The Principal of Bahia Grande School, one of the largest schools on the island of San Cristobal, Panama, is huddled with a group of three women - mothers who had volunteered to cook the school's daily lunch. Two boys had carried pots half-full of water up a hill from a well far below. The group of three mothers and the principal closely studied the water. One mother thought that it was too polluted and therefore not suitable for cooking, whereas the other two thought otherwise.

"We feel we can use the water,'' they said. All eyes then turned to the principal, who had to then decide on whether they could go ahead and cook the meal with the water or not. She studied the water for an agonisingly long minute, then turned to the women and gave her consent - they could go ahead and prepare lunch.

A student who overhears the conversation between the mothers and the principal is overjoyed when the principal gives his assent. He runs back to his friends to give them the good news - they will get a meal today - probably the only meal for the day. For 200 children, the principal's assent meant they would not have to stay hungry.

"This is the hardest part of the job,'' the principal later told Joe Bass and his wife, Maribel, tourists who had arrived at the school. "The kids are hungry and need to eat, but the food makes them sick [when cooked with polluted water]. I wish I always made the right choice.''

The scene was truly heart-rending and the Bass couple immediately decided to do something for these children. "We promised to put in two rain catchment tanks at that school the very next week," recalls Joe, in an exclusive email interview to Friday. "These tanks were the first installations of rain catchment water tanks in the area.''

Coming out of retirement

Not too many retired people would choose to live in a sparse house with few amenities deep in a remote forest infested with insects and reptiles. And fewer still would think of spending the evening of their lives helping people on a remote island find safe drinking water.

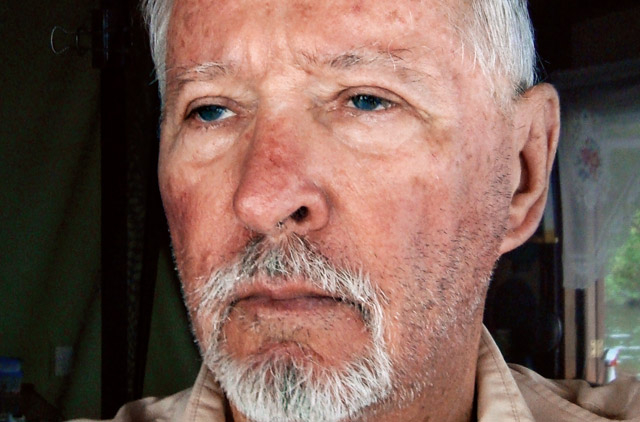

But then not many people are like Joe Bass. The founder of Operation Safe Drinking Water, he does not hesitate to muddy his boots if he thinks it will help a person, particularly a child, get a cup of potable water.

An American, Joe and his wife Maribel have been living on an island in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago of Panama for a couple of years now and are determined to makes a difference in the lives of people on the islands who have little recourse to pure drinking water.

But how did the couple come to know of the plight of people in the Archipelago?

Bass was in his early seventies when he and Maribel, residents of Costa Rica, Maribel's home country, decided to visit their friends who were living on an island in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago of Panama. Most of the residents of the island were indigenous people, cut off from the mainland and living in isolation and poverty.

It was there that Bass and Maribel came across a medical clinic run by a visiting medical worker from the US. The aid worker was busy treating a 13-year-old boy who was afflicted with a dreadful skin disease. The little boy was in agony and the medical worker could do little to help him. "See this boy?'' the aid worker said to no one in particular. "I treated him last year. I'm treating him now, and I'll probably have to treat him again when I return next year. Wondering how did he end up like this? It's all because of polluted drinking water. He has no alternative but to drink the foul water.''

But can't something be done to help the people, asked Joe. The aid worker turned to him: "If you want to do something to help these people, help them get safe water. They need that more than anything else."

The friend Joe was visiting had a rainwater catchment tank which was filled by the frequent tropical rains. Joe knew that water was clean and safe to drink.

