Despite social activists and filmmakers’ attempts to resuscitate India’s rich art and craft heritage, numerous art forms are dying and artists are living in obscurity.

Devika Gamkhar has now made a film “Saanjhi: Traditional Kalakar” documenting the lives of Saanjhi artists. Tapping into her background in art and films, Gamkhar decided to make the documentary, her first independent venture, which, she says, “flows in the natural relationship of the art in life and the life in art”.

Saanjhi is a traditional stencilled art from Uttar Pradesh’s Braj region (Mathura, Vrindavan and Govardhan), famous as the homeland of Hindu deity Krishna. People often observed artists making designs in the temples during the festivals at dusk (Saanjhi is derived from the Hindi word saanjh, meaning dusk) and listened to the colourful tales of Krishna.

The art flourished in the 16th and 17th century and temple walls and floors were decorated with Saanjhi motifs.

Originally, the stencils (hand-cut designs) were used to tell stories from Hindu mythology, particularly focusing on the life of Krishna. But later striding latticework pattern of Mogul origin and also contemporary themes were introduced to give it a wider perspective. And then, over the years, the art reached homes and offices.

Sadly, today, Saanjhi has become rare and few artists practise it.

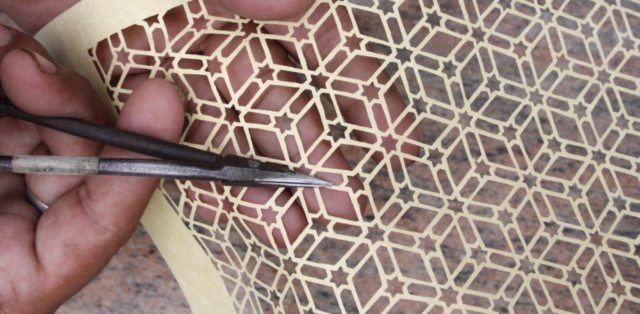

The cutting process requires a lot of skill, concentration and patience and the final detail is achieved with specially designed scissors. The stencils are made on paper and colours are sifted on to the surface. Most popular is the filling of dry colours and meticulous lifting. Since the process of lifting is as critical as the cutting of the design, it has to be done with precision.

Gamkhar’s film, which focuses on one family, provides a glimpse of these steps with the hope that the artists are treated with dignity by the urban folk.

“The purpose of making an intimate documentary with one family, comprising three brothers — Vijay, Ajay and Mohan — was to show the difficulties they face in marketing this ancient art not only in their hometown, Mathura, but also in urban areas, including Delhi,” she says.

The 74-minute film, in a mix of Hindi and English, highlights how creative people, with aspirations and responsibilities in craft, as well as their families, struggle to survive, yet continue to further the cause of art. And their accomplishments are a testament to their immense perseverance.

On being asked how she zeroed in on the Saanjhi art form, Gamkhar says, “I started with Saanjhi because over time, the artists had become known to me. One of the artists, Mohan, had made a Saanjhi paper-cutting of a temple for my parents’ office; hence our association and connection grew over the years. And because it is a self-funded film, the feasibility and logistics of it were more manageable.

“The film was a long time coming. As a child when I would go to the crafts museum in Delhi with my mother, I always wanted to be on the other side of the stone bench — the side where the artists sat and did their work. However, there was no place where one could go and learn the traditional arts, which actually is our fine art.

“I continued to feel the accumulation of this deep loss. And in fact, such inaccessibility to these artists, who ought to be our gurus (teachers), is a big drawback for the nation. So, eventually, I went seeking what I always felt close to — the intangibles of art making. And it was a unique experience.”

As she was making the film, several aspects came to light, which until then Gamkhar was herself unaware of. What continued to trouble her was the obvious blind eye towards traditional arts.

“There are some ‘summer school workshops’ that open from time to time, but it is surprising that we have not been able to tap into the resources of India’s art wealth,” she says. “Even today, students in general and art students in particular are missing out on skills that can only be learnt from the masters of the art. That’s why we remain unaware of both their oral and technical aspects.”

Has her film helped in promoting this art? “Fortunately, Saanjhi is not a dying art,” Gamkhar says. “Like other visual arts, including Madhubani, Warli and Inlay, Saanjhi has evolved in terms of both products and the paper-cutting in keeping with today’s concepts. And my aim will be to bring the artists and those who love the art closer to each other by creating ‘cultural documents’.

But that needs to be done soon. For, finding Saanjhi artists is already a difficult proposition, as many artists have begun getting into other jobs for survival and have even moved out of Braj region.”

For instance: Ram Soni moved out of Mathura 12 years ago and now resides in Alwar, Rajasthan. He has diversified into making lampshades, screens and other decorative items, while continuing to be involved in Saanjhi art and designs for the love of it.

Winner of the National Award, which was presented to him by A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, then president of India, in 2005, Soni is the custodian of this ancient art form that his family has practised for more than 350 years covering six generations.

Soni has been creating Saanjhi works since childhood. “As a child, I was not allowed to do the real work and would only watch from a distance and work on it,” he says. “Since it has been in the family, we have learnt the basics merely by observing. But the real feel comes only by practice, and for a very long time I was not permitted to go anywhere near the scissors.

“When at all my father handed over the scissors to me, he would soon be annoyed and admonish me for not knowing how to do a neat job. He didn’t give a thought to how I would learn if I was not given the opportunity.”

But that was then. Soni is now not only a pro at it,he even allows his daughter to fiddle around with paper, pencil and scissors and do the artwork. One thing, though, is clear: now, children in his family have to get a proper education and take up Saanjhi as a hobby.

However, he admits that even after more than three decades of Saanjhi, he cannot match his predecessor’s standards. “We can only claim of achieving a tiny bit of what artists in earlier times crafted and cut,” he says.

Traditionally only men have taken to this art. Soni explains: “That’s because the method is very detailed and takes about 10 to 12 hours a day at a stretch to work on. A person’s mind and heart has to be in it while the work is on. And with numerous household matters to tend to, it is not feasible for women to work on it.”

Soni shows some of his works, removing each design from plastic folders. There is a huge variety — lovely motifs, peacocks, bullock carts, horses, cows, butterflies and trees – and the designs look gorgeous on coloured paper. With the changing times, he has begun creating artworks in recycled and handmade paper.

He displays his expertise by cutting a design with his sharp, customised pair of scissors, which he manoeuvres for a fraction of a second and creates a stunning border in rectangular form.

Such creations find recognition globally. “My works are appreciated by many foreigners as well as Indians, many of whom display huge artworks in their offices and homes,” Soni says.

His designs have found buyers in London, Germany, Korea and other countries. But one of his proudest moments was when one of Soni’s Saanjhi artwork was mounted at Delhi’s INA metro station. The massive mural comprising a huge tree with small designs around it, all intricately cut, is part of the ‘Crafts of India Galleries’, spaces created at metro stations to give an opportunity for artists to showcase their works.

Among the commuters that metro stations draw in large numbers every day, are youngsters, who are often seen wondering about the depth and richness of traditional Indian crafts.

But sadly, many a time, middlemen and NGOs working in the crafts sector, dupe the artists. “They approach us to show our works to the buyers, but on bagging an order, they pass the order on to others who are not so well versed in the art and are willing to work for less,” Soni says. “I have been fooled by NGOs, who get us to sign on papers written in English but later hand over a tiny amount to us after pocketing the rest of the money. Since I do not understand English, there is nothing I can do.”

Nilima Pathak is a journalist based in New Delhi.