Daniel Day-Lewis was riffing on the mysteries and curiosities of romantic entanglements — how people can be governed by desires that seem alien even to themselves.

“There’s no strangeness you can imagine that is more strange than the lives of apparently conventional people behind closed doors,” he said.

He was offering, with some provocation, a defence of his latest character — a brilliant, mercurial midcentury couture designer at the centre of Paul Thomas Anderson’s lush new psychosexual drama Phantom Thread.

But the observation could also serve as the thesis for the film as a whole. Set in 1950s London, it explores the borders between love and masochism in a distinctly Andersonian twist on old Hollywood gothic romances.

Given that Day-Lewis has announced, at 60, that this will be his last performance — despite having won the Academy Award for best actor twice over the last decade (bringing his total wins in the male category to a record-setting three) — he was a convincing messenger.

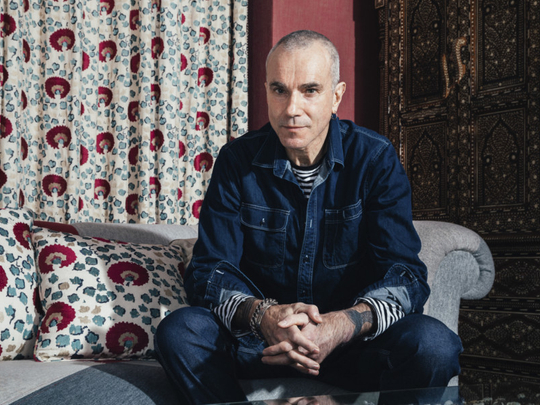

“We can’t begin to know,” why people make the decisions they make, he said in a hotel parlour in lower Manhattan, leaning forward on an embroidered sofa in crisp jeans and a striped sweater, “but it works for them.”

In conversation, Day-Lewis speaks in a measured, halting cadence with a delicate, slightly hoarse tone that would shame the most impudent interlocutor into silence. The effect is simultaneously dominant and recessive, like a mountain made of glass.

He is once again the subject of Oscar buzz this season — and was nominated for a Golden Globe — for his performance in Phantom Thread as fictional designer Reynolds Woodcock. If the film is more precise in scope than Day-Lewis’ most recent vessels, including Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln and There Will Be Blood with Anderson, the role is no less indelible — a searing and unexpectedly comic portrait of corrosive genius.

On a recent morning in December, Day-Lewis and the film’s other stars — British actress Lesley Manville, who appears as Reynolds’ imperious sister and business manager, Cyril; and Luxembourgian actress Vicky Krieps, who plays Alma, the designer’s headstrong muse and love interest — were gathered to discuss the film as a trio for the first time without Anderson present.

Asked directly, Day-Lewis declined to explain his decision to retire, which he disclosed this summer and which his co-stars said they had no prior knowledge of during filming. “It’s a decision made with conviction, but not full understanding,” he said.

He spoke reverently of his experience making Phantom Thread, which grew out of years of creative collaboration with Anderson. Day-Lewis, who is known for thoroughly immersing himself in a character before setting foot on set (he built canoes while preparing for The Last of the Mohicans), apprenticed for nearly a year under Marc Happel, costume director of New York City Ballet, to transform himself into Reynolds — a control freak with a monomaniacal zeal for dressmaking largely based on real-life fashion forefather Cristobal Balenciaga.

He studied drawing, hand sewing and draping, ultimately sewing 100 buttonholes and remaking a Balenciaga sheath dress from scratch. “I’ve explored so many different worlds, but the thing they have in common is they were always entirely mysterious to me in the beginning,” he said.

That is “probably a great part of the allure — discovering something that seems beyond reach, sometimes impossibly beyond reach, that pulls you forward into its orbit somehow.”

What became Phantom Thread was originally conceived around three years ago while Anderson was briefly bedridden with an illness. More dependent on the care of his partner, actress Maya Rudolph, than usual, he outlined a story about an intensely intimate relationship between a man, a woman and his sister. Later, after Anderson picked up a biography of Balenciaga in an airport, the man in his story became a master designer with a monastic lifestyle that is disrupted by new love.

“Clothing designers in general have reputations of being controlling, exacting, demanding,” the director, an unlikely fashionisto, said in a telephone interview. “Those traits are very, very helpful for our character.”

