Anonymity, middlemen, catalogues, predictability, exploitation and gravity – just a few of the things that Thomas Lundgren set out to 'save' the world of interiors from some 10 years ago.

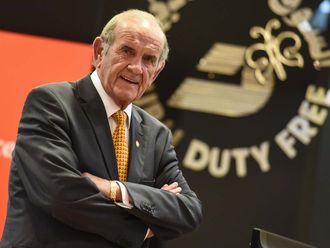

The 45-year-old Swede is the chief emotional officer/Dr Funkenstein/ anti-gravity manager/founder-to-you-and-me of home fashion brand THE One.

Obsessive and given to extremes in all aspects of life, Lundgren boasts six designations where one would do – in fact his several business cards are his way of cocking a snook at corporate hierarchies and conventions.

Like its founder, THE One delights in its over-the-top theatrical idiom: stores are theatres, customers are fans and staff is cast. Store interiors sport achingly hip touches such as mocha-brown crocodile skin wall panelling and red lights in the toilets.

Touching, yet funny are the two walls full of framed rejection letters, all gathered when Lundgren was looking for a project financier – they are the educational degrees he earned in the university of life.

What's less well known is that Lundgren spent 10 years of his life at IKEA, a company his branchild now competes with. Lundgren arrived in Saudi Arabia from his native Sweden in 1984, as a decorator for IKEA.

After a year, he moved to Kuwait as decoration manager and stayed on for nine years.

Ingvar Kamprad was his inspiration. Lundgren lived and breathed the dream of the IKEA founder who travels economy, eats at cheap restaurants and has made flat-packed furniture a cult classic.

However ...

The oft-repeated story is that he had a dream in which a visitor came to him with a message: "To save the world … by establishing the funkiest home fashion brand on the planet."

He turned entrepreneur, a rollercoaster journey that has been riddled with coincidences and catastrophes – including a fire which completely gutted his first store.

Despite a rocky start in 1996, THE One is doing well. By the beginning of 2005, it had nine 'theatres' across the Middle East – in Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE.

Like his erstwhile idol Kamprad, Lundgren's goal has also been world domination. In June 2005, he opened a store in Stockholm, a 10th in Dubai's Mall of the Emirates later in November and seven months later another larger one in Stockholm's Frihamnen port. In the pipeline are openings in Qatar, Istanbul, Beirut and Malta.

"Our new goal is that we are going to have 50 stores by 2010 and 201 stores by 2020. How we do this without becoming a big and boring corporate is the challenge," he says cheerfully.

So it comes as a shock when despite all his successes, Lundgren says he is depressed. "When you are like me – dedicated, crazy and extreme – depression is a part of that. I find it hard to pat myself on the back and say 'That's good Thomas'. That dissatisfaction is actually what drives me. But it's also kind of sad that you cannot enjoy your success. Everything in life has a price. Sometimes I wonder, had I been a mailman would I have been a happier person?"

I

I am obsessive compulsive about everything. I do things in extremes. That's why my wife, Ewa, is the stable one. She brings me down when I am in the sky, and cheers me up when I am low. I cannot do anything in moderation.

I am a modern dad of three teenage daughters, who can get anything out of me. I wouldn't know how to [be a] father to boys. In a word, I am compassionate. A friend. There is no difference in the way I am at home or at work. Both employees and children need to know the boundaries. The rewards can be love, affection or different things. It's the same thing with employees.

I do not deny myself food. There are many things I deny myself [but] I love food, that's why I am overweight. I should eat less.

I began to reassess myself after my open-heart surgery four years ago. It made me more philosophical, which is good. It made me step out of the company for a little while, which was overdue. When you are in the middle of things you can't see many things. I got more 'me time' so I could come up with great ideas.

I cannot change the world sitting behind a desk.

I like to rebel … against what is conventional. I don't like someone telling me what to do. [I] rebel against what's wrong in the world.

Me

Me and growing up in Sweden:

I was born in 1961 in Ostersund. When I was 5, we moved to Stockholm.

Let me elaborate on this. One day in advertising school, we had one of those do-art-in-any-form-and-explain-life sessions. A professor put thumb tacks all around the room.

He then took a thread and tied it to one of them and said, 'I was born here'. Then he drew the ribbon to [another tack], and said 'then I moved here …' Thus saying, he created a pattern by tying the thread to various [tacks]. That is life.

Moving to Stockholm was a turning point. If I had stayed in the north of Sweden, I would have probably still had that same, smaller world view.

[In Stockholm], we stayed in a house my father rented. He died of a heart attack that summer and my mother and I were left in a home we didn't own. I wasn't allowed to attend his funeral, because it was decided I was too young. My mother didn't work at the time. Although she helped people find hotel rooms and apartments [that's how my parents met].

