The venue is a home in Dubai. The occasion — an informal gathering of music lovers to welcome visiting artists Ustad Maqbool Husain Khan and his sons, Zeeshan and Zohaib Khan. The three are to perform the next day at the last in a series of four Indian classical music concerts organised by Saffron Media.

The presence of a piano in the hosts’ living room prompts the brothers, seventh-generation Indian classical musicians, to set up an impromptu concert.

The setting is free from the usual trappings of concerts, without even a microphone or amplifiers. Sitting on a straight-backed chair, dressed casually in jeans and a red hoodie, Zeeshan — whose travels in 2012 include a trip to Bach’s birthplace in Germany, where he sang at a fusion concert — is confident of his voice and craft.

“We’ve never jammed on a piano before,” he says, pausing midway through a traditional composition, probably tuned to the complex notes of raga Kafi by the founder of Rampur-Sahaswan gharana, their school of music, 100 years ago. Zohaib is trained in both Western and Hindusthani classical styles.

The audience breaks into applause and praise each time one of the brothers displays mastery over a complex phrase, vocally or on the piano. A spectator records the session on an iPad and one can be sure this will be added to Zeeshan’s collection of clips on YouTube.

A couple of songs later, an enthusiast from the audience — an Emirati who sings in Hindi — joins the session, bringing a Bollywood medley into the mix. Zohaib, who also enjoys a thriving Bollywood career, is ever the sporting genius and gamely continues accompanying on the piano.

The evening encapsulates the contemporary avatar of India’s classical music, performers of which have always had a finger on the pulse of the audience. They carry the gravitas of being inheritors of a pure, centuries-old tradition of music. They are trained much in the same way as their forebears, starting to learn music at age three or four. They practise about four to five hours a day on an average, with ancient instruments and ragas.

They will also routinely pepper any concert with pithy one-liners, simultaneously inspiring awe for their music and converting even less knowledgeable listeners into lifelong fans. Only now, the younger generation, often armed with additional, non-music degrees, is conversant with what YouTube can do.

New audiences

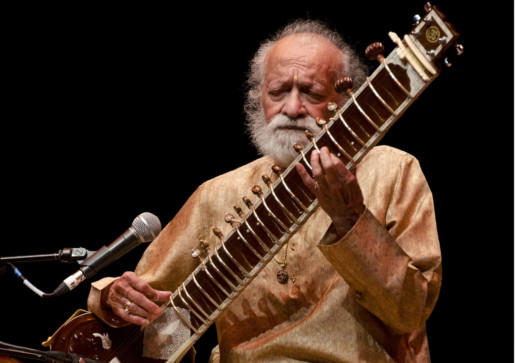

In 1971, the late sitar maestro Ravi Shankar set the tone for interactions between Indian musicians and non-Indian audiences. At a concert organised by friend and Beatles guitarist George Harrison at New York’s Madison Square Garden, he had responded — tongue firmly in cheek — when the audience started applauding at the first few chords, “If you like our tuning so much, I hope you will enjoy the playing even more.”

In the hallowed circles of classical music, the story is recounted like a lesson to younger ones learning to perform for audiences who may not be familiar with their music.

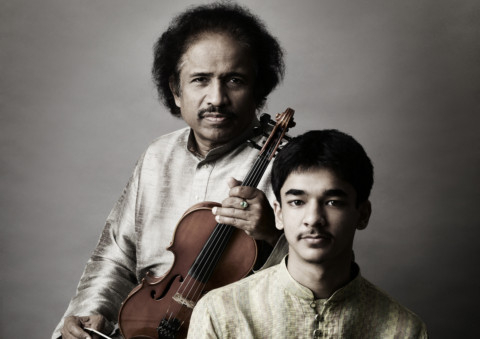

Ambi Subramaniam, the 20-year-old son of the famed violinist, composer and conductor Dr Lakshminarayana Subramaniam, says that while the means of connecting with the audience may be new, the method is old.

“We have that system where there is no barrier between the audience and the performer. If they like something they will let you know,” the younger Subramaniam, who — like his father — is trained in classical Carnatic music, tells GN Focus.

“It makes us and the audience more comfortable, unlike Western classical music, where any kind of sound or movement by the audience is forbidden. We are used to interacting,” says the young performer, who is getting to be as famous as his father and boasts 10,254 likes on Facebook.

Suvir Misra, who plays the rudra veena, an ancient instrument whose popularity has seen a relative decline since the early 19th century, says technology is a friend. “I am imparting technical lessons to some students using Skype,” he tells GN Focus.

“Digital communication is now an adjunct to a traditional training. The hours of practice or riyaaz remain the same, but with technology one can plan the performance sitting anywhere, while listening to the tanpura or tabla machine on the iPhone or a tablet. Earlier, a musician needed two students to carry the tanpura. Now, my accompanist comes once a week.”

Jamming, as Zeeshan demonstrated, can take various forms and is quite a tradition in itself. Ambi’s father has collaborated with musicians including Yehudi Menuhin, Stephane Grappelli, Ruggiero Ricci and Jean-Pierre Rampal.

Ambi now joins him for various concerts, such as the one organised in August at the Lincoln Centre in New York with jazz fusion guitarist Larry Coryell and blues-fusion harmonica player Corky Siegal.

Amit Pateria of Saffron Media tells GN Focus that not only has the digital medium changed the way people listen to music, but performers are also discovering newer ways of interacting. In India, classical musicians are increasingly associating themselves with to initiatives such as MTV’s Coke Studio.

In Dubai, Pateria not only brought the performers down for the Emirates NBD Classics events throughout the year but also organised workshops while they were here. “The digital medium has changed the way people listen to music, conceptualise or have perceptions on it. Musicians have their own channels. Performers tell us to record concerts and put them up right away. They are by major music labels, their copyrights are protected anyway, so there is a huge change in the way publicity is managed,” says Pateria.

More publicity

Furthermore, Indian classical music, having thrived through royal patronage and then state support, is finding that music as a commodity differs in each century. Misra says Indian classical music cannot compete with commercial releases of popular music.

“The maximum revenues from popular releases are gathered in the first three months of the commercial release. I cannot see this happening with classical music where audiences do not purchase on impulse, relying more on music reviews, peer reviews and word-of-mouth publicity before deciding to buy,” he says.

“The only utility I can see of these digital releases would be in promotion,” says Misra. “Classical musicians would probably be able to sustain themselves from the concerts, teaching, workshops, collaborations and other live events.”