The Dream Shall Never Die: 100 Days that Changed Scotland Forever

By Alex Salmond, William Collins, 272 pages, £12.99

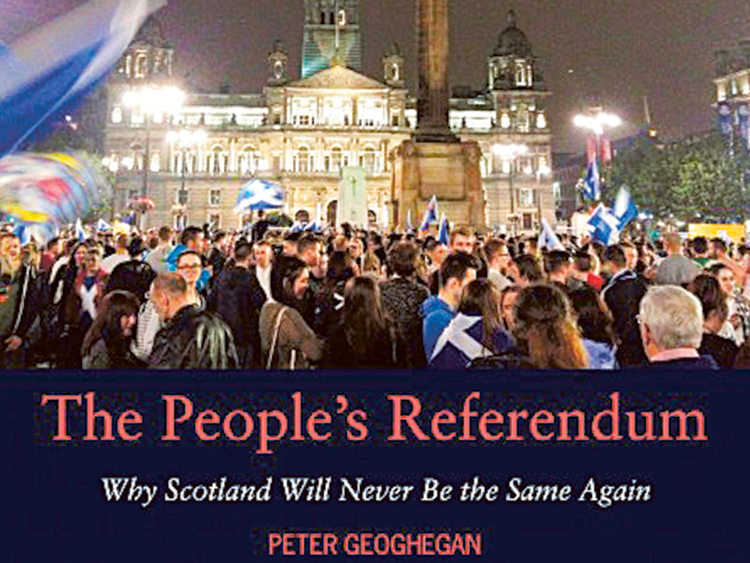

The People’s Referendum: Why Scotland Will Never Be the Same Again

By Peter Geoghegan, Luath Press, 180 pages, £9.99

Disunited Kingdom: How Westminster Won a Referendum but Lost Scotland

By Iain Macwhirter, Cargo Publishing, 172 pages, £8.99

Nicola Sturgeon: A Political Life

By David Torrance, Birlinn, 208 pages, £9.99

Alex Salmond, then Scotland’s first minister, spent part of the final frantic day before last year’s referendum on independence from the United Kingdom putting the “finishing touches” to a monetary authority for what he hoped would be Europe’s newest nation state.

An opinion poll days before had reported a majority of voters in Scotland backing an end to the three-centuries-old political union with England that created Great Britain. The possibility that one of Europe’s leading states would lose a third of its landmass and 8 per cent of its population had sent shockwaves across the continent and beyond.

It was an extraordinary time for the UK. In the end, Salmond’s planned monetary authority — which the former Scottish National party leader reveals in “The Dream Shall Never Die” was to be headed by the economist and Financial Times columnist John Kay — was not required. On September 18, Scotland voted by 55 to 45 per cent to stay in the UK.

Yet that was not the end of the story. Pro-union politicians thought an easy victory in the referendum would kill dreams of independence for a generation at least. Instead, the vote revealed a startling lack of enthusiasm among swaths of the Scottish population for the political idea of Britain.

Glasgow, once the “second city” of the British empire, voted Yes to independence. As Salmond’s campaign diary and a clutch of other books on the referendum and its aftermath make clear, defeat has, if anything, energised Scotland’s nationalists and left the UK’s long-term constitutional future in real doubt.

Salmond’s book should in theory be the best place to start for an understanding of the campaign and its implications. The former first minister is a supremely accomplished politician and was the dominant figure of the campaign. “But The Dream Shall Never Die” does not do justice to Salmond’s status as architect of the greatest challenge to the UK’s constitutional status quo in decades.

Though Salmond announced his resignation the day after the referendum, he is now seeking to become a Westminster MP and his book often feels like campaign literature interspersed with humdrum descriptions of public appearances. On Monday June 16 2014, for example, he tells us he was “greatly impressed by staff and pupils” during a school visit to Orkney — and adds the helpful reminder that the SNP government has built 460 new schools since 2007, compared with 328 being built in the previous eight years.

There are few chinks to be found in the self-confidence that is a hallmark of a politician who has always had, as Scots like to say, a “guid conceit of himself”.

Salmond says he was responsible for any failings in the Yes campaign but offers little explanation of where he thinks it fell short. A stumbling performance in his first televised debate with No campaign leader Alistair Darling is blamed on bad advice from his team. “I allowed myself to be persuaded to act out of character,” he writes.

Though no doubt good politics, the lack of reflection is telling. The SNP campaign rested largely on claims of the economic and fiscal benefits of independence, including upbeat forecasts for North Sea oil revenues. To minimise worries about the costs and risks, it offered a Pollyanna-ish vision of continued close cooperation with the remaining UK on Scottish terms, most notably in asserting there would continue to be a formal currency union.

However, many Yes campaigners thought sharing the pound would leave Scotland little real economic sovereignty. The plan’s reliance on Westminster goodwill also created a tactical vulnerability that the No camp exploited by ruling out currency union.

Kay — the man tasked with steadying the monetary ship in the event of a Yes vote — had himself dismissed Salmond’s threat to walk away from Scotland’s share of the UK debt as “playground bluster” and declared that, while currency union was a rational outcome, it was one “hard to reconcile with the Scots’ pursuit of independence”.

In the end, doubts about the economic case and a feeling that there were unanswered questions were major reasons why Scotland voted No. Salmond blames this in large part on what he sees as unfair reporting by Scottish and UK newspapers and the BBC. The complaint is in part understandable — much of the printed press was hostile and some BBC reporting took a London metropolitan perspective on events in the north. Yet Salmond hardly comes across as a champion of media independence.

