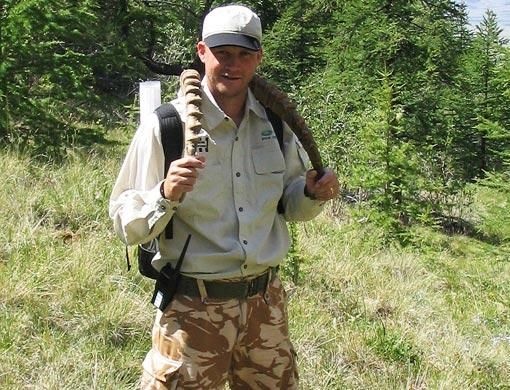

Growing up in rustic Bavaria, Matthias Hammer loved nothing better than observing the wildlife in the woods next to his home.

His dream was to be a field biologist, and he worked hard. As a biology doctoral student at Cambridge and Oxford universities, Hammer organised and helped run several expeditions to the Amazon, Madagascar, the Caucasus, the Alps and the Rocky Mountains.

But an uneasy relationship with his tutor put an end to Hammer's university aspirations, and put him in touch with his life's work. Disillusioned by ivory-tower academia, Hammer founded Biosphere Expeditions in 1999 so he could indulge his love for the outdoors while continuing to work as

a scientist.

Hammer, a vegetarian father of three, has led teams all over the world. He is a qualified wilderness medical officer, ski instructor, mountain leader, dive master and survival

skills instructor.

Biosphere Expeditions has helped save wolves in Poland, snow leopards in the Altai, puma in Peru, and whales and dolphins in the Azores, to name a few.

Anyone can be a part of the expeditions and help conservation scientists – from 80-year-old grandmothers to three-year-olds.

Hammer's work is proof that everyone can make a difference, irrespective of their background, fitness or age. He encourages participation from all walks of life with the common aim of seeking adventure with a conscience and a sense of purpose.

"I wish more people understood their personal impact on the world, and the consequences of their actions on the forests and wildlife," he says, adding, "It's crucial."

I

I think my most inspiring conservation story was how we prevented the culling of wolves in Poland. It wasn't only our efforts, but our data definitely helped. The reward was immediate and obvious – the wolves were saved from being killed because of our work.

I would like to have more patience and wisdom. Bureaucracy can be the most frustrating part of my job. I find it infuriating.

I don't take holidays because my life is a holiday. I love my work. I don't need to do package tours. Over the years,

my job has got better. I learn more, get to meet different people and travel extensively.

I have learnt that less is more. I hope my children will learn that the best playground is the woods, not the latest plastic toys.

I most admire the participants who go out of their comfort zone to participate. For many, going to the Altai or Oman, staying in a camp for two weeks and roughing it out in the wilderness, is a big step.

Recently, we had one guy who was afraid of heights, but overcame that fear to go up and down the mountain and complete the surveys. Such people inspire me.

Me

Me and my childhood dream

I had a sheltered, traditional childhood, and was very close to my paternal grandmother. My grandfather was a lawyer.

My parents belonged to the post WWII generation; neither of them went to university, but they always supported what I did.

I appreciate that. Growing up, I didn't want to be an astronaut or a fireman. I always wanted to do field biology ever since my father first took me to the woods.

We would look at badgers and squirrels, and he'd tell me about the trees.

In Germany, I grew up watching Heinz Sielmann on TV, the German equivalent of David Attenborough.

His shows about expeditions to Africa made me want to be like him. I thought the way to do this was to become an academic. My life plan was to become Professor Hammer and research beetles in the jungle or something like that.

I spent hours, sometimes days outside, watching the animals in the field or watching birds through a pair of binoculars. Ours was the last house in the village, just beyond were the woods.

The only parental ruling was that I had to be home before the streetlights came on. I finished school and joined the army at 18, serving for five years with the German Parachute Regiment.

Me and becoming an academic

My life has been steered by women – first my mother and grandmother. We had a large house, and my mother invited foreign students to spend the summer in Bavaria. O

One of the students who came over one summer was English, and she suggested I apply to Oxford or Cambridge because I had good grades. She helped me fill in the forms for Oxford, and I got a place.

After my stint with the army, I left for the UK to be educated at St Andrews, Oxford and Cambridge.

I organised expeditions in Oxford and Cambridge – a kind of tradition there. I loved doing it because I had the organisational as well as the leadership skills developed from my army life.

But I didn't get on particularly well with my supervisor. We were polar opposites! I was into sports and field work, he wasn't. He was a Cambridge professor and made me realise that once you get into academia, it was just a lot of pen pushing.

