"What theatre can provide — in a way that no other artistic medium can — is a full sense of human presence," says Michael Boyd, the artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company. "If it is going to succeed in the future, it needs to celebrate the fact that audience and performers share an experience in the same space at the same time."

It is a rallying cry with profound implications, not just for actors and directors but for architects too.

The RSC's base recently reopened in Stratford-upon-Avon following three and a half years of remodelling. This is a project of dizzying intricacy — the product of highly taxing technical and conservation constraints — and not everything about it succeeds; but Boyd's vision of the future of theatre shines through vividly.

The latest change

Designed by Bennetts Associates, it is just the latest in a line of remodellings that the Royal Shakespeare Theatre has undergone since its foundation in 1873. The original building presented a fantasy of Ye Olde England, complete with neo-Tudor half-timbering. Its focus was a 32-metre water tower that loomed over the town and was intended as a safeguard against fire.

In 1926, however, the tower and a significant part of the building it was meant to protect burnt to the ground.

A competition was quickly held to find a design for a new theatre. Elisabeth Scott, one of the very few women architects working in Britain at the time, won it with a design for a 1,400-seat auditorium, which backed directly against the retained ruins of the Victorian building. Its layout was indebted to her experience as a designer of cinemas. Intimate it was not.

The original similarity

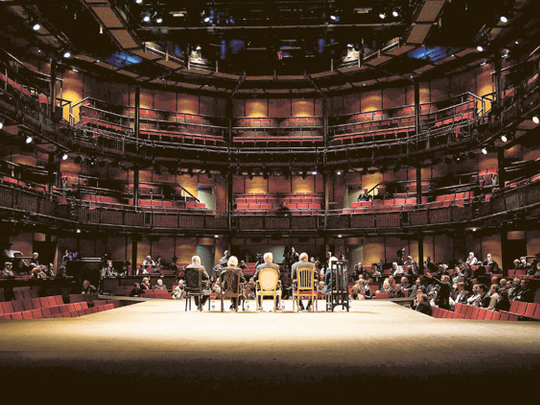

In 1986, a second house was established within the still-standing shell of the Victorian building. This was the Swan, a venue that offered about a third of the capacity of the main auditorium but proved more popular with actors and audiences alike. Key to this was the fact that it employed a projecting "thrust" stage — an arrangement similar to that on which Shakespeare's plays were originally performed. This configuration presented major challenges — set designers had to find ways to populate the stage so as to avoid obstructing the audience's view while actors had to move so as not to keep their backs to any part of the audience for too long. And yet, the theatrical charge that could be generated by bringing the audience and the performers into the same space more than compensated for those limitations.

Ever since, the RSC has harboured a desire to exchange the Scott auditorium for a venue of equivalent capacity but of a layout much closer to that of the Swan. And the new auditorium is a triumph. It shows every sign of living up to Boyd's billing of it as "the best place for performing Shakespeare in the world". In the new theatre, the actors can make eye contact with virtually everyone in the audience.

Lessons learnt

The architects enjoyed one luxury during the design process: The temporary Courtyard Theatre, which the RSC constructed to allow it to continue performing, served as a full-scale prototype. Important lessons were learnt from the Courtyard that informed the design of the new space, particularly those in relation to acoustic performance.

The most significant difference between the two venues, however, is their back-of-house provision. The Courtyard scarcely has any space above or below its stage. The new theatre not only has a seven-metre fly tower but a seven-metre basement to boot. The Forest of Arden can now be summoned at the press of a button. Beyond the auditorium, the results are more mixed. The new public spaces are generic — the palette of grey painted steelwork and full-height glazing serviceable but distinctly underimagined.

However, the more significant misjudgment is the one moment where the architects have allowed themselves a truly emphatic gesture.

On the site's most prominent corner, a new tower has been constructed of a height that matches the long-vanished water tower. One can see the logic. The old building's primary orientation was to the river, with the effect that it turned its back on Stratford — a failing that has now been corrected through the creation of a much-expanded lobby running the full length of the town elevation.

Tower of observation

The tower stands sentry-like beside the new front door. The architects talk of it as being wedded to the Italy of Shakespeare's imagination. And yet, this is not a campanile but a startlingly imposing structure designed for the purpose of observation.

Visitors can take a lift to the top and, on a good day, can see four counties. It is a nice view but the cost of providing it has been the transformation of a large part of the town centre into Stalag-upon-Avon.

These frustrations aside, the RSC at last has a venue that might actually aid its work rather than impede it.

"We live in a world where we are less social. We entertain ourselves in too lonely a way," Boyd says. The new theatre has been conceived as a counter to that bleak scenario — a celebration of togetherness.

The first production specifically designed for it opens in April 2011. I'll see you there.