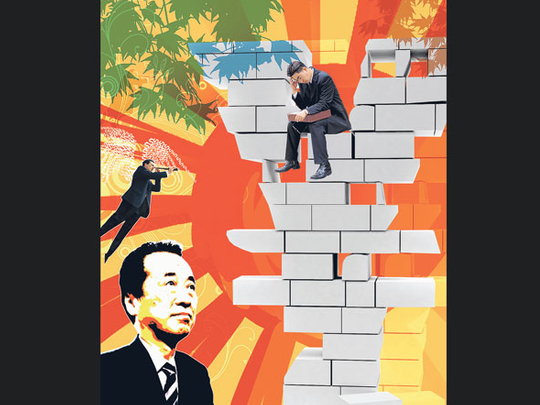

Hirohisa Fujii, 77, always personified Japan's shrinking-population problem. That he was tapped at all to be finance minister underscores the dearth of energetic leadership needed to enliven an economy that has underperformed for 20 years. And now, his untimely resignation reminds us why Japan's funk will live on. A third "lost decade," anyone?

Let's not cast too much blame Fujii's way; his health is slipping. The fact remains, though, that Japan lacks a deep bench of policymakers to tackle deflation. Last week, Naoto Kan became Japan's sixth finance minister in 18 months. Having little fiscal-policy experience, the best we can say is that Kan's age has a six-handle on it — he's 63.

It's not ageist to point out the disconnect between Japan's August election and the economic team that Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama chose. The contest marked a generational shift in which aggrieved younger voters ended the Liberal Democratic Party's half-century rule. The average age of the new Democratic Party government was 48, compared with 55 for the previous one.

Hatoyama's first team to run the $4.9 trillion (Dh17.98 trillion) economy — Fujii and Financial Services Minister Shizuka Kamei, who was 72 at the time of his appointment — boasted an average age of 74.5. Yet it's less about age than their experience.

In the US, for example, I would have much preferred former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, 82, to Timothy Geithner, 48, as Treasury secretary. Fujii and Kamei defected to the Democratic Party of Japan after decades with the tired party it defeated. If that's "change," perhaps officials in Tokyo should consult a dictionary.

Nikkei anniversary

The two-decades-of-negligible-growth yardstick is useful. Last month marked the 20th anniversary of the Nikkei 225 Stock Average's climb to 38,915 points. Today it stands at less than a third of its record high, and gross domestic product, unadjusted for prices, is at its lowest level since 1991. As deflation intensifies, Japan lacks conventional tools to stop it.

The most important tool missing is fresh thinking. Kan might represent just that. His stature rose as health minister in the 1990s, when he exposed that agency's role in allowing as many as 5,000 Japanese to contract HIV through contaminated blood products. He is a champion of wrestling power away from bureaucrats, something that is vital for Japan's outlook.

The odds don't favour Kan being an economic maverick. He isn't the deficit hawk that Fujii was, and economists in Tokyo are abuzz about a return of the public-works policies that created the largest government debt in the industrialised world.

This year, meanwhile, marks the 20th anniversary of the bursting of Japan's economic bubble. To this day, many blame then Bank of Japan Governor Yasushi Mieno for raising interest rates too much. The real cause of the bust was unsustainable asset prices in stocks and real estate and a misguided belief that Japan's boom was unstoppable.

Japan is poised this year to lose its title as second-largest economy, with China projected to slot behind the US. The psychological blow that will have on Japanese politicians and consumers isn't getting the attention it deserves.

Nor does Japan's revolving-door economic leadership inspire confidence. It barely makes sense for peers at Group of Seven or Group of 20 meetings to learn the name of Japan's latest finance minister. Why bother when he won't be around very long?

Few countries in Asia care more than Japan about how the rest of the world views itself. And yet little thought seems to go into how the ever-changing roster of leaders plays out abroad. That discontinuity also comes with a price domestically. By the time a new economic head gets up to speed and staffers adjust, he's gone.

Revolving-door politics make Japan's biggest challenges even more insurmountable. They include reducing debt, shoring up the national pension system, raising productivity, increasing the birthrate so Japan has future income earners to support an ageing population and competing with the Chinese and Indian juggernauts.

Any of these tasks are Herculean in the best of times given how task-oriented Japan's bureaucrats tend to be. GDP is weak in Hokkaido? Build a couple of huge dams. Unemployment is rising in Osaka? A few new highways will help. Okinawans are feeling left out? Here's a nice big bridge project to keep the peace.

Antiquated model

What they aren't good at is jettisoning an antiquated economic model. The government can issue all the fresh debt it wishes, yet it's a short-term fix that distracts from where Japan wants to be in ten years. Households know it and this lack of confidence in the future explains why they aren't spending.

The lack of market reaction over Fujii's resignation is a cautionary tale. Investors shrugged it off because they are used to such departures. There also seems to be a tuning-Japan-out dynamic at play here.

Japan's economy is anything but irrelevant. It is home to Asia's biggest stock and bond markets and has the region's most international currency. Size still doesn't guarantee that investors will remain active in an economy that is taking 20 years and counting to right itself.