“1497”, a group show curated by Dubai-based Chinese artist Lantian Xie, sets up an interesting dialogue between various artists about the idea of home, belonging and “unbelonging”. As an expatriate who grew up in the Middle East, Xie has an interest in the theme of belonging and gulfs. He has brought together works by artists from different histories and geographies who share the same sentiments, offering various perspectives on the idea of home and what it means to have a home, or to long for one.

The numerical title of the show hints at temporary, permanent or forcibly occupied residences. “‘1497’ refers to three different inflections of homeliness. It could be the number of a room in a hotel or the address of a house. It is also the year in history when Europeans first arrived by sea into the Gulf region and in North America as colonisers. The artworks in this show include images, aromas, texts and objects that allude to a home in which history has taken place, addressing ideas about who a home belongs to, who it is intended for, who is the outsider, and the people and power that goes into the making of a home,” Xie says.

For Xie, the starting point of this show was a painting titled “The Burning” by American master Jacob Lawrence, who is known for his epic narratives of African-American history. It depicts a historical incident during the Haitian revolution, when the residents of a village chose to set their homes on fire rather than to surrender to the advancing French army. “This painting of burning homes represents resistance, and the idea of belonging and ‘unbelonging’. I have installed this painting on the floor because I want to treat it as an historical object waiting to be put in its proper place,” Xie says.

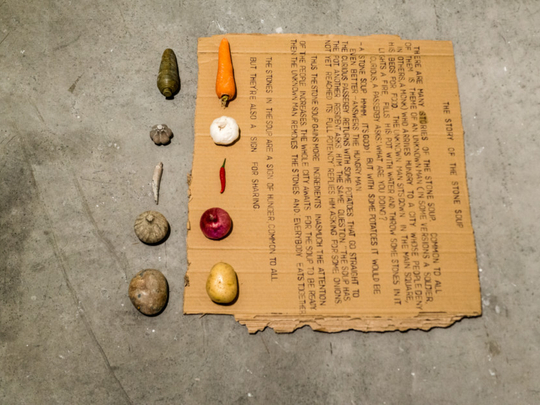

Brazilian artist Matheus Rocha Pitta’s piece “Stone Soup” presents a different narrative. The work comprises vegetables — some real and some carved from stone, and a story. The story is about a soldier who returns from war to find that the people and homeland he fought to defend did not care that he was hungry and destitute. But he cleverly gets the villagers involved in making enough soup to feed not only him but the entire community. The simple but profound work raises questions about the labour and services that go into making and maintaining a house, and about who performs the labour and who reaps the rewards of that labour.

Underlining the heaviness of emptiness and absence pervading this show is a life-size balcony placed on the floor in the centre of the gallery. This work by Turkish artist Hera Büyüktaşçıyan is a replica of a balcony that exists in Istanbul. An anchor rope tied to the balcony is cut at the other end, suggesting the idea of a home being adrift. As a person of Greek-Armenian origin based in Turkey, Büyüktaşçıyan is interested in exploring issues of belonging, loss, identity, memory, space and time. Balconies are a recurring motif in her work as a representation of the boundary between private and public space in a home, and a threshold space that delineates the powerful ones standing on it from the “others” positioned below it.

“This work is inspired by the story of an elderly Greek woman, who was among the thousands of non-Muslim, Greek-origin residents of Turkey that were forcibly repatriated to Greece. She told me that she often returns just to look at her childhood home, which was confiscated by the government. She stands on the street, looking at the balcony above and tries to relive her memories of what she saw from the balcony as a child. That is why I have made the railings of my balcony higher so that when viewers stand on it, they get a child’s viewpoint,” the artist says.

Contrasting with the heaviness of the balcony, and conversing with it is Ubik’s installation “Support System”, comprising three found hooks at different levels of being precariously balanced on a thread suspended overhead. Indian artist Ubik grew up in the UAE, and his contemplation on belonging and seeking security resonates with Büyüktaşçıyan’s work.

The idea of boundary making and the materiality of thread are both present in Indian artist Shilpa Gupta’s series of tree drawings. Each drawing features a tree that grows at and across the borders of contested lands. The trees are created with white thread on white paper, and the lengths of the threads are proportionate to the fences constructed along those borders. The works refers to the politics of home-making by marking your space and excluding outsiders.

Trees also appear as a subtle presence in Dubai-based Saudi artist Raja’a Khalid’s work, “Useful Tropical Plants”. The artist has used a special device to analyse and recreate the chemical composition of the atmosphere inside a greenhouse in Berlin called the “greenhouse of useful tropical plants”. This was established by Kaiser Wilhelm to house and display plants from the lands he had conquered. Visitors with a keen sense of smell will discern the top note of dirt and grass along with the scent of Eucalyptus and other trees released by the diffuser.

The second part of this work is an archival image of an American model, actress and socialite from the 1950s. The picture taken for the cover of “Vogue” magazine has been shot on the beach of a resort in Jamaica, owned by the actress. “She opened the first resort hotel in Jamaica, pioneering the growth of the resort industry around the world. This work speaks about the idea of constructing an ideal place that could be owned, but is in fact entirely a fabrication; it also talks about the people outside the frame and the harshness that goes into the making of these idealised scenarios. There is also the element of imitating a homely environment,” Xie says.

Danish-Vietnamese artist Danh Vo’s work is a copy of a letter made by the artist’s father of a letter written in 1861 by a French missionary in Vietnam to his own father. Written on the eve of the missionary’s execution by the Vietnamese, the letter speaks about his love for his father and his country, and his conviction that both France and he had done nothing wrong in Vietnam. “Since Vo’s father later emigrated to Europe, the work echoes the movement of bodies in and out of Vietnam, pointing to changing, porous borders and dismantling the idea of the fixedness of national affiliation,” Xie says.

The show also includes two commissioned texts by writers Gitanjali Dang and Deepak Unnikrishnan. Mumbai-based Dang’s “Burial at Sea” is about shared intimacies in private spaces inside and outside the home. Unnikrishnan, an Indian who was born and raised in Abu Dhabi, recounts his family’s experiences of living in Abu Dhabi in the 1980s through drawings and diaristic entries. His text, “I come to your country, name me”, highlights the emotional challenges of living in a home that is away from home.

Jyoti Kalsi is an arts-enthusiast based in Dubai.

“1497” will run at Green Art Gallery, Al Quoz, until March 6.