Soon to be joining the likes of Pooh and Paddington is a onesie-wearing streetwise bear, created by illustrator Sav Akyuz and actor-rapper Ben Bailey Smith (aka Doc Brown).

On a damp January morning, I am on my way to meet Smith, otherwise known as rapper Doc Brown, and illustrator Akyuz for a coffee in central London. Their friendship is, as they have admitted themselves, an unlikely one.

As Smith has said: “Who would put together a Jamaican rapper and a Muslim Turk as best mates?”

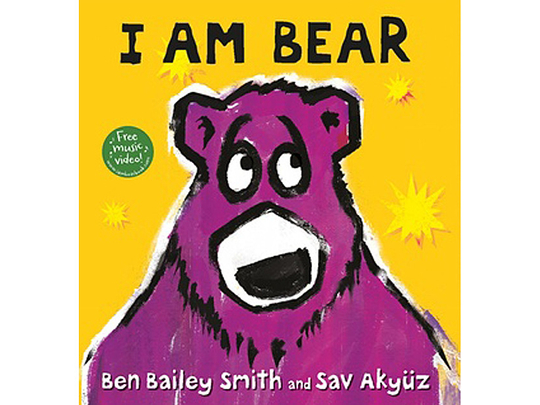

If there is an answer, it has to be: London. Both are children of immigrants and first-generation Londoners. Smith’s mother is Jamaican, his father British (his sister is the novelist Zadie Smith). Akyuz’s family came from a Turkish mountain village where no one read children’s books. And this fact alone makes our reason for meeting as unlikely as the friendship itself: the two are about to publish a tremendous children’s picture book, I Am Bear, secured, after a keen bidding war, by Walker Books.

When parents take away technology, the kid will want the next best form of entertainment — a bedtime story.

Ben Bailey Smith — I have been a fan of Smith’s ever since watching his irresistible, faux-aggressive rap about how to make tea on YouTube, a hilarious brew of lyrics. He has a gift in everything he does for sending up cool but now, when I meet him, my first impression is that he is withheld, in a studied way, in peaked cap and understated clothes — deliberately unflamboyant. It is only when he talks — fluent, funny, forthcoming — that I redraft that first impression.

Akyuz is tall, dark, bespectacled and radiates humour and intelligence. He is straightforwardly present. It is not hard to see why the two like each other. But we are here to salute a third character: Bear, a dude in a purple, furry zip-up onesie who is about to join the great company of bears in children’s literature from Pooh to Baloo to Paddington. Akyuz was working as a storyboard artist on a John Lewis project when he first sketched Bear and spotted “a spark in his eye”.

He thought: “I have to do something with this guy.”

Bear is, rather saucily, bare beneath the suit. He has anxious eyebrows but his rueful look is a foil. He is a prankster and ruthless eater who lunches on squirrel. He has a streetwise gait - in the last picture, he saunters off with a thumbs-up. Inevitably, he is a rapper too - it’s impossible not to see him as Smith’s alter-ego.

Smith and Akyuz explain that it is through football that their friendship was consolidated. Ten years ago, Smith started Sporting Chance FC.

“We were old and battered, trying to play against young whippersnappers.”

Today, they fall over each other conversationally, as, apparently, they have done on the pitch, describing their spectacular own goals. Luckily, these do not feature in their professional lives. Smith relished writing I Am Bear - “It was spontaneous, quick, organic. Every page was like a memory.”

The best picture books, they agree, are the ones you know off by heart (David McKee’s Not Now, Bernard is their favourite). They tested Bear on their children: Akyuz has a four-year-old daughter and a two-year-old son; Smith has daughters of 10 and seven.

I Am Bear aims to encourage parent/child conversation and it did - it went down a treat. Like most parents, they worry about technology taking over.

Smith’s 10-year-old has been refused a smartphone, though her friends are relentlessly on WhatsApp (Smith’s compromise is to lend her his phone for limited stretches).

He maintains: “Good parents do the boring stuff. They’ll do a bedtime routine. When parents take away technology, the kid will want the next best form of entertainment - a bedtime story.”

So books are second best?

“No question. If I was to break up story time and say to my youngest, ‘Do you want to have a quick play on the iPad?’, she is going to say, ‘Hell, yeah.’”

How much has childhood changed and parenting with it?

“My childhood is vivid for me,” Smith says. “I felt like I had it all. It’s crazy looking back and realising we were poor. I had no sense of that. I felt I lived like a king.”

Smith grew up “between Willesden and Kilburn”. His father “earmarked space in newspapers and magazines for advertising, a job that was way beneath a man of his experience and intellect”.

Smith’s parenting style diverges from his father’s in one surprising way: “I was raised an atheist. Aged 10, I wanted to find God, but it didn’t last long. I’ve told my kids they can make their own minds up. And they go to church.”

Akyuz has conducted gentle rebellions, too. He struggles not to force his kids to eat - his mother couldn’t tolerate food left on the plate. He comes from a family in the rag trade.

“My father had a factory in Stoke Newington for CMT (Cut, Make and Trim). My dad is quite a raw guy, but worked his backside off. He had clients like Burberry and Aquascutum. For a guy who didn’t speak much English, had almost no education and was in a new country, he did really well.”

