Washington: Tom Hayden, a 1960s radical who was in the vanguard of the movement to stop the Vietnam War and became one of the nation’s best-known champions of liberal causes, has died in Santa Monica after a lengthy illness. He was 76.

Hayden vaulted into national politics in 1962 as lead author of a student manifesto that became the ideological foundation for demonstrations against the war.

President Nixon’s Justice Department prosecuted Hayden in the raucous “Chicago 7” trial following the violent clashes with police at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

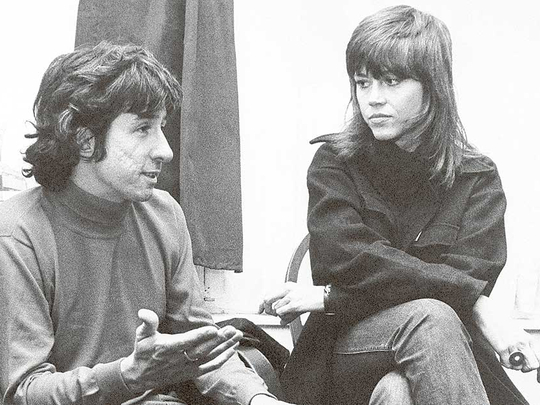

Hayden later married actress Jane Fonda, and the celebrity couple travelled the nation denouncing the war before forming a California political organisation that backed scores of liberal candidates and ballot measures in the 1970s and ‘80s, most notably Proposition 65, the anti-toxics measure that requires signs in gas stations, bars and grocery stores that warn of cancer-causing chemicals.

Hayden lost campaigns for US Senate, governor of California and mayor of Los Angeles. But he was elected to the California Assembly in 1982. He served a total of 18 years in the Assembly and state Senate.

During his tenure in the Legislature, representing the liberal Westside, Hayden relished being a thorn in the side of the powerful, including fellow Democrats he saw as too pliant to donors.

“He was the radical inside the system,” said Duane Peterson, a top Hayden adviser in Sacramento.

A longtime target of government surveillance, Hayden took pride in his history of dissent. A photo from the late 1970s shows him pondering, with apparent satisfaction, his 22,000-page FBI file, stacked about 5 feet high.

After the deadly 1967 riots in Newark, New Jersey, where Hayden had spent several years organising poor black residents to take on slumlords, city inspectors and others, local FBI agents urged supervisors in Washington to intensify monitoring of Hayden.

“In view of the fact that Hayden is an effective speaker who appeals to intellectual groups and has also worked with and supported the Negro people in their programme in Newark, it is recommended that he be placed on the Rabble Rouser Index,” they wrote.

Hayden’s charisma, drive and intellectual heft made him a potent force. “Tom had the gift of articulating the larger meaning of smaller events,” said Todd Gitlin, a writer who succeeded Hayden as president of Students for a Democratic Society, a flagship organiser of 1960s protests. “He was very crisp and clear and unlikely to be at a loss for words as a public voice.”

Freedom Ride group

Hayden, who relished media attention and was skilled at attracting it, worked closely with militant radicals but was equally at ease with the likes of governors and presidents. “He’s always been someone who would much prefer to work and get things done than stand on the sidelines and protest,” Fonda once said.

Born on December 11, 1939, Hayden grew up in middle-class Royal Oak, Michigan, a Detroit suburb. His father, John Hayden, was an accountant at Chrysler; his mother, Genevieve Garity, was a film librarian at local schools.

At the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Hayden was editor in chief of the campus newspaper and was captivated by the burgeoning civil rights movement in the South.In 1960, he hitchhiked to California to cover the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles, where John F. Kennedy was nominated for president.

Soon after, Hayden made his first journey south for civil rights work, driving to rural Tennessee with fellow students in a station wagon packed with clothing and food for black sharecroppers who had been evicted from their homes after registering to vote. Hayden returned to the South in 1961. He and a friend were beaten and arrested at a civil rights march in McComb, Mississippi, in a rural area where few blacks dared to vote.

