The world doesn’t need a McLaren P1, a 903bhp and 900Nm Le Mans prototype with registration plates. But the world wants it, badly. McLaren simply felt like demonstrating the ultimate in cutting-edge automotive technology, and the P1 is that showcase. Two highly efficient powerplants and a lightweight carbon chassis weighing no more than 85kg ensure that the P1 provides blistering performance from the 727bhp 3.8-litre twin-turbo V8 and 176bhp electric motor.

There are hushed whispers of sub-seven-minute Nürburgring Nordschleife laps as we surround the P1 at one of Dubai’s five-star hotels, as wheels gets busy with an exclusive photoshoot session at the crack of dawn. There’s a VIP session in a few hours, but they let us in anyway. Up on the pedestal, the P1’s covers are taken away and the orange collection of curves and shapes — it’s like an abstract sculpture — come across as much more compact than I thought.

I am told it’s the first thing everybody says about the car. The rest is just guesswork — the interior, the technology, the brakes are dummies, the tyres are cut slicks with McLaren logos, I can only imagine the performance of a car that’s reportedly six seconds faster than an MP4 GT3 racer around a track. “This is a car for connoisseurs at the ultimate level,” director of McLaren Automotive Frank Stephenson tells wheels.

McLaren, being quite handy in the Formula 1 business as well as selling cars, allowed the automotive side to inherit a lot of know-how from its Formula 1-development side, which is always at the cutting edge. “You can’t relax in Formula 1 and expect to be at the very top, so because we’re such a small and tight company, that Formula 1 expertise is allowed to come into the automotive side.

The interesting thing is that even the things that are not permitted in Formula 1, because of legislation and regulations, are technologies that are allowed on the road cars. So a lot of our technology that is not allowed because it gives you too much of an advantage in Formula 1, can be applied [here with the P1].” But the birth of the McLaren P1 started before Stephenson and the engineering team asked the F1 guys if they could borrow some bits.

“This car’s design and engineering, as opposed to the way that a lot of cars in the industry are designed, was brought together at a very early stage in the process, which means that from the design kick-off any proposals that we make have already been run through with engineers in detail to make sure that whatever we do is not impossible to execute.

This is forward-thinking obviously, it pushes the limits but all within the realm of what’s possible with a real nod towards making the car performance-orientated. It’s our philosophy that if the car works well, it will also look good. It has to really perform and then we add that emotional touch to it to make it visually attractive or appealing. So you can’t just say that it was designed in the styling studio or was engineered in the engineering studio, it’s really a combination of the two departments working closely together to achieve something uniquely McLaren.”

Stephenson and McLaren also looked to the Nineties’ F1 roadcar for inspiration, since that legendary Gordon Murray-designed model is the P1’s spiritual predecessor. “We respect the fact that people see this as the successor to the McLaren F1 and yet it makes a huge leap in every respect to the F1 and I think one of the great things along with that is that it looks like a McLaren — if you saw it even though it is our first hypercar in the new range of McLaren Automotive, the P1 does look like it could only be a McLaren.

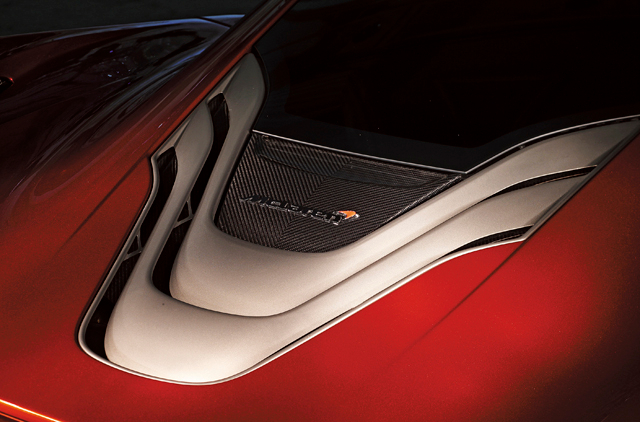

“What we tried to achieve in the very beginning was a very tight car where excess was the enemy, not only in weight, but also in terms of surface. So the smaller you can make a car, the better it will perform aerodynamically. If you can control that air, you can use it to your advantage for downforce. But basically, if you can make the car as tight as we’ve been able to make it with the very special packaging tricks we’ve used, especially around the engine bay and the exhaust area, the car can really start to look like a lean, fast animal.

