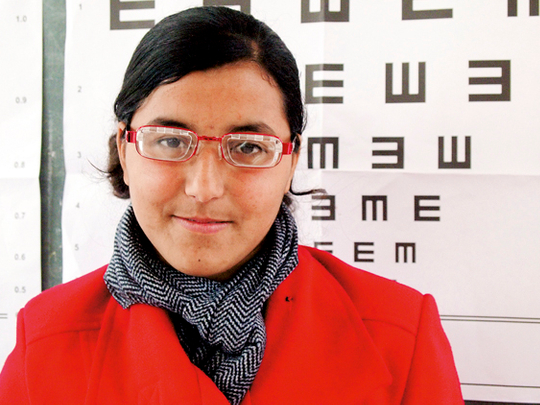

As the shadows lengthen and the sun’s heat fades, the men and women waiting patiently in line in Oujda, Morocco, move steadily forward. Perhaps for the first time in their lives, they will look at the black and white eye chart and attempt to read the bottom line before being handed a simple and cheap solution to a lifetime of sight problems: a pair of self-adjustable glasses.

For most of the students who turn up early the next morning to Badr Chakiri’s high school English lesson in Outat El Haj, Morocco, it’s just another day in class. But for a handful of students, it’s a new day: for the first time, they can see the blackboard clearly thanks to their Eyejusters glasses. “A pair of spectacles can improve how much a student learns by as much as 25 per cent,” says Peace Corps volunteer Philip Eubanks.

“And with an illiteracy rate as high as 44 per cent in the Kingdom of Morocco, it’s no surprise that both the monarchy and the United States Peace Corps would call for innovative ways to ameliorate at least one solvable issue in the fight against illiteracy: poor vision.”

Self-adjustable glasses are now becoming a reality through much of the developing world and bringing an end to sight problems in poorer areas – as well as a cheap, off-the-shelf option for people in richer countries. Using unique SlideLens technology, which even a child can adjust accurately, the glasses are a simple solution to the problem of a lack of qualified optometrists in much of the developing world.

According to the World Health Organization, some 670 million people worldwide live without the glasses they need. In developed countries, each optometrist serves under 10,000 people, but in parts of sub-Saharan Africa there is one optometrist to serve one million people. The annual cost to the economies of the developing world of having so many people who cannot see properly is $400 billion (Dh1.5 trillion).

Overcoming barriers to work

Offering people in developing countries a simple, low-cost pair of glasses they can adjust and re-adjust themselves is key to overcoming barriers to work and education caused by poor eyesight, according to an Oxford-based team that has just launched the glasses.

Each SlideLens is made of two pairs of lenses. When these lenses are slid over one another, they act like one lens and can be adjusted depending on how much magnification a person needs.

The advantages of using sliding adjustable plastic lenses are easy to see. They are durable, reliable and economical. SlideLens beats existing liquid-filled adjustable-lens technology by creating durable, self-adjustable glasses that are as close as possible to normal glasses.

Each pair retails at about $40 in the United States and they are subsidised in several developing countries including Bangladesh, India and Morocco.

Launched in April this year, Eyejusters was inspired by the work of Professor Josh Silver, an atomic physicist who heads the Centre for Vision in the Developing World in Oxford, UK, and launched AdSpecs, which created simple liquid-filled glasses a decade ago to help those without access to an optometrist.

After developing AdSpecs he realised he could adjust the lenses to correct his own short-sightedness.

Making self-adjustable glasses on a large scale was key to creating what Josh calls, “universal” glasses. “It’s one of the world’s biggest problems,” he says. “There’s an

immense amount of interest in solving it, and self-refraction is one route that can

assist with that.”

The ground-breaking project has been updated, and the round liquid-filled frames have been superseded by Eyejusters, an organisation that makes glasses in stylish metal frames that can be adjusted as people age, their vision changes or to share with their family.

“Allowing people to set their own glasses without the need for highly trained optometrists allows them to get just the glasses they need,” says Owen Reading, one of the co-founders of Eyejusters. “Easily correctable refractive error means far more than poor vision – it can blight a person’s life and destroy education and job opportunities, and reduce their productive lifetime and quality of life.”

