They say the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. In Pakistan, it seems the average entrepreneur’s heart is set on the stomachs of others. The restaurant business is tremendously popular in the country, and it doesn’t seem to be letting up either. Most industries, from flowers to new homes, witness booms, bubbles and busts. Food, however, has a distinct viability in Pakistan. By some estimates, Pakistanis are spending over Dh3.65 billion on eating out every year.

Urban areas are now home to nearly 70 million people, over a third of the entire population. This demographic is growing in size and pocket, with the middle-income distribution fattening at a considerable pace. Most of these people have little other than restaurants as a source of entertainment on account of the country’s customs and laws. Restaurateurs have hence enjoyed long term success, with the landscape of eateries now more diversified and dynamic than ever before. Food is an important sector in the country’s economy, and like the larger economy, it faces bottlenecks of its own.

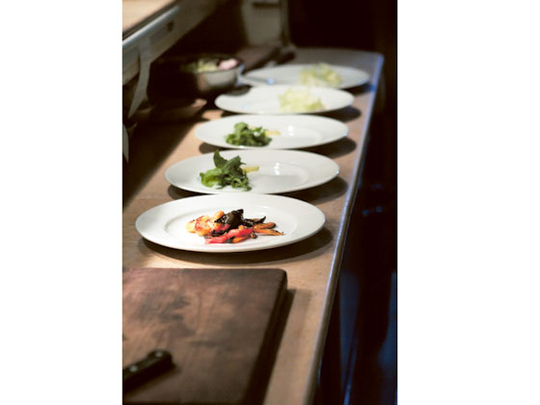

Fine dining trend

A new wave of cookery shows are encouraging young people to take an interest in gourmet cooking. This is also, in many ways, responsible for creating and popularising the fine dining concept. However, fine dining is somewhat of an enigma in Pakistan. City streets are strewn with relics of failed businesses that attempted to tackle this space. Some say upmarket cuisine is not popular with the general population — to whom subtle flavours and spoon-sized portions are an alien concept. There are a handful of anomalies, however, that have made it, including a critically acclaimed, snug Mediterranean spot on Karachi’s Zamzama high street — Okra.

Owner and chef Ayaz Khan started this restaurant 13 years ago. Describing the limitations that have accompanied the success of the concept over the years, he says, “It’s intense. I’m the only one here and it has to be that way. There is an HR issue here — if it isn’t an issue of competency it is one of trust. There is no ready market of trained staff and there are inherent risks in investing time and money in training someone due to high employee turnover in the country.

“We always thought about expanding to show some growth. A lot of people have approached me as investors. In the end I always thought it couldn’t happen because of the kind of food we are serving — what we do here is difficult. I’ve come to accept that it is physically impossible to open another restaurant.”

Initial success

The adage “if you want something done right you have to do it yourself,” is pertinent for this industry as it is difficult to expand even if one is successful. But how does one even achieve initial success? “Pakistanis are very discerning people and demand value from any service. Our customer base is well-travelled and can appreciate value in subtle packages. But even a place as established as Okra cannot depend on one demographic. We are a mix of a bistro and fine dining setup. There is a special lunch menu with Pakistani dishes, gourmet burgers — middle market products. Even though this is generally the local taste, there has been a greater emphasis because of recessionary pressures. A lot of restaurants have refocused their strategies, and the middle-range outlets are doing very well.”

Creative strategies

Ayaz stresses the importance of getting the basics right, including the need to have the right produce, which is not easily available in the country. About 40 per cent of Okra’s ingredients are imported from Dubai. “Everything is available in Dubai, and the technology exists so restaurants no longer have to import frozen items. It makes a big difference to the dishes that the salmon and meat I order for example, comes chilled,” says Khan.

In Lahore, a group of eateries that operate on similar principles have been enjoying some of the greatest success of any restaurants in the upscale space. Mikail Khan is a Director at the family consortium that runs the Cosa Nostra group of restaurants in Lahore. These include Cosa Nostra, an Italian spot; the Delicattessen, a sandwich bistro and Gelateria, a gourmet ice-cream shop. “Cosa, our main restaurant, is bifurcated into two sections — La Tabola, the fine dining section and La Pizzeria, the casual bistro. Although both do well, it is La Pizzeria which is more financially successful. In the restaurant business in Pakistan, the emphasis has to be on affordability and value if one is to grow. Whatever the strategy or theme, success still depends on being able to handle two key issues — quality ingredients, and quality staff. Both are in low supply.”

Mikail, however, suggests that there are no limitations as to what concepts could work in Pakistan, if executed well. “Enough of the population is open to new ideas and imaginative food. If you can handle the bottlenecks and produce good food at a decent price, you’ll do well, regardless of what type of food you serve.”

That is a view that may not be shared by Islamabad-based Sharez Aziz, who recently shut down his first venture, a Mexican restaurant, Salsa, after just under a year of operations. “A lot of people speak of the fact that there is no well-known Mexican outlet in Pakistan. Those who have spent time in the US usually crave it and there are significant numbers of such people so it made sense to open a place that serves good Mexican dishes. Many people have a good idea and think they can create a decent side income in this burgeoning market. Running a restaurant is a full-time job, especially in this country. If you are not on the ground handling things, everything that can go wrong will go wrong. I saw Salsa as an investment, but it required much more than simply that.”

Starting a restaurant in Pakistan is almost down to execution. The country’s wealthiest restaurateurs are those who handled simple concepts with business efficiency, and scaled them into multiple units. Perhaps the richest — owner of BBQ Tonight, a chain of restaurants serving staple Pakistani dishes — started off as a roadside vendor peddling kebabs and tikkas. Dubai is also now home to two of his restaurants.