To self-discovery. That is Paulo Coelho's eternal quest. And the journey brought this world-renowned literary genius to the UAE. Shalaka Paradkar reads through the many chapters of his mind.

At the height of Bill Clinton's Monicagate scandal, he turned to the slim story of a Moorish shepherd boy for wisdom. Clinton was in august, if eclectic, company.

Other fans of the parable have been Madonna, Julia Roberts and Nobel Prize winner Kenzaburo Oe.

The Alchemist has been regarded as a publishing phenomenon of the 20th century. When it was first released, its slow initial sales prompted his first publishers to drop the book. It went on to sell 32 million copies in 18 languages.

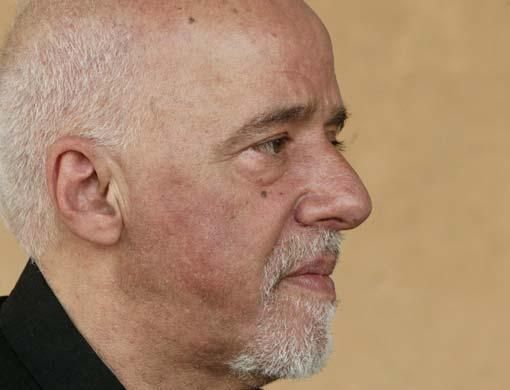

"If you don't dare, you don't arrive anywhere," says Paulo Coelho, the author of The Alchemist, who was recently in Dubai. "People here are daring to take new steps, to go beyond the limits. Every time I'm here, I feel recharged by people who have dreams and fulfil them."

Coelho's own journey to this day in Dubai, when he launched his latest novel, The Witch of Portobello, was a lesson in courage and facing one's own destiny.

People pack the venues in Dubai where Coelho, dressed in trademark black, signs copies of the book and speaks to them. He is immensely likeable, speaking straight to people's hearts and minds. And he no doubt has won a whole new set of admirers, releasing his latest book in English and Arabic.

This move, he says, was designed to counter "this idea that there is a clash of civilisations, which is not true at all. We speak a common language, this common language is love, but at the same time we have to advertise to enhance the fact we can have a dialogue."

The Alchemist was partly autobiographical - the story of a young shepherd boy who travels many thousands of miles, only to discover that the answers were always within him. Author Paulo Coelho's own life story has actually been far more complex and dramatic.

Coelho, 60, grew up in an upper middle-class family in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He always wanted to be a writer, but it was a dream his parents opposed, thinking it would only get their son a prison term under Brazil's military junta. Coelho refused to give up his art.

His parents - not knowing how to handle their son's acts of rebellion - decided that shock treatment was the only way to bring him to his senses.

Coelho spent three stints in psychiatric hospitals, where he was administered Electro Chemical Therapy (ECT). (He used his knowledge of the inner workings of mental institutions and their patients 30 years later in the novel Veronika Decides to Die.)

In his twenties, Coelho became a hippie, travelling the world, learning about secret societies and oriental cultures, while immersing himself deep into a debauched rock 'n' roll lifestyle.

In 1974 he was arrested three times, for crimes including stolen ID and speaking out against the Brazilian government. The torture he endured in prison marked one of the darkest periods of his life.

In 1979, he got a high-profile job as artistic director of CBS Brazil, but was sacked and became jobless. His first book came out in 1982, but flopped. It was followed by a more embarrassing contribution to the Practical Manual of Vampirism in 1985, documenting his dabbling in the occult arts.

Coelho tasted spectacular success as a lyricist though. Teaming up with record producer Raul Seixas, he wrote many hit songs such as Gita and Al Capone for some of Brazil's biggest stars.

Yet despite the money and trappings of success, he says he wasn't happy. It all changed after he undertook a life-changing pilgrimage, on which he finally decided to fulfil his destiny.

Today, Coelho lives in a stone cottage near the pilgrimage town of Lourdes in southern France - a place he believes is his spiritual and creative muse. Though he left the world of rock 'n' roll for literary pursuits, he is given a reception befitting a rock star wherever he appears for book signings.

As he says, "Of all the things I have experienced in my life, I could have chosen to be a victim, but I always chose to be an adventurer."

I

I am still a child within myself. When I try to write, it is to speak to this child within me and within everybody. I try to go back to the things I heard or read about in my childhood. But when I was a child, I was different from the others. I was a misfit and a loner.

I was a bad student at school; it was one of Brazil's most rigid Jesuit schools which inculcated a lot of discipline in me. That helps me a lot in my life today as a writer, because without discipline, you go nowhere.

In school, I always read a lot of books that were not a part of the curriculum. My grades were very poor, but the teachers accepted that I was different.

Though personally, I never felt like an outsider. All children are different. The problem is that society tries to push them all into the same mould, telling them, "You have to be like everybody else".

That's why most of my books deal with the importance of accepting our differences and fighting for them.