"After our short vacation [if you can call it that] we returned to Costa Rica, but we couldn't forget the misery of that boy and what the medical worker said,'' recalls Joe.

"Soon after, we packed our bags and decided to give up our comfortable lives and work towards improving the lives of these poor people. After moving to one of the islands in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago of Panama about three years ago, we started doing whatever we could as a couple to help the people of the remote areas.''

Joe was a trained first aid worker and he realised that one of the areas where he could be of help was in lowering the infant mortality rate which was pretty high because of poor quality water that was given to them in their early years.

The water in streams get polluted by people and animals upstream. So by the time the water reaches people in low-lying areas, it is contaminated with faecal matter and animal waste. Also, the water collects in collection holes near schools and quickly becomes muddy and unusable, says Joe.

"The first thing we decided to do was launch a boat-based first-aid initiative throughout the islands. It was heartbreaking to see so many innocent lives being lost because something as basic as clean drinking water was not available," says Maribel.

"While Maribel helped people who were sick, I focused on prevention - setting up rain catchment tanks in schools,'' says Joe. "This way the children get to drink good water and when the school is not in session, the entire village gets to use the safe, clean water from the school tank.''

***

The rain-catchment systems set up for schools and villages cost approximately $900, and last for years. The tanks are replenished with disease-free rain water every time it pours. They're simple, low-maintenance and have only one moving part - the faucet. "Initially, it was frustrating to see so much clean rainwater going to waste as we did not have adequate storage facilities," says Joe.

Three years later, the couple, with the help of volunteers, have managed to install 56 rain catchment water tanks in the region. "It was not easy setting up the tanks,'' he says. The schools on the remote peninsula were accessible only by boat which meant equipment and volunteers could not be transported easily. "It was not the installation of water tanks that took much of the time but fixing hot zinc roofs ]since zinc is a non-ferrous metal, it ensures that the water does not get contaminated with rust over a period of time] on the school buildings and the piping for rain-catchment gutters.

Born to serve

There was no easy way to do it. With the hot tropical sun shining bright, it was tough to work. The volunteers worked hard quenching their thirst with coconut water. All that kept them going was their determination," he says.

Hard work in difficult terrain was not something new to Joe. He had done a lot of volunteer work in several parts of Africa. "It was my mother who helped me understand the need of living for others,'' he says. Thanks to her influence, early in life, he was keen to work towards encouraging people to foster a sense of tolerance and selflessness.

After college in Oregon, he volunteered with a charity working in Africa. "My motives, then, were partly to balance the wrongs I had seen as a child, and partly to see the world outside the US," explains Joe.

"I went to Nigeria with the World Care and Concern (WCC) charity in 1954. In Nigeria, I lived and worked in a leprosy colony, helping the people there. The Director of the centre took care of the people as best he could. My work was primarily to boost their morale - to socialise, listen and talk to them so they didn't feel so isolated and alienated. Later, I organised a mobile, boat-based medical clinic that served the river-front villages of the Niger River Delta of Nigeria. I worked in Nigeria for two years until I contracted malaria and was sent back to the US on medical leave. I was incapacitated for four years with a virulent form of malaria and was unable to work."

But Joe did not allow his ill health to douse his spirits. He became a consultant and ad hoc adviser to other charities in the US.

Recounting her life before she went on the journey of saving lives in these remote islands of Panama with her husband Joe, Maribel says, "I was raised in a traditional Spanish home in Costa Rica. Family and friends were the centre of my life. After college and learning English, I went to the US and helped families take care of their children while both parents worked. That is when I saw a very different way of life. People worked so long and hard to get ahead they had little time left for their children and even less for their friends," she says.

"I always thought money would bring happiness, but I found that wasn't so. The experience helped me understand what counts in life are family, friends and closeness. I had all that in Costa Rica when I met Joe, who had retired there. Before I knew it, we had an experience that meant giving up all that closeness to live on a remote, isolated island among people very different from me. It wasn't something I would normally choose to do, but I felt I should follow my husband, share in his work and do what I could to help those who are less fortunate."