His diary records him phoning editors to lambast them for their coverage. At the SNP conference in Glasgow recently he told members they should buy the National, a new daily newspaper so politically committed that it carries a pledge of support for independence on its masthead.

Salmond’s anger at UK government tactics, including the orchestration of big business into a “scaremongering” campaign, also looks one-sided. The Treasury did stretch civil service detachment in its defence of union but Salmond himself used state resources to prepare a “white paper” vision of independence that often read like an SNP manifesto.

The UK deserves considerable credit for treating the push for independence — which many states around the world would instinctively suppress — as an issue to be resolved by Scots themselves through an open and democratic process. Such a response could not be assumed even within Europe, as Peter Geoghegan, a contributor to the National, notes in “The People’s Referendum”. This is a meandering but acutely observed account of the campaign, which includes side-trips to Spain and the former Yugoslavia.

In Catalonia, Geoghegan reports that local nationalists often single out David Cameron rather than Salmond for praise because of the British prime minister’s willingness to let Scotland decide its own fate — an option Spain’s government has firmly ruled out.

Geoghegan is properly sympathetic to the many people in Scotland for whom the referendum posed a fundamental challenge to their sense of British identity, and to others who liked the idea of a sovereign Scottish state but worried about the price-tag. Yet the Irish journalist’s encounters with independence activists illustrates how the Yes campaign became a vehicle for dreams that had appeal far beyond traditional identity nationalism or the SNP’s optimistic economic prospectus.

On a Glasgow street, he finds a literature graduate tending a “wish tree” on which anyone can write their hopes for the future. “I want to effect a change in my lifetime,” she tells him. “I don’t see change coming from within the existing structures.”

In “Disunited Kingdom”, veteran Scottish commentator Iain Macwhirter contrasts the imagination and optimism of the wider Yes movement with a No campaign that focused largely on raising doubts about the case for independence.

Macwhirter started out as a proponent of greater devolution. But he swung to Yes because of lack of English enthusiasm for meaningful constitutional change and a belief that the SNP’s “indy-lite” proposals would ensure a continued high degree of integration between Scotland and the remaining UK.

The final push came from UK chancellor George Osborne’s emphatic dismissal of any Scottish claim to shared used of the pound. “This is not a relationship of equality,” he writes.

Macwhirter now firmly believes that Scotland will eventually become independent. The task of leading the way falls to Salmond’s successor as SNP leader and first minister, Nicola Sturgeon — the subject of journalist David Torrance’s new unauthorised biography. Though as Torrance acknowledges, this is an “interim” work that largely distils existing sources, it offers a timely and valuable perspective on a leader who for much of her career has been little known outside Scotland but who looks likely to have a big impact on the UK’s political and constitutional future.

The picture that emerges is of an impressively disciplined and hard-working politician, a formidable campaigner and capable minister who is less obviously charismatic and more cautious than her mentor and predecessor, but also perhaps more self-aware.

Salmond’s decision to make way quickly for Sturgeon’s election was a masterstroke. The 44-year-old former lawyer from a working-class family is a less divisive figure than her predecessor — and offered at least the impression of a fresh start. Her nationalism is less romantic and more utilitarian.

While Salmond happily finds referendum analogies in Scotland’s bloody medieval wars of independence, Sturgeon sees the case for independence in principles of democracy and social justice, not “nationhood or Scottish identity”.

Torrance finds impressive consistency in Sturgeon’s commitment to causes such as gender equality, helping the disadvantaged and opposition to nuclear weapons. Yet she is not too principled to be effective. She has recently been fending off justified questions about the budget implications of her demand for “full fiscal autonomy” from the UK by accusing opponents of talking Scotland down.

Her claim that only the SNP can truly represent the nation is offensive to proudly patriotic pro-union Scots. And her speech to the recent SNP conference was a carefully crafted effort to destroy Scottish Labour, but one introduced with a noble-sounding call for voters to put “the normal divisions of politics to one side”.

It all appears to be working. Polls suggest that the SNP will win a majority of Scottish seats at the UK parliament in May’s general election, giving it a powerful voice in a hung parliament — and another platform to prepare for another independence push. But Sturgeon cannot expect to have things all her own way. New tax powers for the Scottish parliament over the next few years will make it harder for the SNP to blame all budget pressures on Westminster.

Still, ensuring Scotland remains in the union will surely require a more considered response than the hasty package of new powers promised by pro-union parties during the referendum campaign. It is unclear whether the British establishment is up to the task.

Westminster quickly returned to politics as usual after the referendum. Conservative leaders have even sought to win tactical advantage by suggesting an SNP role in deciding the UK government would be a “threat to democracy” — an argument that can only reinforce nationalist claims of political divergence north and south of the border.

Much will depend on whether England really cares if Scotland stays. The signs are mixed. In 1995, 100,000 Canadians trekked to Montreal to appeal for Québécois to reject independence. A similar effort in London last September attracted only a few thousand people. The passionately pro-union Conservative MP Rory Stewart had to abandon plans to organise a human chain along Hadrian’s Wall (the ancient border, now in northern England), settling instead for establishing a cairn on which opponents of independence could show solidarity by depositing painted stones.

When Geoghegan spent half an hour at the site a few weeks before the vote, there was nobody else there. “The Auld Acquaintances Cairn was meant to symbolise the connection between Scotland and England,” he writes. “As it was, Rory Stewart’s empty field with its hill of stones and half full tins of paint looked doleful, even pathetic.”

–Financial Times