I'd meet with him to discuss my thesis, and there would be phone calls about a gas leak in the lab or grant proposals to be filled in.

That's when I had a moment of crisis. After years of study, becoming a professor was really not what I imagined it to be! I didn't want to end up like that.

This is where another woman comes in. My girlfriend at the time suggested I take people out on expeditions and get them to pay for it.

Recalling that moment gives me goose bumps even now. I remember it as if it was yesterday. Some people talk about having had revelations – a solution to a problem that comes out of nowhere. I visualised Biosphere as it is today in that moment.

It was such a clear vision of what I was going to do. It was an amazing experience.

Me and setting up Biosphere

In 1998, I finished my PhD and looked into voluntourism. I found there was a small market for it. There were a couple of organisations doing this.

I thought there had to be more people who wanted to do something with their holiday time other than sitting

on the beach.

In the UK, they are very supportive of entrepreneurs. I had no idea about book-keeping, PR or marketing, but the government trained me for free.

I did the course and took the plunge based on the few contacts I had made at university. Ten years later, we've had 10 projects worldwide and won quite a few awards.

In the beginning it was just a two-man show. I led the expeditions myself. I approached the scientists. Now my role is more managerial, although I still get to travel a lot. I can cherry-pick the best projects! We have staff members in charge of expeditions, and scientists approach us for Biosphere volunteers.

We get up to 50 requests a year.I have three children – Liesl, 6, Lukas, 5, and Sophie, 3. Our children travel with me too. When our first-born was barely six months old, I took her to Ukraine. This year they'll come with me to Namibia. My children love camping and sleeping in the open.

Our global sponsor, Land Rover, helps us reduce our running and expedition costs by providing the LR3 vehicles for the teams. This allows us to divert our funds into the projects and people, and to take our conservation expedition to some remote and inaccessible terrain.

Joining us on an expedition is as easy as registering and paying the deposit online. The way this works is that participants help on two levels – through labour and money. This in turn allows the expeditions to run.

We split them into one- or two-week slots. We're very proud of our scientific outputs. For me personally, it's the best of both worlds. I still publish all the research and results from the expeditions, putting my skills and training as an academic to good use.

I am still working as a scientist, without being an expert in any one species.

Myself

Is there a danger in focusing on charismatic species such as leopards and whales when we might not be able to save the lesser-known or not so photogenic species?

We need a flagship species, something that excites people. We could do a scientifically valuable expedition on termites, but nobody would come. Our portfolio has species that get people fired up – such as whales and leopards.

You need to capture people's imagination. If you can get a habitat protected because of the flagship species, all the other creatures get conserved too.Our not-so-popular projects are those in the rainforests because people associate them with snakes, spiders and mosquitoes.

One of the most popular is in Oman, where people know it's a climate they can cope in. It's images that drive people; and it's the same with flagship species.

What risks are involved in using untrained people in conservation work?

Our tagline is Experience Conservation in Action. We want to be as inclusive as possible, get people out of their armchairs to help scientists in the field.

The beauty of biology is that it's like stamp collecting. For example in Oman, the area is huge, with a lot of wadis to cover. No satellite technology can tell you how many leopards are in there – you need eyes on the ground.

Within a day or two, we teach everyone what a leopard scratch or spoor looks like. Then it's a matter of splitting the group to cover different areas. They all have digital cameras to take pictures, and get a second opinion from the scientists in the camp.

In Namibia, we have an expedition on cheetahs. Part of the project is catching the cheetahs in the 12 box traps we have set up around 200,000 acres. If it were just up to the scientists to check on the cheetahs, it would take them all day driving around to see the box traps.

And if they didn't check them by noon, an animal like the aardvark, if it were trapped by mistake, would die because it can't stand the sun. So our team takes over this task and surveys the area in their Land Rovers to check on progress.

If you design the project properly, then lay people can do a lot of useful work. The amount of data we get is amazing, and the scientists are very grateful.

With so much travelling, you must have a very large carbon footprint?

I'm home about 80 days a year. Yes, I do have a very big carbon footprint. But there are two points to be noted. One, we calculate all our carbon footprints before the expedition starts and offset it by working with organisations like Climate Care.

We encourage all our team members to calculate the carbon

deficit they incur through travelling to the expedition assembly point and back home again on a voluntary basis.

For a relatively small sum, Climate Care can then help remove the same amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as is produced by flying or other forms of transport to the assembly point.

Second, I look holistically at my overall impact on the planet. I can justify travelling these distances with the conservation work I do in all these countries.