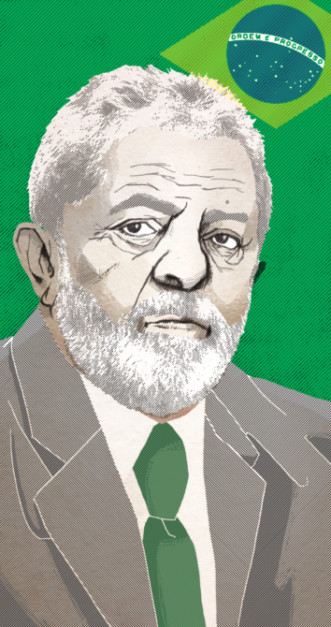

It took Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva four attempts before he was finally elected as Brazil’s president in 2002. He came to office as the first leftist leader in Brazil in nearly half a century. And he left eight years later — barred from standing for a third term — enjoying exceptionally high popularity ratings for retiring Latin American leaders.

His 2002 election victory marked the end of an unprecedented journey — from abject poverty to the presidency of Brazil. Da Silva came to power promising major reforms to the country’s political and economic system. He vowed to eradicate hunger and create a self-confident, caring, outward-looking nation.

Analysts say it is because of some of his government’s social programmes — which benefited tens of millions of Brazilians — that Da Silva retained his popularity. He raised Brazil’s profile on the international scene and presided over Brazil’s longest period of economic growth in three decades, they say.

Da Silva began life in humble circumstances. He was born on October 27, 1945, at Garanhuns, in the hinterland of Pernambuco State. Later on, as admitted by Brazilian legislation in the cases where a person becomes better known by a nickname than the real name, he added “Lula” to his name of birth. The name Lula, in Portuguese, means squid (the marine animal), but is also the nickname of many people called “Luiz”. Lula is the seventh of the eight children born to Aristides Inácio da Silva and Eurídice Ferreira de Mello.

In December 1952, the family travelled 13 days on the back of a truck (“pau-de arara”) and settled in Vicente de Carvalho, a poor neighbourhood of the city of Guarujá, in São Paulo State. Lula received basic schooling at the Marcílio Dias Public School. In 1956, the family moved into a bedroom at the back of a bar in the Ipiranga neighbourhood.

Da Silva worked as a peanut seller and shoe-shine boy as a child, only learning to read when he was 10 years old. His father was against education and believed supporting the family was more important. At age 14, Da Silva went on to train as a metal worker and found work in an industrial city near São Paulo, where he lost the little finger of his left hand in an accident in the 1960s.

Lula was not initially interested in politics but threw himself into trade union activism after his first wife died of hepatitis in 1969.

Elected leader of the 100,000-strong Metalworkers’ Union in 1975, he transformed trade union activism in Brazil by turning what had mostly been government-friendly organisations into a powerful independent movement.

In 1980, Da Silva brought together a combination of trade unionists, intellectuals, Trotskyites and church activists to found the Workers’ Party (PT), the first major socialist party in the country’s history.

Since then, the PT has gradually replaced its revolutionary commitment to changing the power structure in Brazil with a more pragmatic, social democratic platform. Before his 2002 election victory, Lula had previously lost three times and he began to believe his party would never win power nationally without forming alliances and keeping powerful economic players onside.

So his coalition in that election included a small right-wing party and he carefully courted business leaders both in Brazil and abroad. The Workers’ Party manifesto reflected its sometimes conflicting instincts.

It remained committed to prioritising the poor, encouraging grassroots participation and defending ethical government.

Reacting to the downturn in global and US markets in 2008, he said, “We can’t be turned into victims of the casino erected by the American economy.”

He was credited with helping Rio de Janeiro to win the 2016 Summer Olympics, the first Olympics to be held in South America.

In his time in office, Lula pumped billions of dollars into social programmes and can reasonably claim to have helped reverse Brazil’s historic inequalities.

By increasing the minimum wage well above inflation and broadening state help to the most impoverished with a family grant programme, the Bolsa Familia, he helped about 44 million people and cemented his support among the poor.

However, many commentators argue that the programme fails to address the structural problems that underpin poverty, such as education.

Rather than implementing radical left-wing reform, as feared, Lula adopted dark suits and a calm, pragmatic approach that allowed him to become a star of global diplomacy while reinforcing cooperation between the world’s developing nations.

The review “Foreign Policy” even went as far as to call him a “rock star” on the international stage who projected impressive charisma. US President Barack Obama called him “the man”.

A gifted negotiator, Da Silva knew how to build unlikely alliances or cast off friends who had suddenly become liabilities.

There is also some criticism of the country’s economic performance under Da Silva. Although Brazil saw steady annual growth, some business leaders argue it lost the competitive edge against international rivals. Nonetheless, his government quelled fears in financial markets by keeping the economy stable and achieving a budget surplus.

In April 2010, he was voted number one of “Time” magazine’s 100 Most Influential People in the World for 2010.

Da Silva regularly gives speeches about his belief that global institutions such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organisation favour rich nations and must be revamped to address the needs of developing nations, where most of the world’s population lives. Longtime friend of Fidel Castro, Da Silva visited him in September 2003. Castro backed all of his presidential runs.

Da Silva was diagnosed with throat cancer in October 29, 2011, and underwent chemotherapy to treat a malignant tumour in his larynx.

Compiled from BBC, v-brazil.com and CNN.

This column aims to profile personalities who made the news once but have now faded from the spotlight.