Here we go again. Every few years, investors get all enthusiastic about Japan. This time the recovery is for real, they argue. This time real change is afoot. This time buy yen-denominated assets and don't look back, they conclude.

The end result tends to be disappointment. This latest episode of euphoria is likely to be more of the same.

It brings to mind Charles Schulz's ‘Peanuts' cartoon: Charlie Brown, Lucy and the football. Time and time again, Lucy convinces Charlie Brown she'll hold the ball for him to kick only to yank it away at the last second. Every time, he lands flat on his back, pondering his gullibility.

Bullishness on Japan often seems that way. Investors notice business sentiment perking up and unemployment stabilising and decide — wrongly — that the great rally we've been waiting for since 1989 is on. This pattern may be playing out yet again.

It's hardly surprising things feel better. Violent drops in growth tend to be followed by sharp upswings. A multitude of variables, including inventory adjustments, policy measures and what economists call "favourable base effects" explain this. When industrial production collapses by almost 40 per cent from peak-to-trough, says Maya Bhandari of Lombard Street Research in London, the snapback will be big.

"Looking through these gyrations is vital," she says.

Worsening deflation

Investors are cheered that firms including Toshiba are boosting investment — and they are buying Japanese stocks. Deflation is far more important, though. As we've seen this last decade, sliding prices are a growth killer. They leave executives stingy with wages and drive households to save, rather than consume. The result is a slow ratcheting down of living standards over time.

The real problem is that officials see deflation as the cause of the problems, not a manifestation. You can see that in how quickly Finance Minister Naoto Kan turned on the Bank of Japan, complaining that its 0.1 per cent overnight lending rate is too high.

If only Kan understood price declines are less about the supply of yen than weak demand. Wages slid for a 21st month in February, extending their longest losing streak in seven years. As long as workers aren't reaping the benefits of export-led growth, consumer prices will fall.

The fact that Kan's Democratic Party of Japan is missing that point gets us to the second reason this recovery will fizzle.

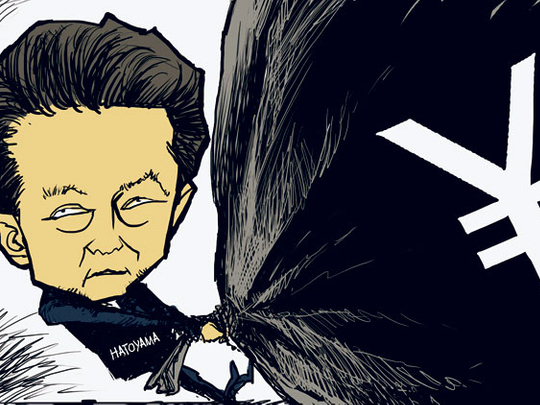

An historic election in August thrust Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama into power. It ended 54 years of virtually uninterrupted rule by the Liberal Democratic Party and promised a new era of enlightened policymaking. Eight months later, he is merely another unpopular and distracted Japanese leader.

Not unlike President Barack Obama in the US, Hatoyama was elected to govern differently — to shake up the status quo and take on a ruling elite more interested in their party than their nation's people.

Instead, he has been neutered by finance scandals. Plans to trim wasteful public works spending and shift government spending away from corporations to households are taking a backseat to political bickering. The buzz has turned to how much longer Hatoyama will be around.

The rise of China, India and South Korea means the world won't wait for Japan to rethink its rickety model. Japan needs to be 100 per cent focused on raising its competitiveness, strengthening its social safety net, increasing productivity, preparing for an ageing population, boosting the birth rate and allowing more immigration.

Need for confidence

Japan is not about to crash; some $15 trillion (Dh55 trillion) of household savings will cushion any fall. Yet tackling these challenges is vital to instilling confidence.

If you want Japan's aggressive savers to spend more, convince them things will be better over the next 10 years than the last 10. Watching Japan Airlines go bankrupt, Toyota Motor crash, Sony eat Apple's dust and China gaining on Japan hardly helps. Nor does talk of a Japanese debt crisis.

Hatoyama's economic team is focused elsewhere. Kan, the second finance minister in six months, is leaning on the central bank to pump more yen into the economy. The truth is, Japan must find an exit strategy from the 1990s. It hasn't learned how to live without zero interest rates and the world's biggest public debt.

All this neglect gets us back to Lucy, Charlie Brown and the football. Now that the Nikkei 225 Stock Average is above 11,000 and approaching the levels at which it was trading before the collapse of Lehman Brother Holdings in September 2008, Japan's challenges are getting short shrift.

Sure, growth will benefit from improving global conditions and that dynamic could boost the Nikkei a bit. That's not enough for Japan. It's been putting off major upgrades for so long that policymakers don't know where to begin. It means Japan will continue to underperform.

For you would-be Charlie Browns thinking it's safe to take another kick at Japan's football, be warned: Lucy may be waiting to spirit it away yet again.