opinion on several fronts.

To be sure, what changed were the dramatic American shifts in the aftermath of 9/11 as well as the post-2011 Arab uprisings.

In fact, Riyadh was flabbergasted that the United States would abandon a trusted ally like President Hosni Mubarak, a leader it backed for over three decades. Even worse was the way Washington distanced itself from any military retaliation against Syria, after President Bashar Al Assad blatantly crossed Obama’s famous red line, when chemical weapons were presumably used against civilians in August 2013.

Indeed, it was the sum total of these modifications that led Saudi Arabia to walk away from a prestigious UN Security Council seat in October 2013, as King Abdullah voiced his deep frustration with the Obama administration’s policies.

The puzzling mood was reflected in the official foreign ministry statement that clarified why Riyadh could not accept this two-year membership. It pledged that it could not do so “until the Council [was] reformed and enabled, effectively and practically, to carry out its duties and responsibilities in maintaining international peace and security.”

Seldom were Saudi officials as livid, with many privately raising serious doubts about Washington’s commitments to peace and security, even if most public pronouncements couched displeasures in more general terms addressed to the UN. Moreover, senior Saudi representatives maintained that the five permanent Security Council members (US, UK, France, China and Russia) practiced “double standards” for over 65 years, as they failed to find a just and lasting solution to the Palestinian Question.

Other concerns were also cited: neglect towards the establishment of a WMD free zone in the Middle East and, more recently, a nonchalant acceptance of the Syrian killing fields while the world watched.

These were not idle complaints but touched the core of American-Saudi strategic ties that, it was worth remembering, were substantial.

Although the Kingdom’s Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al Faisal reiterated to his American counterpart, Secretary of State John Kerry on November 4, 2013, that “the historic relationship between the two countries has always been based on independence, mutual respect, common interest, and constructive cooperation on regional and international issues to serve global peace and security,” a lot more candour and frankness were recorded instead of customary courtesies.

Remarkably, the seasoned prince reflected the overall mood at the Palace, as the Kingdom graduated from its quietist preferences, and adopted more forceful foreign policy methods.

Even heretofore carefully couched differences among Gulf Cooperation Council member countries were flashed into the public arena as Riyadh pursued specific objectives vis-a-vis Qatar.

Under the circumstances, President Obama was likely to emphasise that Saudi Arabia was not and would not be left alone and that the United States considered the Kingdom to be the essential pivot around which regional stability revolved.

It remained to be determined, however, whether King Abdullah would believe him or, more likely, whether he would forge ahead on a course that emphasised self-reliance.