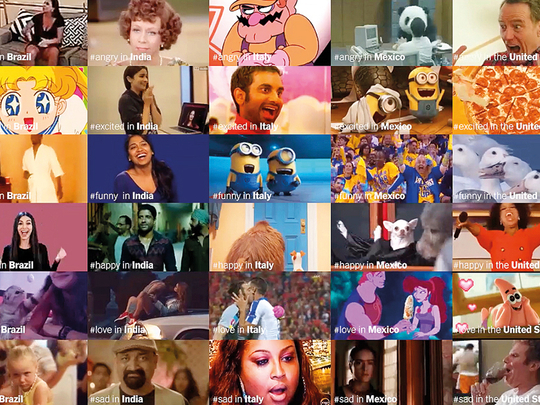

Washington: The Graphics Interchange Format (gif) — just long enough to convey a single emotional gesture, and simple enough to cross linguistic and cultural barriers — has marched to the front line of online expression around the world. And Giphy, the first and largest gif search engine, has become an international clearing house for the form since its 2013 launch. It’s a site where gifs are created and uploaded and then catalogued by emotion, demographics and cultural reference points. Using data provided by Giphy, we’ve been able to identify how people in Brazil, India, Italy, Mexico and the US express seven basic feelings through gifs.

There are certain gifs — the close-up clip of a mildly-offended man that went viral as the Blinking White Guy meme, for instance, or a remixed image of a crying Michael Jordan — that enjoy great circulation everywhere.

What we’re interested in is where global gif culture diverges, and where local vernaculars emerge. We found that by looking at the relative popularity of each gif by country. The resulting matrix shows us the most American way to express happiness; the most Italian way to show love; the most Indian way to say you’re sad.

As we survey gif usage around the world, what pops out is how people from different countries draw on a globalised media ecosystem to express themselves online. Minions, the nonverbal sidekicks from the animated blockbuster Despicable Me, were created by Hollywood to appeal to moviegoers worldwide. Now they’ve seamlessly worked themselves into the online culture, too — they’ve become a top avatar for Italian gif users to express humour, and for Mexican users to express excitement.

There’s also plenty of cultural drift on display. The gif’s transcendence of language means it skips easily over national barriers. One of Mexico’s favourite ways to express anger is from a viral 2010 commercial by an Egyptian dairy company called Panda Cheese that features a panda wreaking havoc on an office. Another popular gif in Mexico was captured during the NBA playoffs as two fans of the Golden State Warriors danced in the stands. (It’s now a visual stand-in for expressing laughter.)

Meanwhile, a clip of Aziz Ansari caught in a moment of wide-mouthed glee (from the now-departed sitcom Parks and Recreation) has gained traction in Italy, and an image spliced from the Japanese manga series Sailor Moon has caught on in Brazil.

The results also speak to the complexities of cultural appropriation. Mexican gif users have taken the Hollywood version of their national icon, Frida Kahlo, and recast it as a culturally specific way to express sadness. And Italian users have adopted Wario, the villain of Super Mario Bros., as a conduit for their anger. So a game about cartoon Italian people created by the Japanese designer Shigeru Miyamoto has become an emotional outlet for actual Italian people.

There are canny cultural adaptations at work, too, like the popular Mexican love gif that takes a clip of Hercules (as depicted by Disney) presenting a white flower to his love interest, Megara, and replaces it with a cob of Mexican street corn.

Some of these gifs come from unrecognisable sources (none that we recognise, at least). They’re cut from amateur videos that are quickly converted into the texture of the web, living on as popular gifs without otherwise elevating their subjects to internet fame.

Other gifs are the product of Giphy itself, with an eye toward creating new images that seem primed to catch on online. We’re now seeing the rise of gif-native stars — actors and Giphy staffers enlisted to enact emotional expressions such as laughter or shade — as well as Gif artists recruited to draw original emotional loops into existence.

Internet-savvy companies are capitalising on the medium, too, turning gifs into micro-ads that percolate around the web. Like the branded gif from Papa John’s Pizza, which has become a top expression of excitement in the US.

The subjects of gifs tend to gravitate toward cultural extremes. In India, that means the satirical spectacles produced by the YouTube comedy group AIB. Many of the country’s most popular gifs are spliced from its skits.

Italian gif users mine the drama of the football field, elevating the image of the Italy players Giorgio Chiellini and Gianluigi Buffon celebrating into a top Italian expression of love.

And in Brazil, the gif-iest celebrity is Gretchen, a ubiquitous fixture of the country’s pop culture who has variously been a pop star, an adult film star, a mayoral candidate and a reality TV fixture.

Gretchen has recently enjoyed a brush with international internet fame. In March, Nicki Minaj tweeted of her, “Man can someone tell me WHO this lady is?!?!! This lady been in EVERY other GIF for like the last 6 months.”

Gabriela Lunardi, a Brazilian meme researcher, puts Gretchen in the context of Brazilian internet culture writ large, writing that promoting a figure such as Gretchen to the outside world is a means of both “recognising ourselves as a nation” while “criticising our problems through humour”. Gretchen is simultaneously a source of pride and a laughingstock.

That ambivalence is baked into the gif’s culture-defining power.

The local icons selected for heavy gif-ing can reflect points of national identification — a clip of Will Ferrell crying into an oversized glass is a top sad gif in the US, for example — but they can also reveal troubling truths about national attitudes about gender and race. Women are often smeared as overemotional wine-guzzlers, and black people pigeonholed as perpetual performers whose emotions are always cranked to 11.

In America especially — but elsewhere, too — women of colour are called on disproportionately to express extreme emotions on behalf of gif users: A hyper, sped-up clip of Oprah caught in a “AND YOU GET A CAR!” moment is a top American happy gif, while a reaction shot of Tanisha Thomas crying on the US reality show Bad Girls Club has gained traction in Italy as a way to express sadness.

When people around the world drop a gif in a chat room or channel, they’re often just trying to express how they feel. But they’re also revealing their cultural pride and shame, their obsessions and their biases. The gif works as a kind of cultural instant replay: We’re invited to watch them over and over again until the smallest moments loom large in the culture — for better or worse.