The price of oil is not the only ‘greaser' for expansion of Islamic finance. Lately, a number of countries seem to be pre-empting a social-movement-cum-change of regime as today's ‘oil price' facilitator for welcoming Islamic finance.

But what happens to Islamic finance when alternative energy, solar, biomass, wind, ocean, etc, becomes a viable replacement for oil, or what if the oil runs dry, or the so-called Arab street democracy reaches the Muslim Opec countries, or the anti-Sharia movements in some western countries find another boogeyman?

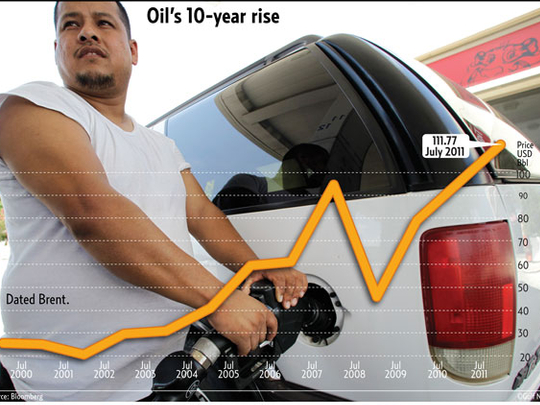

Sukuk rose and became a global phenomenon on the back of petro-liquidity spike and accommodating government environment in GCC countries. The chart shows the price of oil from December 2000 to July, 2011.

It must be noted that the majority of Islamic financial institutions, banks, takaful, leasing, etc, were born between 2003 and 2008 and partly financed the eighth wonder of the world, the Palm Jumeriah.

Inward commitment

The Malaysian Islamic finance story can be considered part of the inward commitment to address the Muslim population, and to attract the GCC oil surplus investments, as well as a springboard into the ten Asean countries and China.

What is the common theme running in China, Thailand, Oman, Egypt, and other places where a restive Muslim population may be demanding Islamic finance without articulating it?

It can be hypothesised that the first Islamic bank to address local popular unrest for Islamic finance in a country was the Philippines. The Al Amanah Islamic Bank was established in 1973, shortly before the formation of Dubai Islamic Bank.

The arrival of Islamic finance in China may well be linked to the political unrest within the Uighur Muslim community in 2009.

For example, the Bank of Ningxia, China's first Islamic friendly bank, attracted global media attention when it launched, but now has called a time out, or a "breathing period of up to 18 months to allow the project to bed down".

The lesson for the Islamic finance industry outside China is that there's a need to follow through with investments, financing, infrastructure or trade finance, to sustain the momentum in large markets like China.

The arrival of Islamic banking in Thailand, the "land of a thousand smiles", is to address the needs of the southern Thai-Muslims, who have been exposed to and influenced by the growing success of Islamic finance in Malaysia.

Islam is the second-largest religion in this multi-religious country, and the faithful want to be financially devout, hence, Islamic Bank of Thailand was formally established in 2003.

The Tunisian fruit vendor, Mohammad Bu Azizi, who had unknowingly triggered the Arab revolution, also paved the way for change in the financial systems of Egypt, Oman, and other Muslim countries where finance has yet to evolve.

The years of lobbying for the Islamic finance industry to gain greater recognition from the government in the largest populated country in the Middle East (Egypt) and in the only GCC country without Islamic finance (Oman) proved to be ineffective. In the "new" Egypt, we are hearing increasing calls for Islamic finance, but not from the Muslim brotherhood. These calls come from the opposition parties seeking the Islamic-friendly vote that appears to be demanding Islamic finance.

Opportunity

In Oman, the Central Bank there stated that it would allow conventional banks to open Islamic windows and license for the first full Islamic financial institution, Bank Nizwa. The irony of the situation is that the Central Bank of Qatar issued a circular earlier in the year for conventional banks to close their Islamic windows, issues of "leakage", by the end of the year and the Central Bank of Oman is now encouraging Islamic windows.

Additionally, there have been Islamic banks recently established in Bosnia, Gambia, Kenya, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, and so on.

For Islamic finance to be a legitimate and credible option for all capital market stakeholders in the post oil and revolution period, let's take the eventual future back to the present. Now, we need to tackle the issues associated with inefficiencies, marketing, and branding associated with Islamic finance.

Let's start with the questions on the mind of western/conventional financial institutions and governments. What is their number one issue for the acceptance and participation of Islamic finance? Is it harmonisation, lack of enough scholars and qualified people, risk management, short-term liquidity, or Islamic equity capital market?

If one looks at major Islamic finance events where there are presentations from regulators, from securities commission to central bankers, like the recent mega event in Singapore, the common denominator is the need for harmonsation in Islamic finance.

Coordination

Harmonisation implies close levels of coordination of Islamic finance stakeholders between and among countries and regions, and it establishes the path to the much sought-after standardisation. But this will only happen over time as structures, contracts and screening become commonplace.

Finally, one country cannot expect to carry the mantle of Islamic finance forward. There must be coordinated and cooperative efforts. So, let's leave our egos at the door and work together for foundational Islamic finance based on merits, as Fortune 500 companies are always looking for financing options and investors are looking alpha strategies (Islamic screening).

The writer is head of Islamic Finance at Thomson Reuters. Opinions expressed are in his personal capacity.