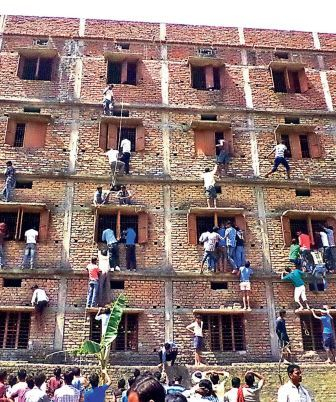

India’s highly competitive education sector has had something of an annus horribilis. In what could be a plot for a Bollywood movie, images of family members helping students cheat during school-leaving exams in Bihar went viral first, and then others were caught cheating during medical school entrance exams using high-tech devices.

The Bihar incident in March made headlines around the world, followed by a Supreme Court ruling in June that 630,000 students retake the All India Pre-Medical and Pre-Dental Entrance Test for the 3,800 coveted medical seats. According to reports, the latter was the 12th such national exam marred by allegations of cheating in as many months.

A four-month Reuters investigation, also published in June, found that more than 16 per cent of the country’s 398 medical schools have been accused of cheating through tests and bribes, according to both Indian government records and court filings.

More recently, the Central Bureau of Investigation, India’s intelligence agency, has been assigned to investigate a $1-billion (Dh3.67 billion) college admission and government job recruitment scam called Vyapam. Dozens of senior officials have already been incarcerated and nearly 2,000 others questioned. The scandal has also been linked to dozens of suspicious deaths.

We cheat because we can...

Many blame this cavalier attitude to cheating on lack of access to higher education, with top institutes reporting acceptance rates as low as 0.1 per cent. D.S. Rawat, Secretary-General of the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry (Assocham), claims Delhi University has raised its admission grade requirements to 100 per cent for some degree programmes. The organisation also found that a prospective student has a one-in-50 chance of securing a place at one of the 18 prestigious Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs).

This leads the rich to bribing their way in and others to cheating to level the playing field. “It is our democratic right!” the BBC quotes one, Pratap Singh, as saying. “Cheating is our birthright.”

Explains Arun Kumar, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, “Today, there is no need or want to excel among students. They and their parents want degrees at any cost — not education,” he told the Hindustan Times.

Some educators identify flaws in the national education policy implemented in 2010 which coddles underperforming students and doesn’t train them to take tests. “They are used to passing [tests],” Madhukar Yadhav, the headmaster at Balmohan Vidyamandir, told the LA Times last year. “They don’t become accustomed to studying.”

According to Assocham, Indian higher education institutions and IITs lose $6 billion to $7 billion annually as more students opt to study abroad. It found that some 680,000 Indians went overseas last year for further education, up from 290,000 in 2013. “A minuscule number of them choose to return home,” the association says in a statement.

Digital strategy

Many educators are calling for the abolishment of rote-learning, which would eliminate widespread cheating since exams would test students’ grasp of concepts, rather than their memory. Others believe a push toward digitisation will mitigate the situation while also giving more students access to learning.

Concurrently, this strategy is more congruous with the digital lives millennials lead. Digital is the default in the global economy and exposing students to that will benefit India’s economy.

According to Tata Consultancy Services’ TCS GenY Survey 2014-15, Indian school students are rapidly adapting to digital lifestyles. “Today’s high-school students lead gadget-rich lifestyles, are heavy internet users and active on social media channels to stay well informed [about] current affairs and keep in touch with family and friends,” the recently published study states.

Sugata Mitra, Professor of Educational Technology at the School of Education, Communication and Language Sciences at Newcastle University, is an advocate of this strategy. “Let students use the internet in exams,” he has been quoted as saying while commenting on how to reform India’s education system.

“In doing so, the whole system would have to change. The kind of questions set in exams would have to change. You can’t ask, for example, simple factual questions, because they would be too easy to answer. The questions would have to be framed instead to probe students’ understanding of concepts and principles. Educators would also have to teach differently, just as officials would have to rethink the school curriculum.”

This thinking is in-line with the Modi government’s adoption of Digital India principles, initiated by the previous administration. “[Higher education institutions] must deploy technology to efficiently disseminate academic material to greater number of students, engage [stakeholders] through e-platforms and establish links with research and other academic institutions,” President Pranab Mukherjee said recently.

“Though India’s higher education [system] is the second-largest in the world, the enrolment rate of 20 per cent is not enough to improve future prospects of the youth and harness opportunities in an increasingly knowledge-intensive world.”