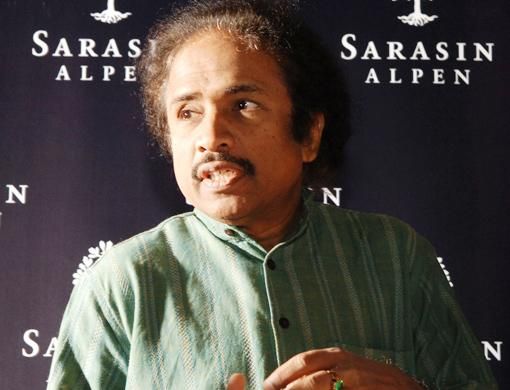

Humility, gentleness and compassion - these qualities are not exactly common among music stars, but then Dr L. Subramaniam is no conventional musician. A pioneer of global fusion, he tells Shalaka Paradkar that without the support of his parents, he would never have reached such dizzying heights. And that's why he wants to do the same for his kids

The man who opens the door on a quiet Friday afternoon is simplicity personified. The most striking aspect of his cotton-kurta clad persona is a polite, unobtrusive humility.

He speaks in a low, measured cadence, while his wife fusses lovingly over him - plying him (and his visitors) with tea and snacks. As he talks about his life, she continues to quietly iron his clothes in the background.

After some discussion, she chooses a silk tunic that he will wear in the evening and chips in with some gentle humour from time to time.

They could be any other middle-aged Indian couple, discussing their three children and upcoming holiday plans.

But for the fact that Dr L. Subramaniam has been likened to Bach, crowned the Paganini of Indian classical music, jammed with the likes of George Harrison and composed music for Mira Nair's Salaam Bombay and Mississippi Masala - in which he mixed jazz and R&B with the sonorous vocals of Bollywood great Mukesh.

And his wife Kavita Krishnamurti Subramaniam has recorded over 15,000 songs for Indian films and is one of the most popular artistes of her generation.

To see them in this light, the picture of quiet domesticity, is as heart warming and soul stirring as one of Subramaniam's own compositions.

A medical doctor who knew he was destined to be a musician, Subramaniam is a pioneer of the global fusion music genre, straddling European classical music, American jazz, rock and South Indian music.

His musical family ensured that he received solid and scholarly training in South Indian classical music, known as Carnatic. He moved to Los Angeles in the 1970s to earn a postgraduate degree in Western music at the California Institute of the Arts, where he also taught South Indian music.

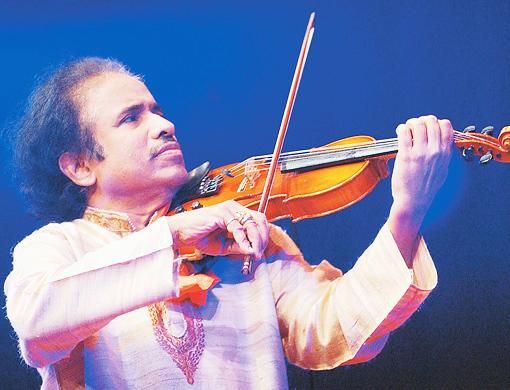

The genius tag may even be inadequate for his talent. There is almost no other musician today who has performed and recorded Carnatic and Western classical, orchestral and non-orchestral and also composed for and conducted major orchestras.

Subramaniam fuses classical music, electric and acoustic jazz with South Indian music, while also being a prolific composer who has collaborated with greats like Stu Goldberg, Larry Coryell, George Duke, and Stephane Grappelli and several Indian artistes.

A child prodigy, Subramaniam was given the title Violin Chakravarthy (emperor of the violin) when he was 11. He has produced, performed, collaborated, conducted and released more than 150 recordings. He has established himself as a force that is strongly Indian, but universal in nature and approach.

Subramaniam's first wife, Viji, passed away in 1995 after a protracted illness. Music has helped him deal with his personal griefs, and brought him much joy as well.

He composed Fantasy on Vedic Chants for maestro Zubin Mehta in remembrance of his mother, then Shantipriya (Beyond...) for his father. He married Krishnamurti in 1999, after falling in love with her voice and the way she was embraced by his children.

As he narrates his story, it's eminently obvious that he regards music as his way of paying homage. As he puts it, his mission is to "speak my truth gently, not to hurt anyone, and to try to be a good human being."

I

I grew up surrounded by music all the time - either my father would be teaching or there would be students coming to meet him. When we were not sitting and learning from him, there would be others.

I have never thought of music as a job. It has been a passion, a commitment. There is a lot of spirituality involved in music ... it has to be sincere and come from the heart.

