When architect and designer Georg van Gass was commissioned to build a second dwelling on a sprawling family property in an upmarket Johannesburg suburb, he was tasked with creating a structure that would nestle into the ground’s natural rocky ridge – remaining hidden from the main house, yet exploiting the views across the canopy of the world’s largest man-made urban forest.

The site came with specific challenges, which included building consent and size restrictions, but rather than limit Georg’s design, these two factors informed the creative and construction processes. “When we walked around the ridge’s rocky outcrops looking for potential sites, I realised I wanted to put the house on stilts, to almost have the house ‘float’,” he explains.

To do so, he conceived a raised structure made from plinths and columns, which would minimise the need for large volumes of concrete, because one of the problems with the secluded nature of the site was getting a truck to the location. This also provided an additional practical benefit as it meant the underside of the house could be used for services and utilities that, otherwise, would have taken up precious living space.

Working with the owners’ vision of a “glass and steel box”, Georg began looking at pavilion references including Philip Johnson’s Glass House and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. “I wanted to adapt these concepts to a South African context,” he says. “We were governed by size, so the design had to be compact, but still feel big. The question was how to interpret that.”

To achieve a real sense of inside-outside living, Georg worked with the sitting room and main living spaces as if they were patios. “A lot of people get it wrong in my opinion – they put a covered patio in front of their lounge and effectively block off the internal living areas, which can leave the interior feeling dark and cold,” he believes. He overcame this by ensuring that the central lounge, dining room and kitchen space would be simultaneously enclosed and exposed by a series of floor-to-ceiling glass doors and windows on two sides, designed to maximise light and allow efficient ventilation.

The concept of the design also meant dispensing with a few other conventional notions. “There is no real front door,” Georg points out. Instead, to create a sense of arrival – and to screen off the house – he designed a stone wall that is held up in a steel truss and frame. The granite was entirely harvested from the site, introducing warm, rough textures that play off against the building’s cool, clean lines.

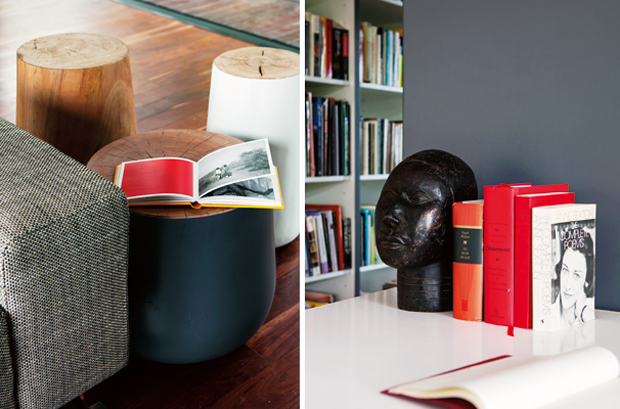

He also incorporated additional natural elements and textures into the dwelling with solid wood floors made from Zimbabwean teak – the only concrete flooring is found under the bathrooms – and freestanding timber designs from his own furniture range, Goet. All joinery items, including the kitchen island, the scullery and all storage modules, were custom designed for the space. “I’m quite old-school,” says Georg. “I don’t just focus on the structure. I think about everything in the house. How the floors meet the walls. Where the cutlery goes…”

To maximise internal storage, Georg integrated built-in cupboards and bookshelves into the depth of the stone wall structure. In the kitchen, he provided storage space under the central island and – because of the effective open-plan nature of the kitchen-living section – created a simple cupboard-like mechanism that would allow the potentially messy scullery and work area to be quickly closed off and hidden.

The design of the pavilion creates a space that, depending on your approach, is either hidden or transparent. Georg’s preference for simple,

well-made design solutions has allowed the building’s focus to remain on its spectacular environment – from the enclosed aspect of

the natural rocky outcrop and trees to the

broad expanse of suburbs and sky.