Anderson is an admirer of suspenseful romances like Rebecca (1940) and Gaslight (1944) and pictured Day-Lewis as a darkly debonair leading man in the mold of Laurence Olivier.

The two men also developed a mutual fascination with Balenciaga, who had a reputation for being utterly consumed by his trade.

“His attack on his work was very relatable to me,” said Anderson, whose earlier films include Boogie Nights and Magnolia. “I’m kind of a hobby-less person — the only hobby I have is making films — so I could relate to his passion and single-minded preoccupation.”

Does that mean that Reynolds is a thinly veiled alter ego? Anderson batted away the suggestion.

“I have filthy work habits,” he said, comparing himself with the character, who keeps a pristine workspace and a rigid schedule. “And I have four children, so it’s usually chaos.”

For Alma, Anderson sought a European unknown and found Krieps (pronounced krehps), 34, whom he’d seen in the German black comedy The Chambermaid (2014). Day-Lewis championed Manville, 61, for the part of Reynolds’ sister Cyril. Discussing how they were cast, the actresses accidentally uncovered a potentially awkward disparity.

Manville, who has appeared in several films by British director Mike Leigh, expressed relief at how easy the process had been for her, and bemoaned the way many actors are forced to audition for roles today. “They’re playing scenes by themselves and recording them on their phones,” she said.

“It just seems ridiculous — it’s a ludicrous way to judge anybody.”

Krieps, shooting a glance at Day-Lewis as Manville was talking, interjected. “But that’s how you judged me!”

Such inequities, it turns out, had some strategic value. In Phantom, Krieps’ character is a youthful insurgent — a spunky waitress-turned-muse who destabilises the fine-tuned equilibrium between Reynolds and Cyril. Day-Lewis and Anderson deliberately fostered that dynamic off camera, hoping to conjure movie magic once it was rolling. There were no rehearsals, and while Day-Lewis and Manville spent months cultivating a familial rapport by getting lunches and exchanging phone calls, Krieps was discouraged, at the request of Day-Lewis, from interacting with either of her counterparts until the first day of shooting. “I tried to be like a monk,” she said of preparing for the role. Before shoots near the northern English coast, she would ease her anxiety by taking long walks and meditating to the sounds of the ocean. “If I allowed myself to have any ideas about acting or who they were, I would have been very, very scared.”

Krieps’ nervous energy comes through on screen. In a pivotal early scene, when Reynolds first meets Alma in a diner, she stumbles and nearly drops an armful of dishes before catching her balance and flashing a charming, sheepish smile. Reynolds, watching from afar, finds himself smitten.

“That’s the real thing,” Anderson said, explaining that the fateful stumble wasn’t written into the script. “And her blushing is not a visual effect.”

In the movie, Reynolds sweeps his clumsy Cinderella into a world of opulent dresses, extravagant dinners and literal princesses. But the story is no fairy tale — at least no more than There Will Be Blood is a western — and their relationship becomes more perilously charged as the plot builds toward its surprising climax. In one of the few scenes in the film to contain improvised dialogue, Day-Lewis’ character berates Krieps’ character over the proper way to cook asparagus. Anderson said he hadn’t anticipated how far the actors would take it. “It just kicked off and they started tearing each other’s throats out a little bit,” he said.

In previous films, including Punch-Drunk Love and The Master, Anderson has eschewed traditional, hand-in-glove romance narratives, lingering instead on the idiosyncratic nature of relationships and holding a microscope to the secret, contradictory roots at their foundations. With Phantom Thread, he has created his most unflinching — and likely most provocative — love story yet.

“In my experience, and the experiences that I’ve seen of the people around me, there is a never-ending shift of power in a relationship: Who’s driving? And who’s criticising the driver?” the director said. “That’s kind of a natural thing that we all deal with if we decide to share this life with somebody. In the movie, we just crank it all up to 10 as a way to highlight and underline it.”

Of his co-conspirator, Day-Lewis, Anderson said he was trying not to think about the possibility that they will not work together again, and that he may have presided over the actor’s last performance.

Asked what he will miss most about Day-Lewis, he said, “He’s an actor and a movie star, and movie star isn’t a negative — movie star means that when you sit down in a theatre, the lights go down and the big screen opens up, you have somebody who can fill that space.”

Then he paused. “[Expletive]. I don’t know,” Anderson added finally. “He’s just a giant.”

___

Don’t miss it

Phantom Thread releases in the UAE on February 1.