If you do a composition, it is not just for one concert but with the fervent hope that it will be played for many times to come. Most of my orchestral compositions have been played even after I finish premiering them.

My music involves me so completely that little else matters. You could easily say my music is my life.

I have done over 150 orchestral performances of my own compositions. That is beyond anyone's reasonable expectations for a lifetime. But I hope this will continue beyond my lifetime.

I hope my children will be as passionate about music (as I am) and have humanistic values for art and people. They are dedicated to their music, but I hope they go on to discover, innovate and bring more people to music.

Music is more than playing seven notes, you have to bring life to them - it cannot be done mechanically.

I love water and going on boat rides. But we rarely get time to unwind. I don't enjoy plane travel, though my profession necessitates that we spend a lot of time in planes. I like taking pictures and enjoy the unhurried pace of travel by rail or boat.

ME

Me and my father:

My love for music was inherited from my father and guru, Professor V. Lakshminarayana. My father and mother, L. Seethalakshmi, were the driving forces behind me choosing a life in music. My mother started learning vocal music and the harmonium when she was 6.

I have three sisters and two brothers. We stayed in Sri Lanka from 1953 until 1958 and then shifted back to India. My mother was a fabulous singer and a great inspiration.

My father was a very strict person, yet he was also very loving. Whatever he said was acceptable to us because we admired him so. My mother was a very quiet, kind and loving person; she would even hesitate to scold us.

My father was very strict about music practice. He would not tolerate any excuses - such as schoolwork or exams - if we missed practice.

Then he would ask, "Did you sleep? Did you have breakfast? Did you bathe?" If you had time for all these things, you had time to practise music. There was no arguing with him.

He was also very methodical as a teacher. He was very keen that we should learn the scientific theory (behind music) and the reasons why music was played the way it was. I believe this approach honed our skills.

He constantly wrote music right until his demise. It was his passion. The violin is (famous) today because of what he has done. It was just an accompanying instrument in classical Carnatic music until he made it his priority to make it recognised as a solo instrument.

I was very fond of science and when I decided to take up medicine, my parents encouraged me. I remember one incident from my second year of medical school.

A German violinist, my father's acquaintance, wanted me to come to Germany and stay for a few years because he thought I showed promise. I was thrilled at the prospect ... but my mother flatly said I wasn't going anywhere until I finished my medical studies.

She said I was free to do anything and go anywhere after I became a doctor. That was shocking for me, I was quite upset. It was also a big shock for my father. But my mother was very particular about education, something I only appreciated later in life.

Had I gone to Germany, I would have been just a high school graduate. So I resolved to complete my medical studies and become a doctor, but work as a musician. That incident was a turning point for me - it made me realise how eager and passionate I was to be a musician.

I started playing a lot of concerts in Chennai while studying in medical school.

I was fortunate to play alongside such maestros as Chembai Vaidyanathan Bhagavathar, one of the greatest singers of that generation, T.R. Mahalingam, probably one of the greatest flautists India has ever produced, and Palakkad Mani Iyer, the mridangam (Carnatic drum) player.

There were almost two generations between these artistes and me. But Chembai Vaidyanathan took me under his wing and I accompanied him to concerts everywhere.

Palakkad Mani Iyer was very selective about the artistes he would play with - no amount of money could persuade him to play with anybody not of his choosing. It was thanks to the encouragement of these artistes that I thought of becoming a soloist.

Me and going to the US:

After finishing my medical studies, I had a choice to move to Los Angeles or New York (to study music). I decided on California because of its lovely weather. I did my master's degree in Western classical music in nine months flat.

It was ironical, because in Chennai where I had performed at so many concerts, the university red tape would not let me to do even a BA in music.

But in the US I could wrap up the course and get a postgraduate degree in nine months.

But I was so homesick. I missed everything about home, especially my parents. When I was studying medicine in Chennai, sometimes I would come home really late at night and my mother would still be up, waiting for me.

She would heat my dinner and serve it. Those little things, that affection and caring, were what I missed the most when I woke up in the morning and made my way to a diner to have coffee.

At home in Chennai, we would go to different functions in temples and perform music, which I missed terribly in California. I also missed the company of the greats of Carnatic music whom I had performed with in Chennai.

My father was my idol for many years and I missed hearing him play.

I worked very hard ... partly because I was so homesick. My professors were very generous in their praise, especially those who taught me composition. I would practise music until I was dead tired.

Music helped me forget the absence of family and loved ones. Food wise, I was not a fussy eater. I got by eating bread and butter with jam or pickles. A little later, I discovered canned soup. In the late 1970s being a vegetarian in the US meant you could only eat salads.

