New Delhi: “What address should I write sir? I live on the street!” Rohan says innocently during the Mensa test held in Delhi recently.

The son of a street dweller, he is among the several thousand gifted children from the economically-weaker sections, whose lives are likely to be transformed.

Soon, they won’t hesitate to mention their address.

This is being made possible by Mensa India, a non-profit organisation that holds a qualifying IQ test regularly conducted by certified Mensa proctors.

Those who score in the 98th percentile or above are invited to become members of Mensa India, which is a recognised emerging National Chapter of Mensa International, established in 1948 in England.

Mensa (meaning ‘table’ in Latin) is the world’s largest and the most prestigious IQ society where race, colour, creed, nationality, age, politics, educational or social background are irrelevant.

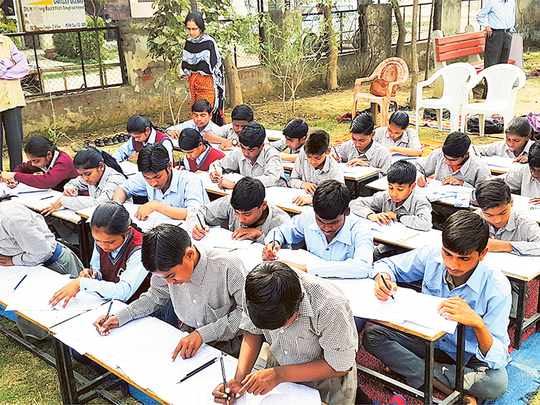

In the past few months, the organisation administered its internationally recognised IQ test to hundreds of underprivileged children in Delhi and NCR. Of the 102 extremely bright children selected, over a dozen achieved an IQ score of 145 plus. The others achieved IQ scores of 130-145, which puts them in the category of “very gifted” children. The average score in Mensa India’s IQ test is between 85 and 115.

Shortlisted from government and NGO run schools in New Delhi and Gurgaon, Haryana, the children, whose parents are labourers, gardeners, rickshaw pullers, street vendors, maids and security personnel, are being mentored under the ‘Dhruva’ initiative, which is Mensa’s Underprivileged Gifted Child Identification and Nurturing Programme.

Catching them young, Mensa has assigned individual mentors to all the gifted children it has identified.

Kishore Asthana, President. Mensa India, says, “It determines their strengths and weaknesses and delves into the vocations the children are likely to excel in. Incidentally, a lot of these children are unaware of their extremely high IQ.”

Figures from the 2011 Census show India has about five million underprivileged children with high IQ. Many of them desire to become scientists and doctors, which is bound to change the course of their lives. But if their intelligence is not recognised and remains unutilised, it can be a waste of the nation’s intellectual resources.

Asthana cites the case of 14-year-old Varsha, a Grade 7 student, who has three sisters and a brother. Studying in Government Senior Secondary School in Chakkarpur, Gurgaon, she scored in the 99 plus percentile in the IQ test.

Asthana says, “This is our highest rating and denotes an IQ above 145. But we were shocked when one day she suddenly stopped coming to school. Varsha’s mentor informed me that her parents had dissuaded her to study further and that she had taken up a job!”

The director immediately decided to meet Varsha and her parents at their 2.74-metre x 3.65-metre single room tenement.

“Her father, a 65-year-old construction worker-turned-security guard said that he was jobless because of a salary dispute with his employer,” Asthana says. “Varsha’s mother, also a construction worker, had hurt herself when accidentally bricks fell on her head at a construction site and was unable to work.

“The money that the parents had saved soon dried up and the family was on the verge of starvation.

“Seeing her parents and siblings suffer, the sensitive girl had decided to shoulder the family responsibility by taking up a job that involved looking after two small children 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Varsha was not sure how much salary she would get, but said she had asked for Rs8,000 [Dh432] a month.”

The bewildered director asked the young girl if she realised the danger she was getting into.

“I couldn’t imagine a child herself looking after two children, who could get hurt. But it was not easy to change Varsha’s mind, as she had decided to earn money for the family,” he said.

Mensa India has a small fund, which it sets aside for such emergencies. Asthana offered to pay Varsha’s family Rs5,000 monthly until such time as her parents got steady jobs and she would continue with her schooling. That apart, if any emergency arose, Varsha could contact him. At the same time, it was made very clear to her parents not to become dependent on that handout on a permanent basis.

The organisation arranged a cleaning job for Varsha’s mother in the vicinity of the coaching centre, where Varsha was provided free tuition to hone her skills further.

The official went to the extent of counselling her father and met his employer, who not only took him back, but also raised his salary. The family has now become independent.

Mensa operates from Delhi/NCR, Mumbai, Chennai, Pune, Bengaluru, Kolkata and Hyderabad. It’s future plans include expanding to smaller towns and cities. It conducts aptitude tests to determine the strengths and weaknesses of these children, referred to as Mensa scholars. In addition, they are helped in vocations of their interest, so that it becomes easier for them to realise their dreams.

Asthana explains, “Even though many of these students get good grades, not all are top performers at school. The Mensa test measures the child’s potential and what he or she is likely to become, rather than their present academic performance. These children smile when they are told about their high IQ. The puzzled look on their faces tells that they have never been told they are intelligent. We intend to constantly tell them that they are bright and smart, despite having disadvantaged lives and that they can be the change for themselves.

Aditya, studying in Grade 8, had his own issues. The 14-year-old’s parents were separated and his mother single-handedly looked after Aditya and his sister. The mother works as a maid in the school. Aditya, with an IQ above 145 desires to become a pilot.

Asthana informs, “One day, I met his mother and told her to feed her son properly, as he was very lean and looked undernourished. She complained that he did not eat after coming back from school. Aditya disclosed that his mother cooked food in the morning and it would get cold. But she never allowed him to reheat it, as she said cooking gas was very expensive.

“It was difficult for the family of three to survive on a monthly income of Rs6,000, out of which house rent, etc had to be managed and there was no money left for luxuries such as hot food. She also mentioned she was paying Rs1,000 towards tuition fee for both her children.”

Mensa agreed to pay the tuition fee on a condition that Aditya was allowed to reheat his food. Aditya now looks quite healthy. “I eat 6 rotis (Indian bread) now,” he grins.

Asthana implores people to look for and report such young minds and if possible, assist them in approaching mediums like Mensa. Its standardised tests are created by Pune’s Jnana Prabodhini Prashala. The tests use less text and more graphics. However, Mensa’s tests can also differ from country to country.

Even though the organisation does whatever best it can, not all stories have a happy ending. The official mentions 12-year-old Babita, who studied in a roadside school held under tarpaulin sheets. The Grade 6 student scored 99 plus in Mensa’s IQ test. This was especially creditable, as her father had died at a construction site just two months before her test. Her mother looked after Babita and her sister by selling tea in a slum cluster where they lived.

Then, as in some other cases, Babita stopped going to school. The Mensa official rushed to her home, only to find that Babita’s mother had decided to go back to Malda in West Bengal, where they originally came from.

The authorities had demolished the slum cluster in which they lived and the dwellers had no roof over their heads. He implored the mother to stay back for the sake of her daughter, assuring her a secure job and a house and changing their entire life for the better. But that demolition had as if broken her spirit, she refused to stay back and left for Malda.

Asthana said, “I had even given her the choice to go to Kolkata instead, so that we could arrange for Babita’s studies there. It didn’t move her. With deep regret I remember Babita’s brilliance wasted. She was an ever-smiling child. I even gave her my phone number, asking her to contact me if she came to Kolkata or Delhi. I am hopeful that one day I will hear from her.”