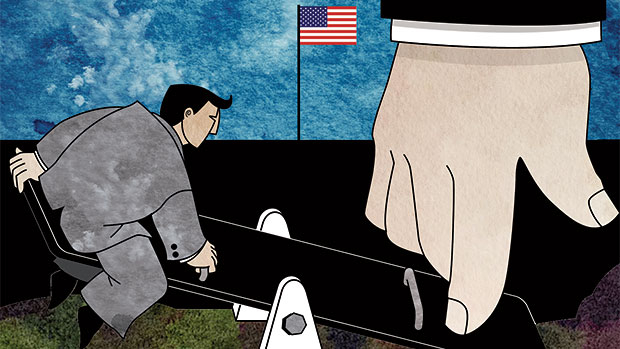

When should growing inequality concern us? This is a moral and political question. It is also an economic one.

It is increasingly recognised that, beyond a certain point, inequality will be a source of significant economic ills.

The US — both the most important high-income economy and much the most unequal — is providing a test bed for the economic impact of inequality. The results are worrying.

This realisation has now spread to institutions that would not normally be accused of socialism. A report written by the chief US economist of Standard & Poor’s, and another from Morgan Stanley, agree that inequality is not only rising but having damaging effects on the US economy.

According to the Federal Reserve, the upper 3 per cent of the income distribution received 30.5 per cent of total incomes in 2013. The next 7 per cent received just 16.8 per cent. This left barely over half of total incomes to the remaining 90 per cent.

The upper 3 per cent was also the only group to have enjoyed a rising share in incomes since the early 1990s. Since 2010, median family incomes fell, while the mean rose.

Inequality keeps rising. The Morgan Stanley study lists among causes of the rise in inequality: the growing proportion of poorly paid and insecure low-skilled jobs; the rising wage premium for educated people; and the fact that tax and spending policies are less redistributive than they used to be a few decades ago.

Thus, in 2012, says the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the US ranked highest among the high-income countries in the share of relatively low-paying jobs. Moreover, the bottom quintile of the income distribution received only 36 per cent of federal transfer payments in 2010, down from 54 per cent in 1979.

Regressive payroll taxes, which cost the poor proportionally more than the rich, are projected to raise 32 per cent of federal revenue in fiscal year 2015, against 46 per cent for federal income tax, the burden of which falls more on higher earners.

Also important are huge increases in the relative pay of executives, together with the shift in incomes from labour to capital. The Federal Reserve’s policies have also benefited the relatively well off; it is trying to raise the prices of assets which are overwhelmingly owned by the rich.

These reports bring out two economic consequences of rising inequality: weak demand and lagging progress in raising educational levels.

The argument on demand is that, up to the time of the crisis, many of those who were not enjoying rising real incomes borrowed instead. Rising house prices made this possible. By late 2007, debt peaked at 135 per cent of disposable incomes.

Then came the crash. Left with huge debts and unable to borrow more, people on low incomes have been forced to spend less. Withdrawal of mortgage equity, financed by borrowing, has collapsed. The result has been an exceptionally weak recovery of consumption.

It makes no sense to lend recklessly to those who cannot afford it. Yet this suggests that the economy will not become buoyant again without a redistribution of income towards spenders or the emergence of another source of demand. Unfortunately, it is not at all clear what the latter might be.

Government spending is constrained. Business investment is curbed by weak prospective growth of demand. It is also unlikely to be net exports: everybody else wants export-led growth, too.

American education has also deteriorated. It is the only high-income country whose 25-34-year-olds are no better educated then its 55-64-year-olds. This is partly because other countries have caught up on the US, which pioneered mass college education. It is also because children from poor backgrounds are handicapped in completing college.

The S&P report notes that for the poorest households college graduation rates increased by only about 4 percentage points between the generation born in the early 1960s and that born in the early 1980s. The graduation rate for the wealthiest households increased by almost 20 percentage points over the same period.

Yet, without a college degree, the chances of upward mobility are now quite limited. As a result, children of prosperous families are likely to stay well-off and children of poor families likely to remain poor.

This is not just a problem for those whose talents are not fulfilled. The failure to raise educational standards is also likely to impair the economy’s longer-term success.

Some of the returns to education may just be the reward to obtaining a positional good: the educated do better because they have won a zero-sum race. Yet a better educated population would also raise everybody to a higher level of prosperity.

The costs to society of rising inequality go further. To my mind, the greatest costs are the erosion of the republican ideal of shared citizenship.

As the US Supreme Court seeks to bend the constitution to the will of plutocrats, the peril is to the politically egalitarian premises of the republic. Enormous divergences in wealth and power have hollowed out republics before now. They could well do so in our age.

Yet even for those who do not share such concerns, the economic costs should matter. The “secular stagnation” in demand, to which Lawrence Summers, the former US Treasury secretary, has referred, is related to shifts in the distribution of income.

Equally, the transmission of educational disadvantages across the generations is also a growing handicap to the economy. A debt-addicted economy with stagnant levels of education is likely to fare ill in future.

— Financial Times