On his 22nd birthday, Hayden was arrested again in Albany, Georgia. He’d been in a “Freedom Ride” group of black and white students who, on a train from Atlanta, ignored an order to leave the “white” car, then got thrown in jail for blocking the sidewalk upon arrival in Albany.

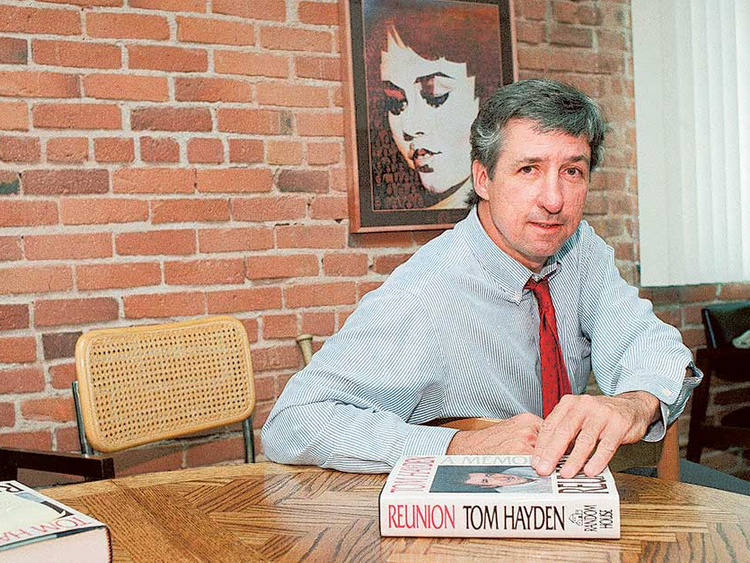

“To those who did not pass through the Southern civil rights experience, wilfully going to jail may seem like a career-threatening act of despair,” Hayden wrote in his 1988 memoir, ‘Reunion’. “It was not. It was both a necessary moral act and a rite of passage into serious commitment.”

In 1962, Hayden joined dozens of other students at a Students for a Democratic Society convention in Port Huron, Mich. As primary author of the group’s Port Huron Statement, he gave voice to a youth disaffection that foreshadowed the explosive power of the anti-war and civil rights protests of the years ahead.

“We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit,” the manifesto began.

Inspired by sociologist C. Wright Mills and French author Albert Camus, among others, Hayden and his fellow students bemoaned poverty, racial bigotry, the Democratic Party’s tolerance of Southern segregationists, the threat of nuclear war and an apathetic citizenry. They called for mobilising students and like-minded Americans through “participatory democracy.”

“If we appear to seek the unattainable, as it has been said, then let it be known that we do so to avoid the unimaginable,” the statement concluded.

Eyewitness complaints

Before long, the Vietnam War, the draft and violence in the civil rights struggle darkened the nation’s mood and opened sharp racial and generational divides. In Newark, Hayden collected eyewitness complaints as police and National Guard troops waged street battles for six days in the impoverished neighbourhoods where he lived and worked. Twenty-six people were killed.

More and more, Hayden focused on opposition to the war — “this slaughter of a distant people,” he called it.

“From the very beginning, Tom played a visionary role in developing strategy for the anti-war movement,” said Bill Zimmerman, a Santa Monica media consultant who was close to Hayden.

Gradually, Hayden’s activism became focused primarily against the war. In 1965 he travelled with an anti-war group to Hanoi, the capital of communist North Vietnam. The 10-day trip offended many in the US, and the State Department temporarily withdrew Hayden’s passport.

He returned to Hanoi in 1967 with another anti-war delegation during a period of heavy US bombing. Hayden, wearing a helmet, was forced at one point into a ditch and worried a US bomb would kill him.

THayden paid a personal price for his work as a radical.

His father, a Republican, refused to speak with him for 13 years. They reconciled before his father’s death, a few days before Hayden won election to the Assembly in 1982.

A prolific author, Hayden wrote books on Cuba, Ireland, Vietnam, street gangs, spirituality and environmental protection, the Iraq war and the Newark riots.

Hayden is survived by his wife, Barbara Williams, an actress and singer; their adopted son, Liam; Troy Garity, his son with Fonda; and his sister, Mary Hayden Frey.