Mohammad Doyo seems to have a dream job. Every evening at sunset, he sets off on patrol into the splendour of Kenya’s savannah, glimpsing lions chasing down darting Thomson’s gazelles, hearing the calls of red-chested cuckoos and, when there is a full moon, seeing the majestic, snow-capped peaks of Mount Kenya in the distance.

But Doyo can scarcely stop to admire the extraordinary views because he and a large squad of rangers must protect one of the rarest species on earth, and the star attraction at the 350-square kilometre conservancy: Sudan, the world’s last male northern white rhinoceros.

“This responsibility weighs so heavily on our shoulders,” says Doyo. “It is sad what human greed has done and now we must keep watch every minute because it would be unimaginable if the poachers succeeded in killing these last few animals.”

The precipitous decline in the number of rhinos in the wild is one of the most striking examples of the effect of the rise in poaching in the 20th century.

About half a million rhinos roamed in Africa and Asia at the start of the last century. That figure had fallen to 70,000 by 1970, with some species on the brink of disappearing. By 2011, the western black rhino was declared extinct, a remarkably abrupt end for a species that had walked the earth for five million years.

Recent conservation efforts have rallied overall rhino numbers to 29,000 but poaching remains a real threat.

Some sub-species are under greater threat than others and the northern white rhinos lead the most precarious existence.

An accident of geography meant that these magnificent animals, distinguishable from black rhinos by their square lips and hairy ears, were decimated faster than other sub-species.

Northern white rhinos were found in some of the most unstable countries in Africa, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic and Sudan. A population of about 2,000 in the 1960s had dwindled to only 15 in the DRC’s Garamba national park by 1984 and the last few were soon wiped out by poachers.

Today, there are only five remaining, of whom three are to be found at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy, a windswept ranch of dun-coloured thickets and acacia trees in central Kenya, where efforts to save the species are centred.

All the pressure is on Sudan to try to save the sub-species with Fatu and Najin, the two female rhinos with whom he shares a 300-hectare enclosure. But continuing the lineage may be too much to ask of a 42-year-old male who spent most of his life in a Czech zoo before he was transferred to Kenya in 2009 in the hope that life in the wild might offer a better chance at procreation.

Not that being the saviour of species seems to be a heavy burden for Sudan. A massive presence, weighing in at 1.2 tonnes and coloured a silvery brown with speckles of the dung and mud in which he likes to wallow, Sudan may have noticed that he is a bit special.

Kept under 24-hour armed guard, with a stream of visitors every day, he plays along, rising with great reluctance at the call of his keeper before munching the lucerne grass, or alfalfa, of which he is especially fond and inviting his keeper to rub his back.

Yet Sudan, who is in old age (rhino life expectancy is 40-50 years) embodies the struggle to beat the scourge of poaching, which has driven these animals with few natural predators to the brink of extinction. The Ol Pejeta ranch is also home to 106 black rhinos, making it the biggest rhino conservancy in east Africa.

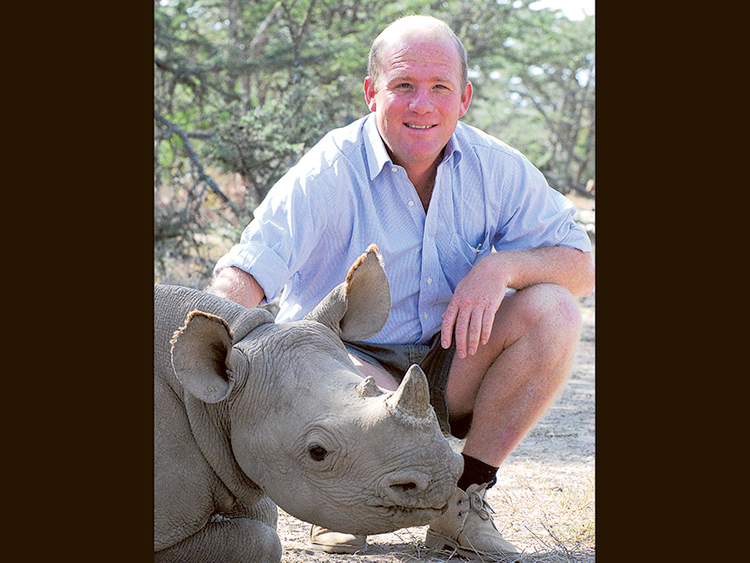

“The pressure from poaching is constant,” says Richard Vigne, a second-generation Kenyan of British origin who is Ol Pejeta’s chief executive. “Securing rhinos has become so expensive and risky that many conservancies have given up keeping rhinos altogether and brought them here.”

The slaughter of rhinos for their horn is fuelled by demand in east Asia, which has risen as countries such as Vietnam and China have become richer.

Rhino horn is made of keratin, the same material as human toenails, but the unfounded belief that it cures everything from hangovers to cancer and can serve as an aphrodisiac has fed demand and sent prices soaring to an estimated $75,000 (Dh275,486) a kilogram.

Vigne says progress has been made in tackling poaching but it is uneven. “In fairness to the Kenyan government, they have done a good job, especially in tightening sanctions for those caught. But it’s not the same everywhere and in places such as southern Tanzania, poaching is simply out of control.”

Even South Africa has seen a stark rise in poaching, losing a staggering 1,215 rhinos in 2014, up from just 13 in 2007.

To win over the support of local communities who often resent the huge tracts of land required to keep animals in their natural habitat, the Ol Pejeta ranch is championing what it calls an integrated land-management model that sees it keep cattle and grow wheat in some areas, which means employment for more locals and income that helps to fund conservation efforts.

A sharp downturn in tourists coming to Kenya has squeezed revenues, prompting the conservancy to launch an online fundraising campaign.

With the clock ticking on Sudan’s life, veterinarians at the zoo are expected in the next few months to find artificial ways of keeping the sub-species alive. They will harvest semen from Sudan and combine it with eggs from a female northern white rhino to create an embryo that will be reimplanted in a southern white rhino to yield a calf that is a pure northern white rhino.

“It is unfortunate that it has come to this but we have to keep looking forward and hope the future is brighter than the past,” says Vigne. “The key task for conservationists is to ensure that there are more births than deaths of rhinos, which is not an easy task but we must take it on.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

The vanishing race

500,000 The estimated number of rhinos that existed across Africa and Asia at the beginning of the 20th century

29,000 The remaining number of rhinos globally. In 2011, one sub-species, the western black rhino, was declared extinct

1,215 Number of rhinos poached in South Africa in 2014 alone. Seven years earlier the number of poached rhinos was just 13