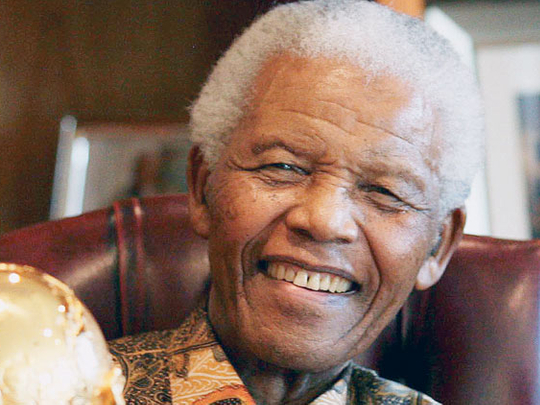

Dubai: Before journalists and photographers meet Nelson Mandela, his press aides make one polite request: “No flash, please.”

It’s not that this lion of south Africa is a vain man — nothing could be farther from the truth — it’s because his eyes are forever damaged from breaking rocks in the hot sun day after day in the white limestone prison quarry on Robben Island where he was imprisoned between 1964 and 1982, and thereafter at Pollsmoor Prison in nearby Cape Town until his eventual release in 1990.

It says a lot about a man that he can grasp the conscience of the world by the neck from a prison cell, that he could force an end to the apartheid regime of South Africa, that he could make peace and build a new nation forged between Blacks and Whites.

When he was born, the First World War was still raging across the fields of Flanders, the Bolsheviks still months from their workers’ revolution in Russia, his native Transkei a sleepy province of South Africa, still trying to come to terms with British rulers who had inflicted the horrors of the first concentration camps on the Boers.

His father, Chief Henry Mandela of the Tempu tribe, instilled in him a love of justice and law and it was that kindled his life’s struggle against apartheid — morally repugnant, racist, institutionalised bigotry and state-sanctioned eugenics.

When the Second World was still raging, he joined the African National Congress, promoting the radical thought that all South Africans are created equal, have rights to justice, education, houses, a share of the wealth of the richest nation then on the continent, and that South Africa itself should be an independent nation free of intolerance — radical, dangerous and socialist political ideologies.

When the National Party institutionalised racism with its apartheid policies in 1948, Mandela was transformed from a mere activist into the more dangerous person — one who used the knowledge of the law to undermine injustices, representing those arrested in the struggle in the white man’s court.

In 1956 he was charged with treason — daring to plot and bring about an end to white rule — but he was acquitted in 1961. A year earlier, his ANC was banned, an illegal and immoral organisation for acts of violence and words of equality against the rule of racist hate.

But it was he who argued for the setting up of a military wing, for the use of armed force against the regime: minority rule of the white man could only be brought about with a Kaleshnikov in one hand, the other on a political movement that sought to internationalise the struggle against apartheid.

It was a dangerous course for South Africa — the ANC leadership finally agreed. The formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the military wing of the ANC, fighting with its borders and using external — mostly Soviet support from neighbouring countries.

Mandela was arrested in 1962 and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment with hard labour. In 1963, when many fellow leaders of the ANC and the Umkhonto we Sizwe were arrested, Mandela was brought to stand trial with them for plotting to overthrow the government by violence. His statement from the dock received considerable international publicity. On June 12, 1964, eight of the accused, including Mandela, were sentenced to life imprisonment.

There’s an irony that can’t be overlooked in that Mandela — a Nobel Peace Prize winner with William de Klerk in 1993 — was a committed fighter, willing to use force and violence for political ends. But if ever violence for political ends is justified, then Mandela’s cause is such, given the state-sanctioned torture and shootings, abuses and deaths committed by the apartheid regime.

But the irony is that his imprisonment galvanised the conscience of those who sought and end to the policy of apartheid, either in sporting isolation, international boycotts, sanctions and castigation by the global community.

As with the fall of the Berlin Wall or the attacks of 9/11, people know where they were when Mandela was freed — when South Africa voted for the first time — millions lining up as equals, black and white together to cast ballots in free and fair elections.

He is a lion, a giant of our times, unrivalled for changing a world of coloured choices. Sadly, we will all remember where we will be when he passes. We should be proud to say we knew him, however little, however large, however influential.