You don’t see fat animals that are fast... I have designed race-orientated production cars before, the Ferrari FXX and the Maserati MC12, but this is the first car with cutting-edge technology. This is the first car that I’ve had to work on the philosophy of a racecar with registration plates on it.” If the P1 really is, then, a racecar for the road, how will it feel to drive, and will the average owner of this million-dollar-plus hypercar even be able to drive it near the limit?

Stephenson has an interesting answer: “The P1 should make the driver feel that he can’t find the limits of what the car can do — that will always be a mystery. If you can dominate the car then you feel superior. The car is like a horse — if the horse allows you to do what you want to do but still has a lot in reserve, then it gives you more confidence to feel like you can go to the ends of the earth and push it to its very limits and it won’t be more than it can handle.

That means it should make you feel you’re a better driver than you are because it can take care of the difficult instances; it can make you feel comfortable when you’re in normal mode. But from a performance point of view, you shouldn’t be able to find the limits of the car; I think it should always be there in enough amounts to make you feel like you’re being taken care of in a certain way.”

McLaren seems to believe quite confidently that the P1 is creating a whole new class of hypercar — one beyond your mere Huayras, Veyrons and Venoms. This no-compromise design was also created to be not just a showcase of McLaren’s performance capability, but also to build upon the image of this youngest of carmakers as well — naturally as you would expect from McLaren, the P1’s design ethos is clean, concise and minimalistically focused.

“Believe it or not, the P1 was not difficult to design. When you design a car, you start with what’s called an engineering package and that decides the ultimate weight balance between front and rear, ultimate seating position and the wheelbase and all the dimensions that are basically the chassis of the car. “From that chassis you pretty much know the points that you can’t move like the suspension, the lights and different points like that.

So from a design point of view or a surfacing point of view, the best way to describe the car is: imagine we take a cloth and drape it over all of these points on the car, respecting these hard points that you can’t move and allowing it to settle — and that became the shape of the car. We added holes to the cloth where it was most efficient to get the air in and out and created a shrink-wrapped look, which relates to our design philosophy of minimalism, giving a lean, fast look.

“In racing you have to be very honest, you can’t fake-design on a racing car, what you see is what you get pretty much. Biomimicry is honest design; it is design with a purpose, much like it is in nature and it is always for the benefit of the species’ longevity — trendy doesn’t come into play. Nothing is there that does not need to be there, so we’re relying on the basic principles of performance through an evolution of what works best.

That in itself is timeless because you don’t worry about things being out of fashion from one year to the next, what works is beautiful and that is a very unused design language today. I don’t know anybody who uses that kind of inspiration for their automotive design language.” So how do you improve on something like the P1? Where to from here? Have we reached the zenith of hypercars?

Stephenson thinks we’re only just getting started. In fact, if he gets his way, the P1’s successor could make the same kind of technological leap that the F1 made in the Nineties, and the P1 is about to make later this year when McLaren celebrates its 50th anniversary in September and the car is officially released. “Money is no object, the ultimate McLaren would have the characteristics of a chameleon. I’d never have to settle for the same colour car every day.

The colour of my car could change by the colour of my mood. So on one day, I can have a yellow car when I’m happy, or even a grey colour when I’m serious. If I’m tired, the car can continue on its own or when I’m wishing to push the car to its limits, a seamless transition. “In terms of performance, it would be a car that is exhilarating, but does not depend upon non-renewable sources of energy so that you don’t need to worry about the economy of the car and ruining the environment.

“I’d like a lengthy choice of infotainment within the car — I could be kept up to date with social media, a car that allows me to interact in ways that have not yet been thought of as we enter an age of new forms of communication. [I would want] control of how my car sounds, ease of access and egress to the car, a pure canopy with no obstruction to the pillars, and finally, suspension that allows you to feel the downforce while maintaining comfort and security.”

It sounds like an impossibility. As if he were speaking about a 2020 McLaren hypercar, but don’t make the mistake of betting against Stephenson and his colleagues.