We got a small sum of money every month [from the government] because my mother was widowed after five years of marriage. We lived on that. The way I was brought up is a big part of how our company is run today. We had nothing. We couldn't throw anything away and ate everything. [It may have been during that time that] I developed an aversion to leftovers that lasts until today.

At the time, I didn't know of the existence of any other sibling, except for my half-sister [who is like my sister]. But my father had been married five times before he met my mother. After his death, I learnt that I have some siblings.

My upbringing has mostly been all about my mother and I surviving [whatever the odds]. But my mother, like most mothers, had a knack for overcoming hurdles. I always got everything that [I needed].

I liked to draw. My mother always supplied me with lots of pens and paper. For some time in my life, I was quite lonely because I didn't know many people. So I would draw all day.

The next thing that changed my life was ice hockey. I played every sport, including soccer and ice hockey. And I became pretty good at it. You play sports to be popular, especially with girls. Our Hammarby team went on to the highest division.

When I was 10, my mother decided to start working. But I cried my eyes out [because I feared I would miss her], so she dropped the idea. When I was 12, I got a chance to go to Canada to play hockey for two weeks.

Quite a few kids, even though they had both parents who were working, were unable to make it because the programme was very expensive. But my mother was keen to send me and, what's more, was keen to join me on the trip. She said, 'I am going to fix this so I can come with you'.

We did everything we could. We collected cans and old newspapers and sold them ... but we couldn't save enough money for her to join me on the trip.

My tour to Canada changed me a lot. I stayed for over two weeks with Canadian families. My dream was to be the national goalkeeper.

Me and my higher education:

[During my early] life, I was praised for my talents in drawing. I heard of this advertising school, Anders Beckman, and decided to get admission into it.

There were close to 400 aspirants for seats in the school. Eighteen of us finally made it; I was the youngest in the class. On the first day, the master looked at us and said, ‘Do not think you are special. The reason you are here today and the other 400 are not is simple. When you were a child and your parents asked you to draw a horse, you drew something that was hardly like a horse.

But they still appreciated it and said it was beautiful. You continued drawing horses and by the time you were 10, got pretty good at it. But as for the other kids, when they drew a horse, their parents would tell them, 'Listen. Let me show you what a horse looks like' and they would draw it. Somewhere down the line, the children gave up.'

I think that's a very important thing to learn in life. You can't force children, just encourage them.

I finished that programme in 1982 but I started to have a really bad attitude. I had a new ice hockey trainer whom I didn't respect. In the summer of 1983, I was fired from the team. I had wanted to leave ice hockey for some time. I may have been just tired of it, I don't know. I wanted to leave, but did not have the guts to resign, so I acted up.

It was during this time that I met Ewa.

I had just finished school and was working as a photographer while she was working in a photo lab. Twice I invited her out to lunch but for some reason or the other we could not make it.

That summer I saw an ad in a newspaper. IKEA was recruiting decorators for [their store in] Saudi Arabia. I started to think about running away from my whole life. After being fired from the ice hockey team, I wanted to leave the country.

I had no qualifications for the job ... [but I applied and was selected].

I invited Ewa out to lunch for the third time and this time we did manage to meet ... and I told her the lunch was to celebrate my new job in Saudi Arabia.

Me and moving to the Middle East:

In December we got engaged. On January 5, 1984, I moved to Saudi Arabia. The first display I did was of IKEA's cooking pots. I had a good time in Jeddah. I went out fishing and exploring parts of the kingdom with my Saudi friends.

Ewa and I wrote romantic letters to each other. (Phone calls were expensive at the time.) Five months later, we met in London for a holiday and it was like restarting the romance all over again. I went back to Saudi Arabia and she returned to Sweden. But that wasn't working out for me. I wanted to resign. IKEA then gave me an option of working in other countries. In Kuwait I was offered the post of decoration manager. I negotiated with the company so that Ewa could join me after being trained as a decorator and I succeeded. She joined me in Kuwait by the end of 1984.

IKEA is a fantastic school. I dreamed of the place. I could discuss it non-stop. I was dreaming the dream that the founder was talking about. I could explain the smallest change in the catalogue. We were supposed to stay [on in Kuwait] only one year. But we ended up staying from 1984 to 1990. Our maid, Claura, came to work with us in 1986, and she is still with us. She was like a mother to us.

Ewa and I got married on October 16, 1986.

Me and the First Gulf War:

Our daughter, Izabel, was born in 1989 and Ewa [had taken the baby and gone to Sweden to spend some time there]. In August 1990, I went to Sweden to fetch Ewa and Izabel. I had planned to go for just five days but on the second day there, Kuwait was invaded.