I am a Brazilian who writes in Portuguese, there are a lot of barriers before you become a world writer, a translated author and Portuguese does not have a literary tradition. But, thank God, I did not quit.

I had a dream. For many, many years I tried to deny this dream, I tried to say that it wasn't possible. Then, there was a moment in my life when I was 38. I had nearly everything - love, money, a house - but I was not happy.

Then came the turning point. I said, ‘Why am I unhappy? I am unhappy because I am not doing what I want to do and that was to write.'

I was a lyricist before I became a writer, and my most famous song, Gita, was based on a mythological epic.

Me

Me and my childhood:

I grew up in Rio de Janeiro - my father was an engineer and my mother a housewife. I have one younger sister. Growing up, I had the same joys and sorrows as any other child but, yes, I wanted to be an artist or writer from the day I won a prize in school for my poetry.

As a teenager, I had a very troubled time. My mother and father were bitterly opposed to my dream. They thought with all the great schools I had been educated in, with all the contacts my father had, it was foolish for me to want to be an artist. In our family, we have no tradition of being artists.

When I was 17, my parents decided that shock treatment was the only cure for me. My parents locked me up three times in a lunatic asylum.

I was not crazy but I was rather just a 17-year-old who wanted to become a writer. I promised to myself that one day I would write about this experience, so young people will understand that we have to fight for our own dreams from a very early stage of our lives.

In the end I think these clashes were good for me and my family - we ended up understanding each other. They made me grow and understand I had something to fight for. It made my parents see the world in a different way.

No, I still haven't got my parents round to my way of thinking. But this is what was good about the experience - they now accept that people can think differently.

I had a lot of pressure from society to follow a certain path that was not my dream, but was more comfortable. I had to fight for my space. That was probably most challenging for me.

Though I wouldn't say it was painful. When I look back, I think it was necessary. Unfortunately, I gave my parents a hard time. My father is still alive today, he in his nineties. We have had a fantastic relationship since my early twenties, when they began to accept me as a black sheep, but also someone to be loved.

Family is very important to me. There are some values to be treasured. My father is quite proud of me today, but he still doesn't fully understand the range of what I do - neither do I, by the way. My family gave me some important lessons in life, like honesty and discipline.

Even though we were quite well off, they were tough about money. You are a product of your family. When I had to fight for more abstract values like my dreams, my family was good for me then as well - because they provoked me.

Myself

You described writing as a spiritual journey. How do you reconcile yourself to the commercial aspects of getting a book to the market?

This is not a publicity tour. Whether I am here or not, it makes no difference to the sales of my books. The life of a writer is a lonely one and the only way to meet people is by travelling. What I treasure most on these trips is the possibility of interacting with people.

Every journey is a pilgrimage. Even going from home to your workplace. You can think it's another ordinary, boring commute, or look at it like a pilgrimage, where you meet new people every day and see different things.

A classic pilgrimage makes you feel much more vulnerable. This is good - you realise you are dependant on other people, you understand you have to travel light. It is symbolic of how we go through life, weighed down by too many things that we accumulate.

On a pilgrimage you understand you cannot take everything with you. You have to respect your own way. And finally you have a goal in mind, but you have to also enjoy the journey.

So I think the symbol of a pilgrimage is to get away from your comfort, and allow yourself to have different inputs that can change you.

Every journey is a memorable journey. But the most special one for me - the turning point - was my pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain, 21 years ago. It was on that journey that I decided to face my destiny and write. I was 40 years old.

I was writing lyrics and articles, but my dream was to write books. At the end of this pilgrimage, I decided that I could not live with this schizophrenic behaviour anymore.

I decided to stop doing things that made me half happy and go for things that would fulfil me, even at the cost of getting a few scars and being hurt in the process.

Did you ever expect or prepare for success?

Of course not. Even now I don't expect it. When I write, it is for myself. It gives me hope. My readers and I share a lot of things; when people can relate to the same story that I tell, that is fantastic.

But there is no formula for success. If you try to find formulae, you get lost. I am very free in the way I write, though I like to travel light - back to the metaphor of a pilgrimage, in which I like to reach the essence without speculating or describing too much.

I leave the floor open to my reader to co-write the book. If I have to describe Dubai and the life of a calligrapher in the desert, I won't do it in detail - my reader is the co-author.

The magical tradition of Latin writers is inspiring, as is the Arab one. When I read the so-called fantastic realists, I was too old to be influenced by it. Having said that, being Brazilian was more helpful. Brazil is a melting pot of so many cultures with influences from all over the world.

What has affected you most deeply of late?

One of the greatest challenges confronting humanity today is this clash of civilisations. We are living in a very complicated world when we are using prototypes to define entire cultures - be they Arab or South American.

We are losing ground, because archetypes are easier to deal with ... we should fight against that. I think the biggest challenge now is to get rid of these prototypes and go back to who you are as a human being.

For writers, and artists in general, it is a very important role they have to play. The only bridge left is art, because - thank God - we can still understand each other's art .