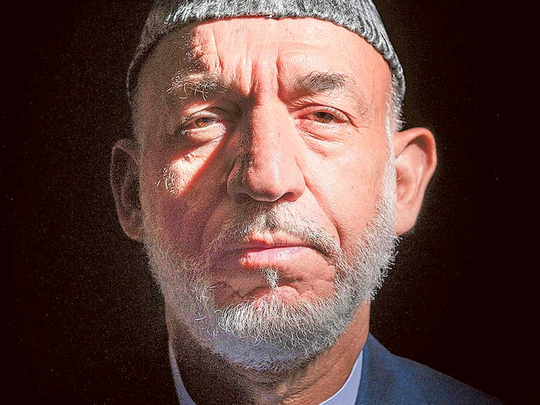

Kabul: Hamid Karzai, the former Afghan president and current antagonist to his successor’s government, likes to describe Afghan politics as a marathon.

To the long roll call of visitors he meets each day — regional power brokers and elders, government officials, religious leaders, well-wishers who reminisce longingly about his years in power — the metaphor is clear. Karzai has never stopped running, never stopped manoeuvring, and he won’t.

Karzai’s critics, especially those close to President Ashraf Ghani, accuse him of working from the wings to destabilise the government and exploit a moment of national crisis to try to return to power — or at least to force some concessions. They say Karzai is actively undermining a vulnerable president, maintaining an alternate pole of political influence and patronage, and stoking protest movements that some fear could turn violent.

So what is Karzai’s answer? He flatly denies that he is trying to harm the government. But then there’s the hint of a wry smile: “If there are some people running faster, those who are falling behind should not complain.”

Following Karzai through days of meetings — dozens of discussions, and interviews on and off camera — it becomes clear that he is still operating like a man in power.

His many visitors come to seek his leverage in the government, and he is happy to pick up the telephone to call a minister, a governor or an ambassador. He still communicates with world leaders, signing letters to them on a weekly basis.

Much of Karzai’s politics happens around noon, when a larger crowd gathers for a group prayer on the grass outside and then follows him upstairs to a sunlit dining table for lunch. On a given day, there are former and current government officials, generals, judges, bankers, tribal elders, former members of the Taliban and preachers from Kabul’s major mosques.

He seems to invite the question hanging over him: If Karzai does not want to return to power, just what is he trying to achieve by increasing pressure on a government already on the brink?

And it is on the brink. In private conversations, Afghan and Western officials alike worry Ghani’s administration could be facing an existential crisis that could peak as soon as next month.

The end of September is the deadline for the government to meet the commitments of a political deal brokered by US Secretary of State John Kerry after the catastrophic 2014 election dispute. By then, Afghanistan is supposed to hold parliamentary elections, enact sweeping electoral reforms, and amend the constitution to create the position of prime minister for Ghani’s election rival and current governing partner, Abdullah Abdullah. But staying on schedule was already impossible many months ago, and Kerry has publicly insisted that Ghani’s government will remain through the end of its five-year term, regardless.

That is just the beginning. The country’s security situation is worsening, despite the US military’s increased involvement in the fighting. The Taliban have seized many districts, and they threaten to take many more.

Ghani, the constant technocrat, has been forced to focus on security, and his economic initiatives have stalled. And suddenly he has also been challenged by a street protest movement in which ethnic Hazaras are accusing his government of systematic discrimination.

The most recent of the demonstrations was struck by a suicide bombing, claimed by Daesh, that left at least 80 people dead. Now the demonstrators accuse the government of purposely leaving them vulnerable to attack, and they have given Ghani an ultimatum to meet their demands — another September deadline, as it turns out.

On top of all that, a new protest movement, potentially more dangerous, is growing just north of Kabul, the capital, calling for the government to rebury with dignity a northern bandit king who has been dead for nearly a century, shot by a firing squad. Among the people calling for the reburial, and threatening protests, are northern militia commanders who have long been sceptical of Ghani, and they have also given him a September ultimatum.

Government officials accuse Karzai and his allies of having a hand in the recent protests. But he says he is after neither the collapse of the government nor a return to power. “I have absolutely no doubt about that,” he said.

He just wants the government’s legitimacy affirmed after the September deadline, he said, and the only way left is to call a traditional loya jirga — a grand assembly of tribal elders from across the country.

Karzai’s push for a loya jirga is the move most widely seen as a game plan for returning to power, or at least for negotiating more leverage. His strength is with the tribes and the power brokers he has maintained at his side, while Ghani has alienated many of them.

It helps to understand that Karzai represents an entire network of power — national as well as local — accumulated over 13 years and beyond. That network feels that it is slowly being uprooted under Ghani’s presidency, and that it could be vastly weakened if the current government survives the September deadline intact.

In Kandahar, powerful strongmen who owe their rise to Karzai’s protection have had standoffs recently with officials sent by Ghani over lucrative custom taxes and where the money goes. A northern lawmaker who stopped by to see Karzai complained that the government was cutting her off and working “so beautifully and systematically” to weaken their mutual support base. She might not return from vacation abroad, she said, if the situation continued and Karzai did not signal his plan clearly.

If it came to an open political struggle, it is unclear whether Ghani would be able to score points with what would be perhaps his best case to make against Karzai: that the seeds of the current security and political crises were sown on Karzai’s watch, and that the former president left him a system suffocating in corruption and patronage.

That is in part because Karzai has been busy using his social acumen to try to shed a more favourable light on his legacy after 13 years in power.

Karzai, who lives a stone’s throw from the presidential palace, says his routine has changed little since he was president. He has more free time to relax in the afternoons, but his mornings are busier. He meets more people than he did when he was in power. On average, his office estimated, Karzai sees more than 400 people a month. Every Eid, three-day Muslim celebrations that come twice a year, Karzai opens his gates to a flow of visitors, reaching up to 6,000 people.

From the moment he leaves his residence in the morning, his two young daughters tugging at his trousers, he is a man on the move, trailed by secret service agents. Karzai, 58, describes himself as hyperactive, and he is rail-thin. He drinks four or five espressos a day.

He still moves with ease among drastically different groups of people, from Oruzgan elders who interrupt him with passionate diatribes, to groups of youths coming to present him with their latest research.

Karzai makes them laugh, and when they shed tears, as one group visiting from central Afghanistan did during a recent audience, he offers tissues.

As for what he might be seeking from all of this, Western officials in Kabul acknowledge that Karzai, a masterful tactician and politician, does not necessarily need to have a clear concept of what he wants. He can mount pressure on the government in ways big and small, throw many irons in the fire, and perhaps force a critical blunder from Ghani.

But Ghani is not without resources. Much will depend on how many opposition figures the president can co-opt to keep Karzai at least partly on the margins.