Eyejusters has just completed a major trial at ten sites in Morocco. “The country has basic healthcare, but is still very lacking in optometric provisions, which made it a good test case,” says Owen.

“It is perhaps better than a sub-Saharan African country where the needs of the people are often a lot more desperate than needing a pair of glasses.” Driven forward by Peace Corps volunteers Philip and Caity Connolly, the trials in Morocco have had a huge impact.

“A pair of self-adjusting and continually re-adjustable glasses means that a person with vision problems might never need to visit an optometrist to correct their sight,” says Caity. “They will only need one pair of glasses for the rest of their life, despite a potential deterioration in vision.

“Literally, a small turn of a knob on the side of the lenses and someone can go from an inability to read the top line of a sight chart to the level of sight considered legal to drive in the UK. Few things in life are so instantly rewarding.”

Self-adjustable glasses are transforming lives. “It’s a very humbling experience when someone turns the dial and can see clearly for the first time in their lives,” says Owen. “We did a project in Liberia where a number of us trained and worked with local volunteers providing glasses in rural and urban areas.

“One of the people we helped was Arthur, a father of nine who had recently lost his wife. He was 57, and his loss of vision was beginning to affect his work as a carpenter. A pair of self-adjustable glasses helped him to get 20/20 vision once again, prolonging his productive life and helping him to support his family.

“Another person we helped was Emmanuel, a 71-year-old who had never been able to see things at a distance clearly. He had also recently lost vision in his right eye. Once he put on the glasses, his face lit up when he changed the lens to see distant objects properly for the first time in his life. He said to us, ‘You’ve made me

a few years younger’.”

Reaching huge numbers in remote areas of the developing world means working with commercial partners to fight poverty as well as poor vision.

Eyejusters hopes to work with NGOs and commercial retailers in the UAE, especially those with links with India or who wish to support micro-entrepreneurship schemes.

“This has the potential to be a real game changer in eyewear provision,” Owen says.

“It’s important to emphasise that in South Asia we see our glasses as an ideal micro-entrepreneur product. They’re light and small to stock, unique, can be dispensed by almost anyone and provide a vital service in areas without optometry services.

“We’re interested in working with micro-entrepreneurship organisations and distributors to local and mobile retailers in these parts of the world.’’

The perfect reader

It’s not just in remote areas that people need glasses. “After selling reading glasses for over 20 years, we know there are numerous situations where one person would need varying strengths of lenses – reading at the beach versus dim light in a restaurant, different sized texts, and especially reading the computer screen versus something on your desk,” says Farrell Burk at Debspecs.com, an eyewear accessories retailer that donates a portion of sales to Eyejusters projects worldwide.

“And some people in wealthy countries are left out of the over-the-counter reader option because one eye is a different strength than the other. Eyejusters solves this because each eye can be focused separately.”

But for people in the developing world, Eyejusters’ Give & Get programme provides a free pair of glasses to someone in need for every pair sold through its website.

Lars Iversen, co-founder of Karmoie, a Norwegian designer sunglasses brand, which donates a pair of Eyejusters to people in the developing world for each pair of sunglasses it sells, believes that these glasses change lives.

“There is an enormous need,” Lars says.

“A major bottleneck is the shortage of trained opticians and optometrists to diagnose refractive error (whether it’s myopia, hyperopia or astigmatism) and dispense glasses. We wanted to help people by empowering them.”

Lars travelled to South Sudan in July 2012 and met local people who needed glasses including a 13-year-old girl. “She had a lazy eye and suffered from severe refractive error,” says Lars. Though they couldn’t help with the lazy eye, she got a pair of glasses to help her see.

“The change would allow her to go to school and do most things other children do,” says Lars. “The difference for her is that instead of a life dependent on friends and family, she has a better opportunity to become independent.”

Eyejusters now works closely with international partners and trained local

teams to reach those who most need help.

“These glasses have made my reading clear,” says Andrew Taban, 29, a watchman from South Sudan. “Now I am able to read the smallest things and am very happy. Eyejusters is changing lives.”