We hadn't bothered to send money home and thus everything we owned was in Kuwait. We lost it all. All that I had was a pair of shoes and a few clothes. We were staying in Ewa's parents' summer house. I went to the Swedish welfare office to borrow money but was rejected because I was not really a refugee.

We borrowed some money from Ewa's parents [and survived on it].

Meanwhile, a friend of mine knew someone who had a chain of record stores that had been bought over by Sony. They were looking for someone to manage it ... and I started working in the music business.

After the Kuwait problem was over, I couldn't make up my mind whether to stay in Stockholm or return to Kuwait. But Ewa made up my mind for me ... and we decided to return to Kuwait though Sony wanted me to stay on in Stockholm.

Me and returning to the Middle East:

After our first daughter was born, our life changed. I was Izabel's daddy. That was a big responsibility.

Also, the urge to move on was getting stronger so Ewa and I sat down to figure out what to do next …

Me and turning entrepreneur:

I came up with an extremely stupid idea – to start a consultancy. We set up Scandinavian Commercial Establishment [in 1993]. I was looking at Bahrain and Dubai as places to establish the company but settled on the latter. I don't know why.

One day I got a call from the Danish Furniture Manufacturers Union. They were doing a marketing study on Middle Eastern [furniture trends] and wanted me to make a presentation. We had no customers and it was a free lunch, so I went. I put forth some ideas which the chairman liked. He told me, 'If you can put up a business proposal, and you get some of our members to approve it and invest some amount in it to show their commitment, our lawyers will buy the business idea and in the second phase you can receive funding from us.'

I got around Dh300,000 from them. It was the only money I ever earned as a consultant. And off I went. I put on my fake glasses and went in search of financiers for my idea. The project was called The Home Scandinavian Experience.

Me and my search for partners:

For all of 1994 nothing happened. In the spring of 1995, there was no money left. Again, I asked Ewa whether we should shift [our business focus] or continue till the bitter end, and she said, 'Continue.'

My idea was to have a partner from Saudi Arabia, one from Kuwait and one from the UAE, each investing $1 (about Dh3.68) million. I met Rashid Al Mazroui, my partner in Abu Dhabi. He listened to me without patronising me, he was rather nice to me. An [acquaintance] suggested I call up Shakir Abal Sadeq, a businessman I had befriended in Kuwait. I called him and asked, 'Shakir, do you have a million dollars?'. I fully expected a refusal. But he had just closed one of the biggest deals in his life and had the money. He retired and became a partner in the project.

So that's how THE One started.

If you look at the first store we opened in Abu Dhabi, it's clear that I worked in IKEA. I had lived and breathed the concept for so long, it was difficult to get it out of my system. There were visions in my head which I didn't quite manage to verbalise or explain to people. It was not [really] my dream. What we have today is my dream.

We suffered a fire which could have destroyed us. It took us seven years to stabilise. The last three years have been better and better.

The journey of THE One has been hard work, with a lot of coincidences. Fate is something that you use to float through life.

Myself

Has your lack of formal degrees ever hampered you?

I have a lot of views about schooling. I think our current schooling system is all wrong, because it doesn't work. It was set up for the beginning of the 20th century. Have you ever seen how sausages are made? How the meat is forced into the skin? The school system is like making sausages. You cram it in for a test, and you take it out the other end. It was good for the industrial society, but that time is over. If you have some brain cells, it's easy to play the system. I was pretty good at doing that.

I am dyslexic. But my dyslexia wasn't diagnosed. My teachers made me read more instead, because I couldn't spell.

Two of my children have dyslexia. If you are different, with problems that other children don't have, you either fight it or you fall off by the wayside. A lot of children just give up because of the negativity.

I am not sure if it's good to be diagnosed. Because when you are diagnosed, you tell yourself this is the reason I cannot accomplish this or that. I didn't know about my dyslexia and found out three summers ago when I took my kids for tests. Everything they couldn't do on the test, I couldn't either.

Out of all your designations, which one is a personal favourite?

I love being chief emotional officer, above everything else. Emotions are at the core of what we do.

What is the downside of becoming such a hot success?

We lost a little bit of the focus on the goal. Survival is a very strong goal. I succeeded because I was too scared to fail. Failure is a strong motivator ... You perform best when you have your back against a wall. When you become successful, you lose that strong focus on a goal.

We are now in a perfect little sandbox, a comfort zone. I don't like it. We could perform much better. I am not happy.

When I was dreaming this dream, there was a goal. Under pressure we were performing much better. When we were just 12, we were 12 stars. Each one of us over performing. Now we are 80, but we are not 80 stars.