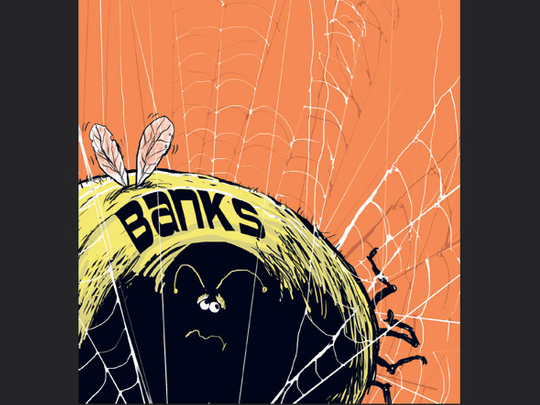

For all the hand-wringing over too-big-to-fail banks, there is at least one simple solution: Shrink them. A more vexing question is how to deal with links between firms and markets that can pose even bigger threats.

While "too big" can be defined by, say, assets or deposits, it is hard, if not impossible, to spot connections that will spawn financial havoc. The government didn't expect Lehman Brothers Holdings's collapse to cause a run on money market funds, and no one foresaw that American International Group could endanger the likes of Goldman Sachs Group or Societe Generale due to credit default swaps.

That is why legislation introduced in the Senate earlier this month to create an agency to map ties among firms while also assessing threats is a good first step toward dealing with too-tangled-to-fail banks. The plan becomes even more important given a possible agreement between senators and the Obama administration to create a council of regulators to oversee the financial system, as the New York Times reported on Wednesday.

That council — likely to include regulators such as the Federal Reserve, Federal Deposit Insurance Corp, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and the Treasury Department — will need unbiased, wide-ranging data and analysis that goes well beyond what regulators have today. This is why legislation to create a data-gathering agency — introduced by Rhode Island Democratic Senator Jack Reed — would prove vital in making any new regulatory set-up work.

Inadequate data

Although regulators now get all sorts of data from financial firms, it's not in a form that can be easily shared. Nor does it, in most cases, dig down to the level of individual loans and transactions. Data also isn't standardised. So regulators can't quickly pull together information from across Wall Street to, say, assess who would get hit if a particular company, financial product or market blew up.

Firms' interconnectedness, and our lack of knowledge about it, was repeatedly raised as a deep-seated danger during a Senate Banking Committee hearing earlier this month. "It isn't the balance sheet of the bank that's a problem," testified former Citigroup Chief Executive John Reed. "It's the interconnectedness of one financial institution with virtually all other financial institutions."

After all, hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management, which blew up in 1998, required a bailout overseen by the Fed not because of its size, but because its trades linked it to almost every firm on Wall Street. The huge growth in financial derivatives, especially credit-default swaps and interest-rate swaps, has only made this issue more acute.

Reed's bill wouldn't look to end connections among firms. It would instead try to map them by giving the new agency the power to require standardisation of transaction data, which financial firms would then have to turn over to the new agency. This would help the firms and regulators get a better picture of who may lose if someone goes under.

Then the plan is that the new agency would analyse the data it collects to map markets and identify potential hot spots.

The proposal is the brainchild of a group of academics, economists and regulators who formed a volunteer committee to push what they dubbed the National Institute of Finance.

Ideally, such an agency would gather quants, numbers geeks, data hounds and just plain old, outside-the-box thinkers who, instead of creating the kind of financial models that lead to bubbles, would spot disaster before it strikes.

Two of the main backers of such an institute — John Liechty, an associate professor of business at Penn State University, and Allan Mendelowitz, a former director of the Federal Housing Finance Board — have compared it to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which houses agencies such as the National Weather Service.

"Our financial markets are at least as important and as complicated as the weather," Liechty testified last week before a Senate Banking subcommittee hearing on such an agency. "If that's the case, why don't we have the equivalent of NOAA for the financial markets?"

Independence

Any new agency will only work, though, if it is independent. That is why it needs to be housed outside existing regulators which have their own biases and often-times parochial views.

As Liechty testified, "You need to have somebody who has the ability to speak the truth in the middle of a crisis or in the buildup to a crisis."

Independence is one potential short-coming of Reed's bill, though. While it calls for the agency's director to serve a 15-year term, it also creates a board that includes the Treasury Secretary and heads of regulatory agencies. That opens the door to political interference.

There will also be complaints about costs. Yet by mandating standardised data terms, such an agency may help banks and other financial firms cut back-office and information-technology costs.

Of course, even if the new agency works perfectly, there's no guarantee it would prevent future crises. For starters, regulators have to be willing to act on warnings. It's also dangerous to put much faith in the ability of complex financial models to predict risk.

Plus, secretive regulators, like the Fed, will likely push to keep much of the information generated under wraps.

If investors, along with regulators, have a better grip on the connections between firms, they will be better able to price risks, or steer clear of them altogether.

That is the real goal. Because ultimately we can't eliminate linkages among firms that form the basis of markets. We can, though, try to manage them.