Ultimately, my father advised me to stay in the US and continue working there. He was dead against house concerts - where Indian artistes toured the US, holding concerts in the homes of wealthy Indian professionals who had emigrated to the US.

Or in a best-case scenario, they would hold a concert in a high school auditorium, never in a professional theatre. My father wanted me to bring Carnatic music into the mainstream.

Once I completed my course, I had the option of returning to India for a year and coming back to collect my degree or staying on campus as part-time (tutor of South Indian music. I chose the latter).

Me and the start of my career:

In those nine months in the US, a lot of things happened. I was invited to go on tour with George Harrison, who was promoting Ravi Shankar. This helped me establish myself as a soloist.

I also started playing jugalbandi with Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, one of the greatest musicians India has produced. We played in some great venues and cut a couple of albums from these concerts. From those performances, I got offers to play with the likes of Yehudi Menuhin and Stephane Grappelli.

When I did my masters in Western (classical) music, I also specialised in composition, learning about harmony, history and different genres. I worked very hard, because much of this was new to me.

The first orchestra I wrote was a double concerto for the American Orchestra conducted by maestro Jack Elliott. I had some misgiving though at the time about writing for orchestras.

I thought it was a dead field, as most of the composers who write orchestral pieces rarely get to hear them being performed in their lifetime.

I was given a couple of dates at the Music Centre, where the Los Angeles Philharmonic performed and six months to write my first orchestral piece, which would be premiered at a concert.

I decided to write a double concerto with the Indian violin and a Western instrument, so it would create a global fusion genre. I thought of writing it for Hubert Laws, one of the finest flute players with a strong classical background but also a fantastic jazz musician who improvised so well.

When maestro Zubin Mehta heard this performed in 1983, he asked me to write an orchestral piece for the New York Philharmonic.

My collaboration with jazz violinist Stephane Grapelli almost did not happen. Grapelli wanted to attend my concert in Paris, but did not have a ticket. He asked for permission to stand at the side of the stage and listen.

But the French organisers would have none of it. Finally, the director of the organising forum gave up his seat for Stephane. That was the beginning of our friendship which resulted in the famous album Conversations, which was released in 1984.

Myself

Kavita and you are from opposite ends of the musical spectrum. She is schooled in the North Indian/ Hindusthani tradition and has been a Bollywood singer, while you have such a strong base in Western classical and Carnatic. How do you make it a melodious union as co-artistes?

Though I had done some recordings with voices, until I met Kavita my specialisation was fusion with instrumental music. Her versatile voice inspired me to write more for vocals.

Most of our concerts where we have performed together have been very successful. As Kavita says, the home unit in a musician's life has to be very strong, so he can focus on the music.

Kavita made me think a lot in terms of Hindi music. She, in turn, imbibed a lot from South Indian classical music and international music.

To commemorate 100 years of the Nobel Peace Prize, an album that brought together the best from music and excerpts from speeches of Nobel laureates was released. We were chosen to represent the Asian continent.

We have also performed together at the re-opening of Bibliotheca Alexandria in Egypt which was attended by President and Mrs Mubarak of Egypt, President and Mrs Chirac of France, Queen Noor of Jordan, the Queen of Spain and Queen Sophie of Belgium among other heads of states.

My album Global Fusion was a critically acclaimed milestone and features artists from five continents including Kavita and my talented and versatile daughter, Seetaa.

You were a musical prodigy and now are a parent of three talented musicians. What are the challenges and joys of parenting a prodigy?

One thing is to get them to practise. My father disciplined us to practise music. I am not like my father, in that I cannot be so strict. Also as a travelling musician, I am rarely at home.

I do not want to be a tough parent during the three days I am at home. I give them assignments and hope and pray that they will work hard at their music.

My daughter Seetaa is into Western classical and fusion music. She is also studying law. Like my mother had insisted with me, I insisted on her completing her law degree before turning into a professional artiste. She has accompanied me on several concerts.

My second son, Raju or Narayana, writes poetry and loves ghazals and film music. He has just joined medical school, but is clear that he wants to complete medical studies before turning to music.

My youngest son, Laxminarayanan, better known as Ambi, plays the violin. He is passionate about becoming a violinist and has played with me in Dubai.

I do not spend enough time with them on account of my concert schedules. I am hardly at home. My children have accompanied me on tours (in the past) but with their studies now, it has become very difficult.

As a father, one worries a lot about the children. Often when a child is ill, your first thought is to cancel the tour and head home to be with (him).

But as a musician, you also have responsibilities and commitments to the audience and organisers. Sometimes it's difficult to manage it all. But thanks to Kavita, I manage.