"We collect donations from our well-wishers to make money and install water tanks. I donate my monthly Social Security cheque to keep the work going," Joe says. As a couple that receives no compensation, Joe and Maribel look to other volunteers to come and help them. Some groups not only donate money for the tanks but visit them and help install them as well. "Volunteering groups numbering up to 15, stay for as long as a week in a dormitory at our base and help the people by installing rain-catchment tanks, conducting dental clinics and providing reading glasses...'' They have had college students from Quebec, farmers from Iowa and visitors from Europe, North America and Australia.

Change forever

One common refrain Joe and his wife hear during the "departure interviews" is ‘I came to change lives, and changed my own.' But then even for Joe and Maribel, the change was extreme. Joe played golf on manicured courses. Now he spends most of the time in muddy boots, hiking to schools and villages off the beaten track. Starting work at 4am through the week, the couple still strive hard to meet the requirements. "Life where we live is very basic and somewhat primitive."

When Joe went to a city on the mainland after four months in the islands he walked into a cafeteria with a long counter full of well-presented, delicious looking food piled high in trays. "I stood there dumbfounded. Do people live like this?,'' I asked myself, he says. "[Perhaps] four months of rice and beans, alternating with beans and rice will do that to you."

The couple live on an isolated island between two major Guaymi population centres. The canoe route runs between the over-the-water house of Joe and Maribel. Soft calls of "Maribel" are heard day and night from people requesting their help. "Most are calls for first aid. Night time calls usually mean someone has been bitten by a poisonous snake and must be rushed to the nearest hospital on the mainland. The snakes own the night in these islands. The rule is, never put your foot where you don't shine a light," she explains. Maribel's biggest concern is when snakes get into their house. Most are small and poisonous. She does a room by room "snake check" before going to bed each night.

"I'm no saint," says Joe, uncomfortable when people profusely praise his work. "I was lucky to have a father who taught me by examples, not with words and he is the person who inspired me the most," he says. "He was always honest, treated others the way he wanted to be treated and was generous when he couldn't afford to be. He cared for others in a quiet, unassuming way and considered friends to be treasures. And they reciprocated. My goal is to encourage adolescent minds to make a difference and relieve them from the notion that they are incapable of bringing optimistic change."

Highlights of operation safe drinking water

- The commercially-available water tanks are made of plastic and have a capacity of 600 gallons. This capacity is not significant because the tanks are not "storage" tanks, but catchment tanks.

- Each tank costs $900. It is trouble-free, low-tech, with only a single moving part - the faucet -and lasts for years and refills every time downpours happen.

- A tank is refilled in as little as three hours in a tropical downpour, depending on the size of the roof catchment system. Each tank is used by an average of 80 students and 250 villagers.

- The first tank was installed at Bahia Grande School on the island of San Cristobal. Two months later the principal reported a descended rate of absenteeism from sickness, dropping from 75 per cent to 10 per cent.

- Joe and Maribel are now focused on installing 42 rain catchment systems at schools before the school year starts at the end of February. They want the children to start school with safe water.

- A major improvisation the couple did was to connect the safe pipe water from the tanks to the school kitchens.

- Donors of the tanks can install the tank themselves or get it installed by other volunteer groups. The tanks will have the name of the donor person or group inscribed as a memoir.

- -You can donate online via their website http://www.operationsafedrinkingwater.org or get in touch with them via email opsafewater@gmail.com

Do you know of an individual, a group of people, a company or an organisation that is striving to make this world a better place? Every responsible, selfless act, however small or big, makes a difference. Write to Friday and tell us who these people are and what they do. We will bring you their stories in our weekly series, Making A Difference. You can email us at friday@gulfnews.com or to the pages editor at araj@gulfnews.com