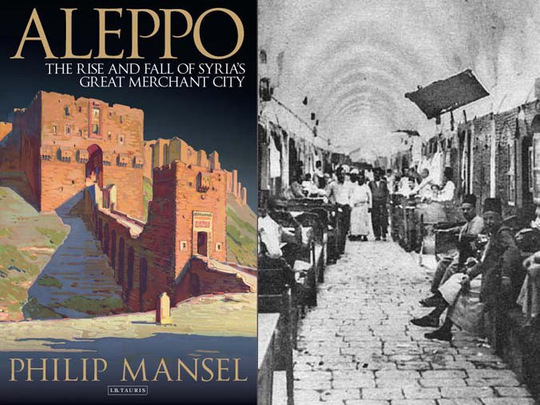

Aleppo: The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Great Merchant City

By Philip Mansel, I.B. Tauris, 224 pages, $28

Aleppo’s glorious centuries as a sophisticated metropolis are under devastating attack as Bashar Al Assad’s government air force rains down destruction on the city and its civilian population. Repeated air raids using barrel bombs on the opposition-controlled eastern part of the city have killed hundreds of people in the past few weeks alone. An air strike that hit a hospital two weeks ago left 27 people dead, including children and doctors.

The vibrant city of more than two million inhabitants before the civil war started in 2011 has been reduced to no more than 500,000, many of whom are suffering under the government siege of the eastern parts and face starvation and death.

What is not obvious in the horrifying news reports of shattered streets and ambulances trying to find their way through the rubble is that today’s people of Aleppo are the direct heirs of the centuries of Syria’s glorious cosmopolitan past. Aleppo was one of the main entrepôts at the western end of the Silk Road, which ran through Iran and central Asia to China, and till very recently the city was a byword for culture and sophistication.

This shattering fall from a golden age has been recorded by Philip Mansel in his fascinating new book, “Aleppo: The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Great Merchant City”. In the first half of the book he brings his deep expertise to play to use a vast range of original sources to tell the history of Aleppo in his own words from the early Ottoman era right up to the tragedy of the civil war. He then uses a longer second section to offer a delightful collection of excerpts and transcripts from the diaries and writings of the astonishing range of travellers and residents who have enjoyed the delights of Aleppo over the centuries.

The key to the success of this book is Mansel’s detailed knowledge of the city and the sources that bring a real flavour of the centuries, going back to the early Ottoman period when a wide variety of nations maintained consulates in the city, and international merchant houses traded goods in one of the Middle East’s largest bazaars with miles of covered streets.

In the 1600s the consuls in the city would have been the first Europeans to hears news of Arabia, the Gulf, Iran, and India, and their dispatches back to Westminster or Versailles through to their ambassadors in Constantinople gave their governments a sense of what was happening across the whole of West Asia. They also enjoyed the privilege of being leading members of Aleppine society and were an integral part of the cosmopolitan mix of the city.

One example Mansel details in his history was the Chevalier d’Arvieux who represented both France and the Netherlands in Aleppo from 1679 to 1686, and left six volumes of memoirs describing his impression of Aleppo as an intricate machine, each piece of which helped the others to function. D’Arvieux had been a merchant in Smyrna (modern Izmir) and Sidon, as well as being the French Consul in Algiers, and he also found time to maintain an official position in the French court as an equerry to the governess of the royal children. In 1668 he sent gazelles, canes and manuscripts to Louis XIV’s minister Colbert. This sophisticated pillar of society spoke Turkish, Armenian, Arabic, Greek and Hebrew as well as a variety of European languages, and Mansel revels in describing his lifestyle in Aleppo.

But D’Arvieux also had to work, and he handled a whole range of problems over customs rates, pilgrims and slaves, and had to sort out the mess when his fellow countrymen were assaulted by marauding bedouin or drunken soldiers. As consul he also acted as a judge on commercial disputes between French merchants as the Ottomans had ceded the right to judge between foreign nationals.

It is important that Mansel’s history does not get stuck in Ottoman nostalgia, and a very useful part of the detailed scholarship which he records with such ease includes how figures from Aleppo were part of the early stirrings of Arab nationalism. Mansel tells how Abdul Rahman Al Kawkabi was born into a prominent Aleppine family and edited the newspaper “Furat” (Euphrates) from 1875 to 1880 but had to move to the freer atmosphere of Egypt to urge the Arabs to embrace modernity and challenge Ottoman tyranny, writing: “If I had an army at my command I would overthrow [the Ottoman Sultan] Abdul Hamid’s domination in twenty-four hours.”

Taking the story up to modern times, Mansel also records one of the seminal moments in the growth of sectarian violence. It was in Aleppo in June 1979 that more than 30 cadets from the Aleppo Artillery School were taken away and murdered by the Fighting Vanguard of the Mujahideen. Most of the dead were from the minority Alawi sect of the ruling Al Assad family, and a year later government forces rounded up 8,000 “suspects” and 25,000 troops and tanks were used to “clear” the city.

Ironically, after Bashar Al Assad succeeded his father as President of Syria in 2000, the city enjoyed a brief renaissance. Al Assad visited it more often, and many historic buildings started to be restored after the Old city was listed as a Unesco World Heritage Site. The city’s economy began to revive and businesses were doing well, which makes it all the more awful when Mansel rounds up his history of the city with a compilation of reports from the violence of the current civil war and ends with the chilling prediction: “The contrast between Aleppo’s past and its current catastrophe is a warning to other cities. Even the most peaceful cities are fragile. States and religions are killing Aleppo. People and monuments are dying. Satellite imagery shows that there are now almost no lights at night in the city. In the twenty-first century, Aleppo has entered its dark ages.”

This frightening shut-down is a very long way from the images the book quotes at length in its second half made up of longer excerpts of travellers’ tales of Aleppo. An American traveller, Bayard Taylor, wrote in 1854 that he was received everywhere with the greatest hospitality in homes of hewn stone with courtyards paved with marble and small beautiful gardens. “The sheer round of visits was a feat of strength, and we were obliged to desist from sheer inability to support more coffee, rosewater pipes and aromatic sweetmeats. The character of society in Aleppo is singular, its very life and essence is etiquette.”

We have to hope that the current violence will end, so that the Aleppines will no longer have to fear barrel bombs and other torments, and that their rosewater pipes can re-emerge as their great city rediscovers a brighter future than looks possible today. Mansel’s “Aleppo” does a great service by reminding us of the humanity of the city amid its greatest ever tragedy.