From the age of 10, Akyuz worked in his father’s warehouse in the summer holidays.

“Dad was a strict boss. We kept our heads down. I learned a lot about hard work even though I was this happy-go-lucky kid. Yet, very quickly, I thought, ‘This is not the career for me!’”

Akyuz is the third of three brothers and a sister. He did a foundation year in art and design at Middlesex and studied film at Surrey Institute of Art and Design, the first in his family to work in the arts. His father had hoped he would become the family accountant.

In Smith’s family, Zadie was the first to go to Cambridge and went on to become a literary superstar, scooping up prizes for her novels.

What was she like as an older sister?

“She wasn’t like a sister until we got older. When we were little, we were like twins. There wasn’t much between us in age. We even had a twin buggy and wore OshKosh dungarees - she’d wear a red T-shirt, I’d wear a blue T-shirt. So we were very close and still are. When she started reading a novel a day, aged nine, I thought it a bit weird. I was on Roald Dahl’s Dirty Beasts, she was putting away Little Women in 24 hours. But we all knew she was a prodigy. We bought her a clapped-out typewriter when she was 12 and she tried to write a novel on it immediately.”

He pauses: “The funny thing is, she is still that same girl - very thoughtful, generous and constantly looking out for me...”

Communication within the family matters to them and, Smith and Akyuz agree, clarity was one of their goals with I Am Bear. Smith admits he can “talk for ever” and says he needs an editor. He praises Akyuz for stepping into that role and keeping Bear’s story simple. But you would not want Smith less eloquent. It is this fluency that has contributed to making him a successful actor as well as a rapper.

He volunteers that, as a child, although he would have loved to envisage himself as an actor: “It was not something people from my background did. I know that is a tragic thing to have believed.”

He got his big break on television on the double Bafta-winning CBBC series 4 O’Clock Club, which he wrote and presented. Since then, he has come to feel that acting is mainly about “emotional intelligence”. (He is about to star in the ITV drama Brief Encounters and has just finished filming Life on the Road , with Ricky Gervais.)

His training? Rap battle nights.

“At 12, I was writing raps for girls I fancied... although I’d never show them.”

At 21, one night in Dingwalls, Camden, urged on by his mates, he took his chance.

“If you weren’t from the street, you felt awkward, an outsider. My act has always been based on incongruity and humour.”

Rap was “unreconstructed” in those days: “You’d have a guy in your face, sometimes shoving you around. There were no women, no YouTube, it was street guys who had been dealing with the police, with drug deals that had gone wrong, fights, knives - thousands of young men stuffed into Dingwalls.”

But he got through to the quarter finals and that gave him confidence to rap on. Smith’s comic acts are written with flair but he vigorously denies he shares his sister’s talent.

“We both respect the power of the word. But writing is what I do when nobody wants me to do anything else. It is the biggest luxury. I was round at Ricky Gervais’s house and his equivalent is to paint in his spare time - he is really good.”

Gervais came across Smith on YouTube.

“Ricky phoned me and said, ‘Wazzup, Doc?’ and then did the laugh that was really annoying. I didn’t recognise his voice. And then he said, ‘It’s Ricky Gervais.’ I said, ‘What? Seriously, I’m quite busy so whoever it is, please get on with it.’”

Gervais’s people came on the line and Smith understood it wasn’t a hoax. He remembers thinking: “Whatever this guy asks, I’m going to say yes. I watched The Office like everybody else and he is one of my comedy heroes.”

And then he tells, at amusing length, what it was like being Gervais’s warm-up act on prestige gigs in Oslo and Stockholm. Smith’s comic talent is only half the picture. The serious side is evident too. He is still involved in the asylum seekers charity Salusbury World that he helped start in his 20s as an assistant to Nina Emett (“she deserved an OBE”). The charity was named after a Kilburn street in which there were “horrific B&Bs, purchased by the Home Office for asylum seekers”.

At that time, they were from Kosovo, Somalia and Chad or “wherever there was a crazy civil war going on”. Salusbury Road’s primary school, which had been “nice, happy go lucky, arty farty”, was taking in kids who had “seen their parents die or lose limbs or had gone on some mad journey across the world to be safe. It was a huge problem and Nina took it on”.

Over eight years, supported by the National Lottery and Comic Relief, Emett and Smith built the charity together.

“We went from firefighting for asylum seeking children to working with children who had full refugee status and children living below the poverty line in south Kilburn.”

The charity, necessary as ever, is now run by Sarah Reynolds - “a friend, another amazing woman”.

What’s clear from Smith’s and Akyuz’s stories is that they have dared to be their own people - it is inspiring to meet them. But neither of them likes bossily improving endings.

“With Bear, there was never going to be a big moral,” Smith says.

And what I take away with me is not a moral at all, although it comes across powerfully just the same - it is that you are lucky if you have an older sibling you admire. For Akyuz, his big brother was such an “idol” when he was little that “even just walking to the shops with him, I was massively proud”. It was his brother who encouraged their parents to let Akyuz go his own way in life.

And Smith’s last words are about Zadie: “She made me feel you can do anything.” And this “anything” is certain to include the comeback of the bear in the purple suit.

I Am Bear is published by Walker Books on 4 February.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd