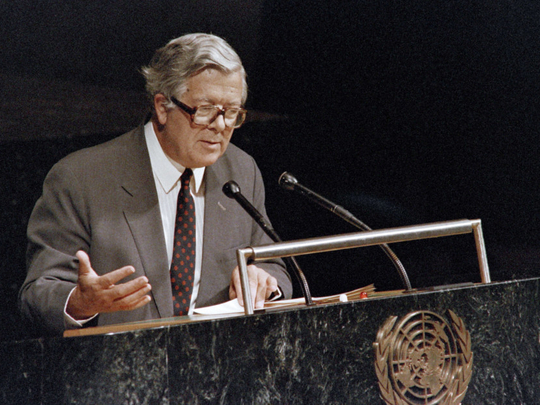

London: Lord Howe, who has died aged 88, served as Margaret Thatcher’s faithful and apparently docile praetor for 15 years, 11 of them as chancellor and foreign secretary, before astonishing the Commons with a resignation speech of such bitterness that it triggered the prime minister’s downfall.

Though never a dazzler — his opposite number Denis Healey famously compared a Howe broadside to being “savaged by a dead sheep” — his ponderous, monotone exterior concealed a subtle wit, a profound legal intelligence and a dogged bravery. Underneath Howe’s mild, avuncular manner lay a convinced monetarist, minded and equipped to implement policies instinctively dear to Thatcher.

As her opposition Treasury spokesman to 1979 and subsequently as chancellor, Sir Geoffrey Howe laid the economic foundations of Thatcherism, with its emphasis on free markets and competition. His first budget, in June 1979, was over-ambitious. The Tories had promised to honour an independent study — by Prof Hugh Clegg (grandfather of Nick) that recommended restoring public-sector pay to levels close to where they were before Labour’s IMF-enforced cuts.

Howe also cut the standard rate of income tax to 30p in the pound. To balance the books, VAT was almost doubled, with inflationary effects, to 15 per cent. Exchange controls were abolished, Thatcher having warned him: “On your own head be it, Geoffrey, if anything goes wrong.”

The next two years saw a much tighter stance on public-sector pay accompanied by factory closures and steep rises in unemployment, as Howe tightened the money supply and allowed exchange rates to rise. In the teeth of a world recession, his 1981 budget was crucial — and much criticised even on the Tory benches. It cut public spending in real terms and — in a severe fiscal squeeze — increased the duty on petrol.

Unemployment rose further and the Conservatives’ standing in the polls plummeted. It proved the turning point for the government’s fortunes. From that day, output and growth began to recover. By his fifth and last budget in 1983, Howe was able to cut income tax once more. Rewarded with the Foreign Office after that year’s landslide election victory, Howe gained a reputation as an unflappable slogger and an effective ambassador for the country.

He was widely seen as Thatcher’s natural successor, particularly were some unforeseen incident to end her tenure. He certainly harboured ambitions to enter Number 10. But his time at the Foreign Office was marked by growing tensions with her, notably over Britain’s relations with Europe. These reached crisis point at an EU summit in Madrid in June 1989 when, with the chancellor Nigel Lawson, Howe forced her to agree to conditions for entering the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) by threatening to resign. Thatcher took her revenge a month later, replacing him with the little-known John Major.

To his subsequent regret, Howe accepted the job of Leader of the House, Lord President of the Council and deputy prime minister. But the move amounted to a demotion. Amid an increasingly bitter atmosphere in Cabinet, Nigel Lawson resigned that autumn; Howe held on but found himself frozen out of the prime minister’s inner circle. He found the Queen asking him about Britain’s decision to join the ERM before he even knew it had happened.

The last straw was Thatcher’s performance at the Rome summit in October 1990, from which she returned declaring “No, No, No!” to closer European economic and political union. He resigned on November 1.

Richard Edward Geoffrey Howe was born into a middle-class Welsh family on December 20 1926. Precociously gifted, he won an exhibition to Winchester. His Welshness in later life was barely discernible. Geoffrey was at Winchester for the duration of the Second World War. He took as little exercise as possible, while developing his keen interest in politics through the school debating society. He also ran the Home Guard signal platoon and — prophetically — a National Savings group. Active too in the photographic and film societies, he would often as a statesman be seen snapping the sights of the world. A fine classicist, he won a scholarship to Trinity Hall, Cambridge.

But first, in 1945, he joined the Army. He was commissioned into the Royal Signals and served in East Africa, where he climbed Kilimanjaro. Going up to Cambridge in 1948, he switched from Classics to Law. His father, a solicitor and coroner, had given him work during his gap year that had stimulated an interest in a legal career. Howe coupled his studies with an active involvement in politics, following what would become the classic post-war route to a Tory seat.

Geoffrey Howe married, in 1953, Elspeth Shand, who enjoyed a distinguished career in her own right and was sometimes reckoned to be the driving force behind her husband’s ambitions. Elspeth Howe was created a life peer as Lady Howe of Idlicote in 2001. She survives him, with their son and two daughters.

— Daily Telegraph